he alleged sexual assault of a doctor at the Anuradhapura Teaching Hospital has not only raised concerns about gender-based violence but has also ignited a wider debate on press freedom and ethical reporting in Sri Lanka.

Despite the incident being reported over two months ago, media outlets have refrained from disclosing the doctor’s personal details—including her name, appearance, ethnicity, religion, or family background. However, controversy arose when the Anuradhapura police summoned senior court journalist Upali Ananda to question how he obtained the B report filed in court regarding the case.

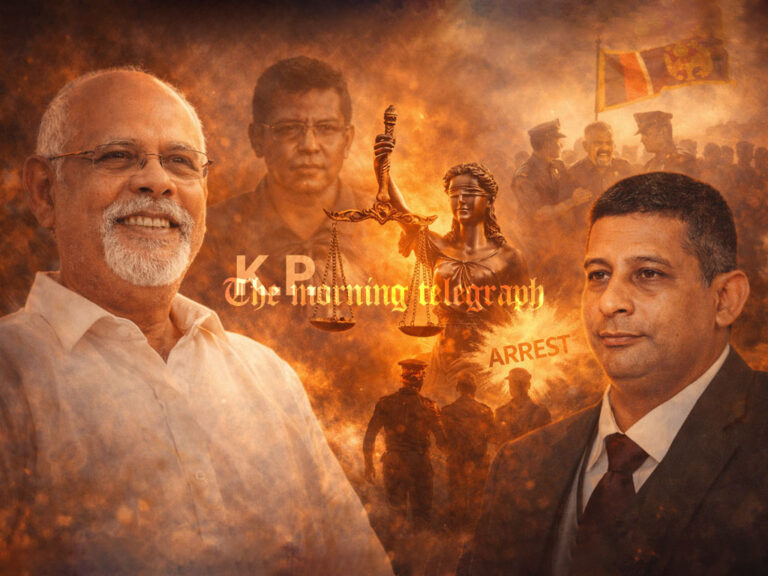

A Journalist With Two Decades of Experience Questioned

Upali Ananda, a seasoned court reporter with nearly 20 years of experience covering cases in courts across Polonnaruwa, Kurunegala, Matale, Kandy, and Anuradhapura, was called to the police station in connection with his reporting on the case.

The Free Media Movement (FMM) condemned the police’s action, calling it a troubling infringement on journalistic freedom. FMM convener Lasantha de Silva said the police’s behavior raises concerns and, in this case, has backfired on them.

He cited other incidents—such as the wrongful handling of the Seya Sadewmi case, the public questioning of a woman at police headquarters, and a journalist’s sister being accused in a murder investigation—as examples of questionable police conduct.

‘Police Themselves Provide These Reports’

Lasantha de Silva emphasized that B reports are official documents submitted to court by the police, not material obtained unlawfully by the media. Therefore, questioning a journalist about how they accessed such information is misplaced.

He pointed out that if the victim had been from a marginal background—like a plantation worker—such scrutiny of the journalist might not have occurred. According to him, this inconsistency in treatment reveals systemic issues.

De Silva praised the journalist for responsibly reporting the incident without revealing the victim’s identity. He noted that the real issue lies in how media institutions sometimes dramatize stories, which can cause distress to victims.

Even if the public does not know who the doctor is, her friends and colleagues certainly do, he said, adding that repetitive media exposure could cause her further trauma and social pressure.

He stressed that while reporting on sexual violence is necessary to raise awareness, the primary responsibility lies with editorial teams to maintain ethical standards in such sensitive coverage.

Court Summons Police Over Journalist Interrogation

Following criticism of the police’s action, the Anuradhapura Magistrate’s Court has summoned the Chief Police Inspector of the Anuradhapura Headquarters to appear in court on May 7. The court will examine the legitimacy of questioning a journalist over his reporting of the case.

The order followed a motion submitted by Attorney-at-Law Anuruddha Wijayaratne, who appeared on behalf of journalist Upali Ananda. He argued that the police’s inquiry into how the journalist accessed the B report violated both constitutional guarantees of press freedom and the ethical code governing journalists.

The police had previously informed the court that the victim doctor had been emotionally distressed by a TV news segment aired on March 13, 2025, regarding the case. This claim was supported by a complaint lodged by the Anuradhapura branch of the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA).

According to the police, the case falls under two legal provisions: Section 3(1) of the Crime Victims Protection Act No. 10 of 2023, and Section 444 of the Criminal Procedure Code. However, Attorney Wijayaratne challenged this, arguing that these sections do not amount to a criminal offense and that the media report in question had not even been submitted to the court as evidence.

Confidentiality of Sources Protected by Law

Wijayaratne stressed that journalists are protected under a code of ethics approved by Parliament, which explicitly states that reporters are not required to reveal their sources unless those sources have authorized such disclosure.

He pointed out that unless the published report was false or incited public unrest, forcing a journalist to disclose a source is tantamount to suppressing press freedom.

He further stated that the B report did not reveal the victim’s name or place of residence—only her profession as a doctor. It is the responsibility of the police, he said, to investigate how the report was leaked, not to interrogate journalists.

The lawyer criticized the police for presenting a complaint to the court without submitting the allegedly harmful media report as evidence, and said that the judicial system must remain transparent and open—not act like a religious authority operating in secrecy.

A Justice Ministry circular also permits journalists to attend and report on court proceedings, reinforcing the principle of transparency in judicial affairs.

Journalist Defends His Actions

Journalist Upali Ananda confirmed that the police had asked him who had provided the details of the B report submitted to court.

“I told them that revealing that would violate the code of ethics for journalists, which I am obligated to follow under Article 4,” he said.

Ananda further clarified that there was no formal complaint from the assaulted doctor herself, nor from the local GMOA branch, regarding the media coverage.

Police Respond

When asked for comment, a senior police officer said the interrogation of the journalist was not an attack but a procedural step in an ongoing investigation. He added that the legal aspects of the matter are still being examined.