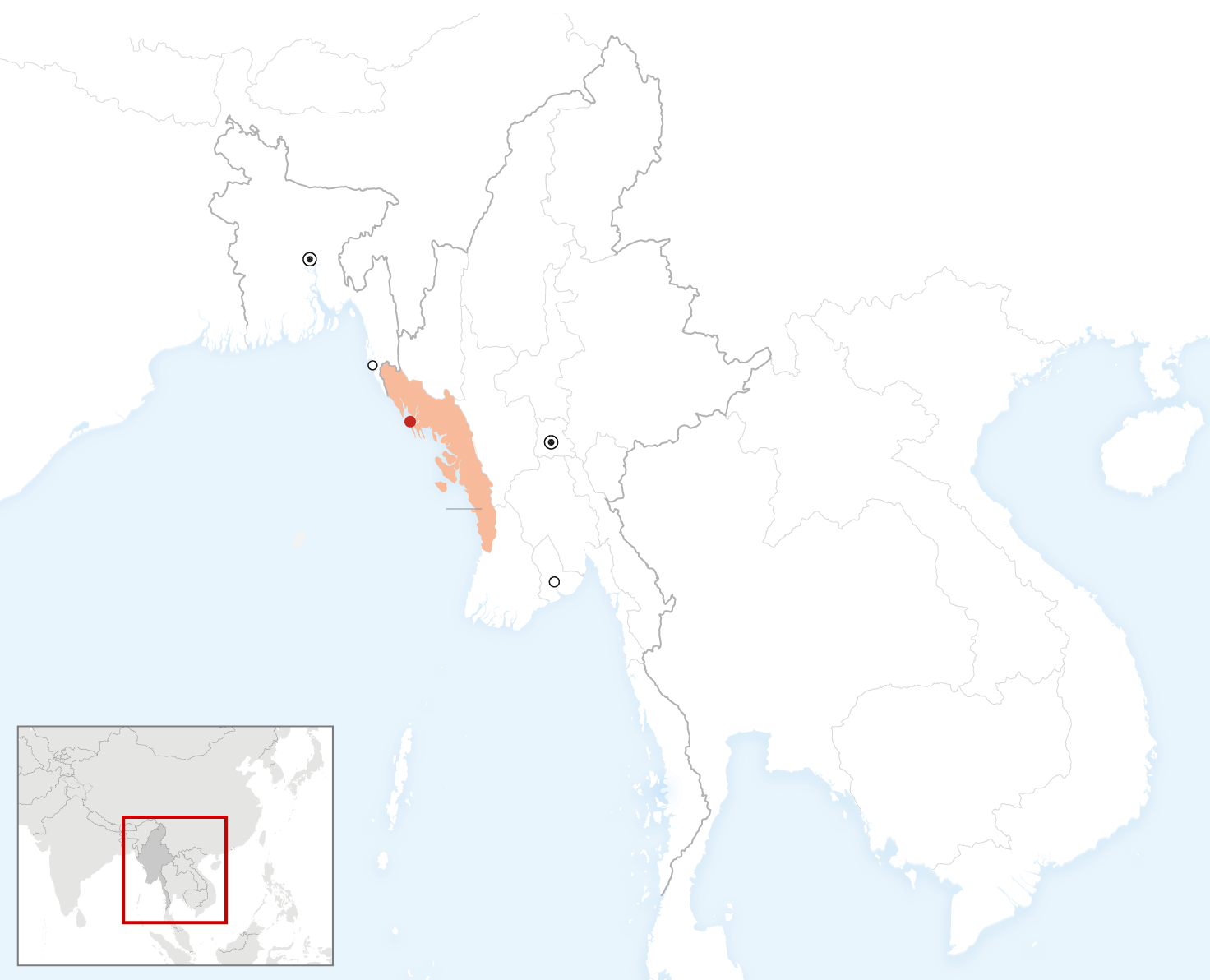

In the midst of escalating violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine State, the military junta is facing grave accusations of using hunger as a strategic weapon against civilians. As hostilities between the junta and the Arakan Army (AA) continue to intensify, tens of thousands of civilians find themselves trapped in a humanitarian nightmare, struggling to survive amid increasingly desperate conditions.

The Human Toll: Stories from the Frontlines

One of the many victims of this crisis is Khin Mar Cho, a 38-year-old mother from Byine Phyu village. Her life was shattered when soldiers stormed her village, indiscriminately firing upon residents. Her brother was among those killed, and she narrowly escaped with her two young children. They fled to a monastery near Sittwe, the regional capital, where they now live with 300 other displaced villagers. The monastery, which once served as a place of worship, has been transformed into a makeshift displacement camp. Food and medicine are scarce, and the monk who oversees the camp is struggling to provide even the most basic necessities.

Khin Mar Cho’s story is just one of many in a region where the junta’s tactics have plunged the population into crisis. The military’s strategy includes setting up roadblocks, closing waterways, and refusing to issue access permits to humanitarian organizations, effectively cutting off food supplies to entire communities. These actions appear to be part of a broader effort to starve out the Arakan Army and the communities that may support them.

The Scale of the Crisis: Blockades and Skyrocketing Prices

Rakhine State, which has long been one of the poorest regions in Myanmar, is now facing an unprecedented food crisis. According to the United Nations, 873,000 people in Rakhine are in need of food assistance, but less than 25% have received any aid since the conflict reignited in November 2023. The junta’s blockade has made it nearly impossible for aid groups to reach those in need. Key supply routes from Yangon and other major cities have been sealed off, driving the prices of food and other essential goods to levels far beyond what most people can afford.

In the town of Mrauk-U, a historic city that has seen intense fighting, the situation is dire. Residents report that rice, the staple food, has become a luxury item. A sack of rice that once cost 40,000 kyats now sells for more than 150,000 kyats, and even at these prices, supplies are limited. With farming activities disrupted by the conflict, local rice production is expected to fall by more than 50% this year. Many farmers have been forced to abandon their fields, either because they have been displaced by the fighting or because they fear being caught in the crossfire.

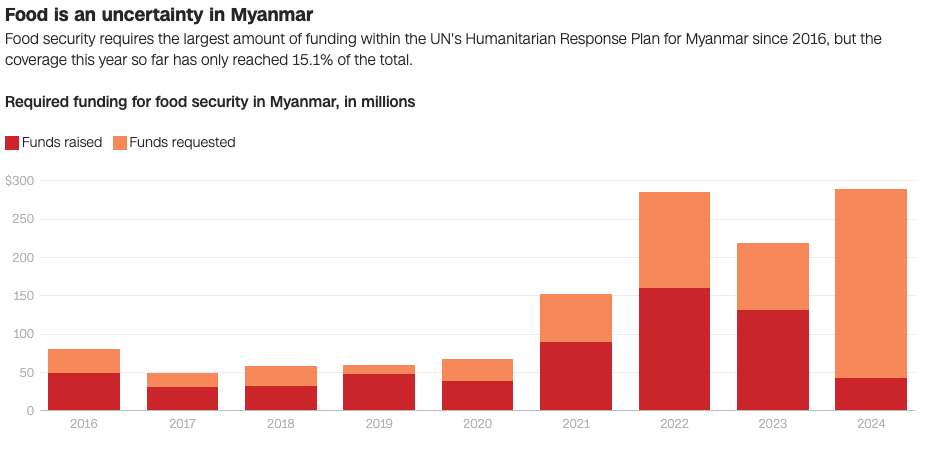

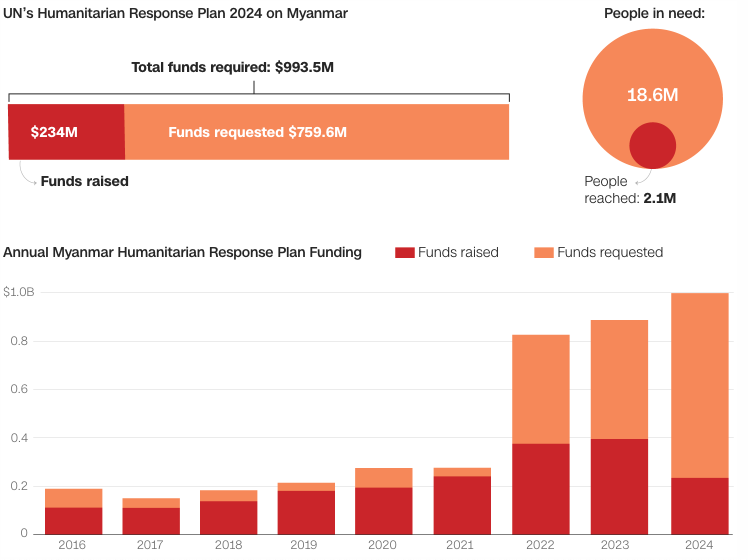

Source: Finance Tracking Services, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian AffairsGraphic: Rosa de Acosta, CNN

Lives in the Balance: The Struggle for Survival

Among those hardest hit are the Rohingya, a Muslim minority group that has long been persecuted in Myanmar. In towns like Buthidaung and Maungdaw, near the Bangladesh border, the Rohingya are facing starvation. Many have been displaced multiple times, and their access to food has been severely curtailed by the junta’s blockade. For people like Jamila, a 27-year-old mother of three, survival has become a daily battle. After fleeing her village, she and her children spent two weeks hiding in the jungle, surviving on little more than banana leaves and muddy water from a nearby pond. They eventually made it to a camp in Sittwe, but the conditions there are scarcely better. The camp is overcrowded, and the little food that is available is rationed to the point where it barely sustains life.

Mohammed, a 43-year-old father of four, has lived in a camp in Sittwe since 2012, when anti-Muslim violence first swept through Rakhine State. He describes the heart-wrenching experience of having to look into his children’s eyes and tell them there will be no dinner tonight. With the junta’s blockade cutting off the camp from nearly all outside support, even basic necessities like cooking oil and salt have become prohibitively expensive. What little food remains is being sold at prices far beyond the reach of most camp residents.

Source: Finance Tracking Services, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Graphic: Rosa de Acosta, CNN

Accusations of War Crimes: International Outcry

Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and other human rights organizations have condemned the junta’s actions as war crimes. By deliberately blocking food aid and using hunger as a weapon against civilians, the junta is accused of violating international humanitarian law. These organizations have called for urgent international intervention to prevent a full-blown famine in Rakhine. However, efforts to raise the alarm have been hampered by the junta’s tight control over information and access to the region.

The international community has so far been slow to respond. The United Nations’ humanitarian response program for Myanmar is one of the most underfunded in the world, with only 20% of the necessary funds raised. Aid officials warn that without an immediate and significant increase in funding, millions of people could be left to starve.

The Plight of the Displaced: A Monastery on the Brink

At the monastery where Khin Mar Cho and her family have taken refuge, conditions continue to deteriorate. The monk who runs the camp has managed to secure a few donations from local supporters, but these are nowhere near enough to meet the needs of the 300 people now sheltering there. Disease is spreading rapidly among the camp’s residents, many of whom are weakened by hunger. The camp’s only consistent visitors are from the local fire service, who come not to deliver aid, but to help bury those who do not survive.

As the conflict in Rakhine drags on with no end in sight, the situation for civilians continues to worsen. For those like Khin Mar Cho, who have already lost so much, the future remains uncertain. They can only hope that the world will take notice of their plight before it is too late.