For more than a decade, Sri Lanka’s controversial “Chichi rocket” – formally known as Supreme Sat has fueled political arguments, ridicule, and denial. While government ministers claim no such satellite exists, official United Nations records appear to tell a different story. At the center of the storm are disputed funds, political egos, and an orbiting piece of space hardware that refuses to vanish from the debate.

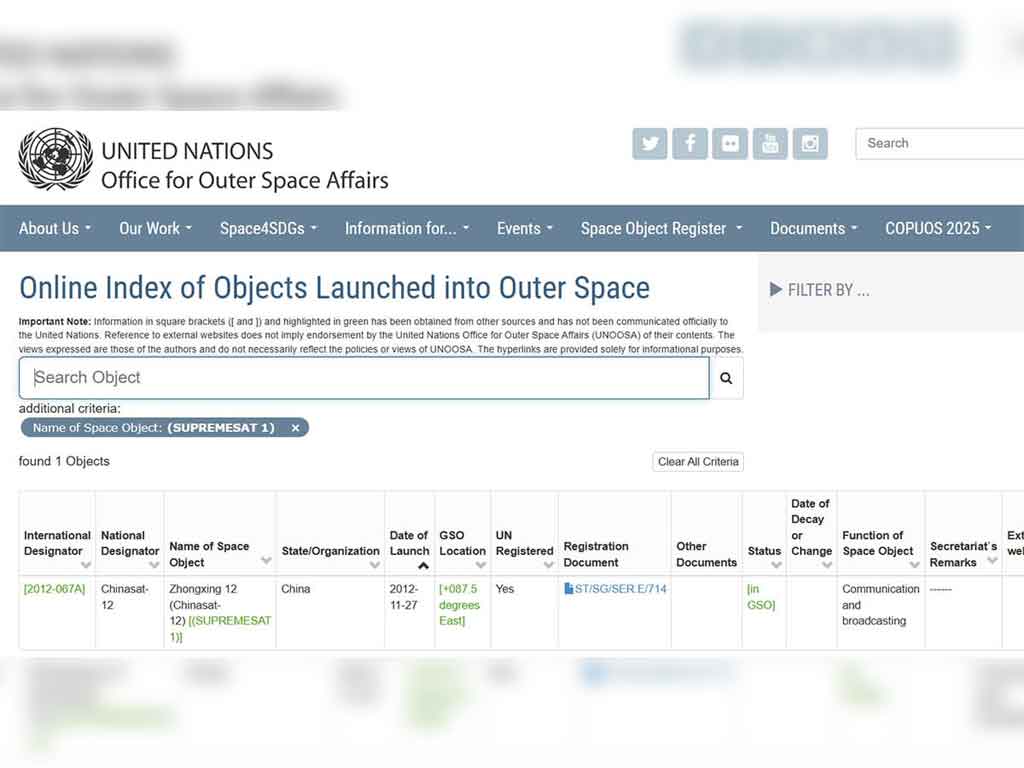

The United Nations (UN) has confirmed the registration of the so-called “Chichi rocket,” officially known as Supreme Sat, a satellite long dismissed by Sri Lankan government spokesmen as a phantom. According to Pivithuru Hela Urumaya leader, lawyer Udaya Gammanpila, the evidence lies in the UN’s own online records, exposing yet another contradiction in the government’s narrative.

Speaking at his party headquarters, Gammanpila noted that while the JVP leadership often dismisses celestial matters as irrelevant, the government cannot escape the fact that the Supreme Sat satellite has dealt it a severe political blow. Minister of State Media, Nalinda Jayatissa, recently told journalists that no satellite called Supreme Sat had ever been launched. Citing the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) as his authority, he claimed there was no such entry in the global space registry.

That assertion, Gammanpila countered, was not only misleading but technically false. The ITU is not the UN’s agency for satellites at all. Its role is largely confined to the regulation of universal frequencies and international telecommunications standards. The specialized body responsible for satellites is the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), created under international treaty. And when one turns to UNOOSA’s official register, the “phantom” satellite suddenly appears, alive and well in the record.

A simple online search, Gammanpila explained, reveals the “Online Index of Objects Launched into Outer Space.” Entering “Supreme Sat” produces two listings: Supreme Sat 1 and Supreme Sat 2. Contrary to government denials, these satellites are officially catalogued. “I’m not accusing anyone of lying out of thin air,” Gammanpila declared. “This is in the UN’s own database for the world to see.”

Further details confirm the dual identity of Supreme Sat 1. Its Chinese designation is Song Xing 12, while internationally it is known as Chinasat 12. Supreme Sat Company purchased communications payload capacity from this satellite, comparable to buying a single floor of a multi-storey building. Ownership, therefore, became a matter of shared branding. As such, the satellite carries both the Chinese and Sri Lankan flags and is simultaneously recognized as Supreme Sat 1 in co-branding terminology.

“This is not unusual,” Gammanpila explained. “Just as Nagadeepa in Sinhala is known as Nainativu in Tamil, a satellite can carry different names in different contexts. This one has three the Chinese name, the international designation, and the Sri Lankan branding all documented officially.”

The UN register lists the launch date as 27 November 2012, a milestone hailed by the then-government as Sri Lanka’s entry into the space age. The record also includes a registration document accessible in multiple languages, verifying its operational status. Importantly, the site provides continuous updates on whether a satellite remains active, has decayed into debris, or has been retired. Supreme Sat remains in active status, with no decay or removal date recorded.

Yet, despite this evidence, the government continues to shuffle its narrative. Minister Nalinda Jayatissa insists that Sri Lanka’s allocated orbital slots remain empty. Supreme Sat never claimed otherwise; nor did opposition critics. The controversy originated when Minister Wasantha Samarasinghe accused the Rajapaksa administration of handing over national orbital rights to Supreme Sat Company without a transparent bidding process. Nalinda, in turn, dismissed Samarasinghe’s allegation as fabrication.

The contradictions snowballed. Within a day of the Prime Minister’s assurances to Parliament, Minister Wasantha alleged the Prime Minister himself had lied. Days later, Nalinda countered that Wasantha had lied. Six days on, Gammanpila challenged Nalinda as the liar. The cycle of accusations has since become endless, eroding public confidence.

Quoting an English proverb, Gammanpila said: “If you can’t convince, then confuse.” That, he argued, was precisely what the government was doing – flooding the public with half-truths and denials rather than addressing the central question.

The heart of the issue is not whether Supreme Sat Company makes profits or losses, nor whether Sri Lanka’s orbital rights remain unused. The fundamental question is whether the country’s space dream was financed with $280 million of national funds or $380 million of the Rajapaksa family’s private wealth. The Prime Minister has since insisted that no taxpayer money was spent. On this specific point, no one in the opposition has openly contradicted him.

For Gammanpila, the rest is mere noise. “The Supreme Sat remains in orbit. The UN records confirm it. The government, meanwhile, is stuck in a cycle of contradictions. If they think I’m lying, I challenge them to prove it. Until then, the truth is simple: the so-called Chichi rocket is no myth, but a documented fact.”