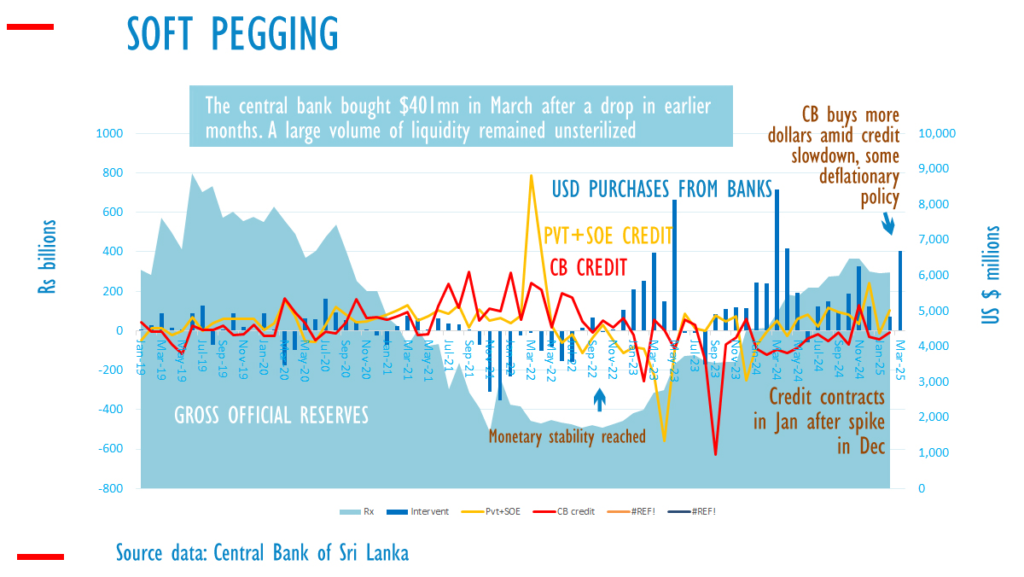

Sri Lanka’s Central Bank purchased $401.9 million from commercial banks in March 2025, marking a recovery after relatively weak foreign exchange purchases in the first two months of the year, according to official data.

In total, the Central Bank has acquired $484 million during the first quarter of 2025. Under the terms of the country’s ongoing agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Sri Lanka is expected to accumulate around $200 million per month in foreign exchange—approximately $2.5 billion annually. These funds are intended for reserve building and the repayment of external debt and interest.

To achieve these targets, the Central Bank is required to pursue deflationary monetary policies. Unlike Treasury operations, Central Bank dollar purchases result in the creation of new money, which can exert pressure on domestic interest rates and fuel credit growth. If this newly created liquidity is not absorbed or “sterilized,” it can lead to a drop in short-term interest rates. The increased liquidity would then fuel bank lending, placing further strain on the foreign exchange market and potentially causing reserve losses or currency depreciation unless the exchange rate is actively defended.

In late 2024, the Central Bank had printed money to suppress overnight interest rates, which led to some depletion of reserves. However, since then, overnight rates have stabilized around 8.00 percent, the Central Bank’s current single policy rate. This rate is slightly above the official floor rate, though a significant volume of excess liquidity remains unsterilized.

As of April, much of this liquidity may begin to circulate with the increased cash demand during the traditional New Year festival season.

Despite current signals of monetary tightening, economic analysts caution that maintaining a single policy rate alongside excess reserve levels could destabilize Sri Lanka’s IMF program. They note this approach mirrors the monetary policy missteps between 2015 and 2019, which contributed to economic instability and increased the risk of sovereign default.

If the Central Bank fails to manage inflationary pressures or loses control of reserve accumulation, the country may be pushed closer to a second default, analysts warn.