From late-night rum sessions on Sri Lanka’s fate to mentoring young diplomats who now lead missions worldwide, Lakshman Kadirgamar’s legacy blends political mastery with personal grace. His story is a lesson in defending sovereignty, building alliances, and inspiring loyalty that lasts decades.

Lakshman Kadirgamar rejected narrow ethnic identity with the now-famous words, “I am not a tribalist.” It was more than a statement; it was the central truth of a life spent defending a nation’s integrity while remaining open to the world.

I first knew him through my father, the journalist Mervyn de Silva. They met as university students and later reunited when Dr. Gamani Corea and Mervyn formed the Foreign Affairs Study Group (FASG) to help Sri Lanka recover from the diplomatic setbacks of the late 1980s. When President Premadasa sought their advice, Mervyn introduced his old friend Lakshman, fresh from his tenure at WIPO bringing him into the FASG. It was here that Kadirgamar made the leap from international law to the sharper, riskier stage of international politics.

When Mervyn died in 1999, Lakshman befriended me personally. He often invited me to his home for long nights of political talk over a prized bottle of Caribbean rum, dissecting the country’s war, the Norwegian-facilitated ceasefire between Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and Velupillai Prabhakaran, and the regional stakes involving India. He seemed to believe those overnight conversations mattered, perhaps because they allowed him to test ideas in a space free from protocol.

What set him apart was his ability to balance contradictions. He could champion devolution as a political solution to the Tamil question while standing firmly against separatism and excessive concessions to the LTTE. He was as committed to national sovereignty and territorial integrity as he was to human rights. When President Chandrika Kumaratunga’s 2000 draft constitution came before Parliament, he made an impassioned plea for its adoption, only to be let down by the TULF’s last-minute reversal.

His resistance to the dangers in Ranil Wickremesinghe’s 2002 ceasefire agreement—particularly its “line of control” dividing the island was equally resolute. He made a landmark parliamentary speech, then personally persuaded the Sunday press to publish it when the Foreign Ministry hesitated.

Lakshman’s foreign policy instincts were unmatched. He understood that true balancing between the US, China, and India meant engaging each power without letting any establish a permanent footprint on Sri Lankan soil. His friendships spanned from Colin Powell in Washington to senior figures in Beijing and New Delhi, yet he knew exactly where to draw the line.

This principle-driven diplomacy was paired with a personal touch that shaped the careers of a generation.

In 2001, I was a naval officer newly appointed as Defence Adviser to our High Commission in New Delhi. Before departure, I was summoned to meet the Minister at 9 a.m. at his residence. He first cleared his schedule for two junior clerical staff headed to Western embassies, then gave me not the allotted 30 minutes, but 90—probing my experiences, briefing me on India’s importance, and setting the tone for my posting. That meeting defined my approach for the next three years.

He visited New Delhi often, each trip turning our mission into a hive of preparation. His habit was to listen—really listen—to our views, even from the most junior officers. He introduced us to India’s top leaders, government and opposition alike, with the strategic understanding that today’s opponents could be tomorrow’s partners in power.

There were lessons in every gesture. When meeting his close friend, Indian Defence Minister Pranab Mukherjee, Kadirgamar broke protocol to greet him at his car, explaining simply, “There is no protocol for friends.” He tracked the progress of the Indian monsoon, knowing its agricultural outcomes shaped the region’s economic aid patterns. He saw beyond ceremony to the forces that truly moved nations.

And there was warmth. He could pause on the way to a meeting with the President and the Russian Foreign Minister just to straighten a junior diplomat’s tie, saying, “Now it looks better.” He made young officers feel seen and valued, a quality rare in high office.

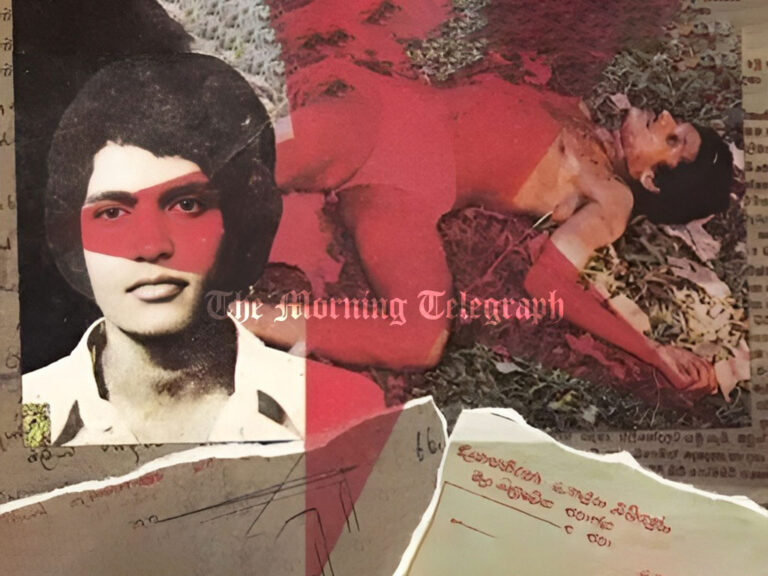

August 12, 2005, began with sports and camaraderie at Welisara Naval Base, but ended in grief. Around 9 p.m., his security officer called: “Sir, the Minister was shot. His body is at Colombo Mortuary.” The LTTE had claimed its most determined opponent.

I arrived to find his chest opened from the postmortem, one bullet having torn through the heart that had once carried the torch of independence at 16, representing Sri Lankan Tamils in the symbolic lighting of the Freedom Lamp. The same heart had powered him to rugby and cricket colours at Trinity College, the 110-metre hurdles title at the All-India University Games, and the Ryde Gold Medal for best all-round student. It had carried him through Oxford, where he became President of the Oxford Union, and through a distinguished legal career abroad before returning to serve Sri Lanka as Foreign Minister.

He worked tirelessly despite a kidney transplant, crafting speeches late into the night with his aide Lenagala. His words in New Delhi drew the praise of The Hindu’s editor N. Ram, who wrote, “When Lakshman speaks, India listens.” His wit shone in moments like his impromptu 2004 London address to Sri Lanka’s cricket team, skewering politicians with the same deftness he used to parry diplomatic barbs.

Kadirgamar’s doctrine, if we may call it that,was to defend the country’s sovereignty while being a friend to all; to build personal trust at the highest levels without giving away a single inch of national interest. He was neither the nativist ultra-nationalist nor the cosmopolitan supplicant of the West. He was a Sri Lankan first, last, and always.

His BBC interview with Zeinab Badawi remains a masterclass in national advocacy: rejecting tribalism without flinching on security and independence. Badawi herself told me she ended the interview convinced, becoming his friend thereafter.

Those he mentored now serve as ambassadors and high commissioners around the world, carrying forward his insistence on preparation, observation, and performance for the good of the country. We miss the Minister who not only defended our nation in global forums but also groomed those who would follow in his path. Had he lived, he would still be introducing us to world leaders as “my student.”

Lakshman Kadirgamar showed us it was possible to be principled without being rigid, friendly without being compromised, and visionary without losing touch with the ground beneath our feet. In these turbulent times, Sri Lanka would do well to rediscover the Kadirgamar doctrine and live by it.

Courtesy :- SRI LANKA GUARDIAN