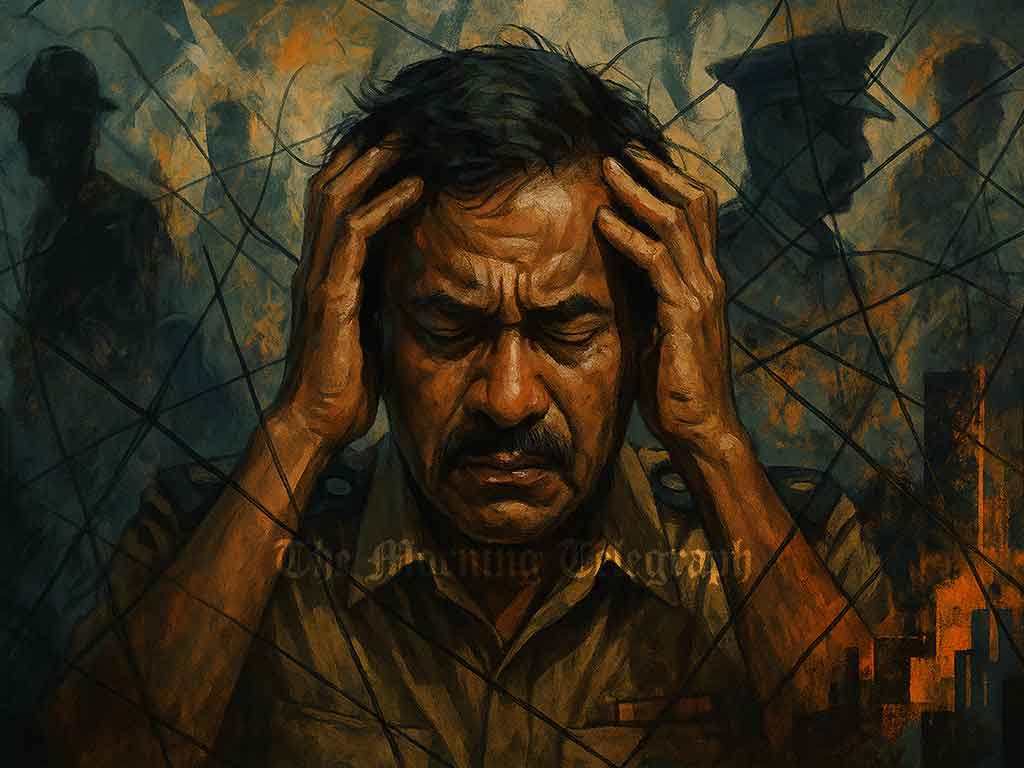

This story reveals a harsh truth rarely spoken aloud: officers of Sri Lanka’s State Intelligence Service (SIS), though drawn from the ranks of the Police Department, are deprived of the authority, tools, and resources required to act in crises. Stripped of operational powers yet burdened with impossible expectations, they are held accountable for failures they cannot control.

On 17 July 2025, the National Police Commission (NPC) stunned the world by dismissing Nilantha Jayawardena, Sri Lanka’s most senior police officer at the time, who served as Director of the SIS during the Easter Sunday attacks of 21 April 2019. His dismissal was justified on grounds of dereliction, an alleged failure to prevent the massacre. For the first time in history, an intelligence officer was condemned not for concealing information, but for failing to act after repeatedly alerting defense authorities, even in the final hour before the blasts.

This decision shattered precedent. It represents perhaps the gravest violation of fundamental rights committed against a senior public servant in Sri Lanka since independence in 1948. By making Jayawardena the scapegoat, the NPC exposed the country’s ignorance, shortsightedness, and bureaucratic mediocrity. Instead of recognizing structural failures, leaders punished the one man who had done his duty.

The central truth is simple: SIS officers do not wield police powers. Despite holding police ranks, once seconded to intelligence service they lose operational authority. They are neither equipped nor trained for preventive action. Their role is intelligence collection and analysis, not raids, arrests, or armed intervention.

The Anatomy of Sri Lanka’s Intelligence Community

By international definition, an intelligence community is a federation of specialized agencies that collaborate to safeguard national security and conduct foreign intelligence. In Sri Lanka, five main agencies form this network:

- State Intelligence Service (SIS)

- Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI)

- Directorate of Naval Intelligence (DNI)

- Directorate of Air Force Intelligence (DAFI)

- Special Branch of the Police Department (SB)

Of these, the SIS—previously the National Intelligence Bureau (NIB), is Sri Lanka’s primary civilian intelligence body. It handles both domestic and foreign intelligence under the direct authority of the Ministry of Defence, reporting straight to the Secretary of Defence.

Until 1984, intelligence work fell to the Police, first through the Special Branch and later the Intelligence Services Division. But the devastating 1983 riots revealed crippling weaknesses. In response, President J.R. Jayewardene’s government created the National Intelligence Bureau, pooling resources from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Police. Two decades later, in 2006, it was restructured into the SIS.

The SIS’s duties are broad yet clearly defined:

- Collect and analyze intelligence relating to national security.

- Conduct covert surveillance and undercover investigations.

- Vet candidates for sensitive institutions, from armed forces to police.

- Prepare threat assessments for VIP and government security.

- Train other institutions in intelligence practices.

- Manage foreign intelligence cooperation.

But note carefully: nowhere in these responsibilities does the SIS conduct armed operations or preventive strikes. Their mandate is advisory, not executive.

Chains of Command and Power Gaps

The Chief of National Intelligence (CNI) holds responsibility for coordinating these agencies. While SIS reports directly to the Secretary of Defence, the DMI, DNI, and DAFI report to the commanders of their respective forces, and the Special Branch reports to the Inspector General of Police.

Appointments follow political hierarchy: the Cabinet names the CNI, while the Secretary of Defence appoints the SIS Director. Critically, only the CNI sits on the National Security Council (NSC). The President convenes the NSC, where intelligence chiefs brief national leaders. In theory, this creates a coordinated security mechanism. In practice, it leaves gaps—especially when intelligence is ignored by those who wield actual operational authority.

Tradition dictates that SIS leadership has always been drawn from the Police. Exceptions are rare: a civilian Deputy Director in 1998, a retired Deputy Inspector General in the late 1990s, and a Major General appointed Director in 2019. Beyond these, all SIS directors and deputies have been police officers seconded from the department.

This arrangement creates a paradox: SIS officers carry police ranks yet serve under the Ministry of Defence, cut off from law enforcement powers. They may gather intelligence, but execution lies elsewhere, military units, police task forces, or special operations squads.

Shadows and Secrecy: The Reality of Covert Work

At its core, intelligence thrives on covert operations. Globally, such work is defined as secret activity designed to blend into the environment, impossible to trace back to its sponsor. For SIS officers, seconded from the police, this requires shedding their visible police identity.

They abandon uniforms, carry unique SIS-issued IDs, and live behind cover identities. To survive, some grow beards, wear earrings, or adopt bohemian appearances. Others masquerade as beggars. Many are housed in secret facilities, never setting foot in SIS headquarters. Firearms, if issued, are strictly for self-defense. Even if a crime occurs before their eyes, they are forbidden from intervening.

SIS relies heavily on Human Intelligence (HUMINT). Two key agent types drive their operations:

- Infiltration agents (plant agents)—inserted into target groups under false pretenses.

- Penetration agents (recruit agents)—individuals already inside who are turned into informants.

Infiltration, though riskier, is deemed far more reliable. An example from 1988 demonstrates this: a young sub-inspector, seconded to the NIB, infiltrated a southern subversive movement so successfully that he became a regional leader. When militants attempted to move hidden arms, he tipped off authorities. The operation was smashed, though the infiltrator himself vanished into a new identity for safety. His bravery underscores both the value and vulnerability of such officers.

The Fatal Misjudgment of the NPC

The NPC’s dismissal of Nilantha Jayawardena rests on a fundamental misunderstanding: SIS officers possess no police authority. They cannot order raids, make arrests, or mobilize armed units. Their mandate is to pass intelligence upwards. What happens or doesn’t happen afterward lies with the police, military, and government leadership.

The three-member committee that recommended Jayawardena’s dismissal revealed astonishing ignorance of intelligence mechanics. By scapegoating him, they punished the only official who had acted responsibly by providing timely warnings. His career, reputation, and retirement benefits were sacrificed to conceal the indifference of those who failed to act.

History is filled with miscarriages of justice. Alfred Dreyfus, falsely convicted of treason in France in 1894, spent years disgraced before eventual exoneration. In Sri Lanka, Henry Pedris, a decorated officer, was executed for treason in 1915 and pardoned only in 2024, 109 years too late. These cases illustrate a crucial truth: injustice can be corrected, even decades later, but only if societies confront their own mistakes.

Easter Sunday and the Impossible Burden

The Easter Sunday attacks stand as one of Sri Lanka’s darkest moments. Yet blaming the SIS Director for failing to stop them ignores reality. Intelligence officers did their job, they provided information to those empowered to act. It was the defense establishment and police leadership who failed to move.

Forcing SIS to bear responsibility is akin to punishing a meteorologist for a flood, while excusing the engineers who ignored the warning. By fining Jayawardena Rs. 75 million and branding him guilty, Sri Lanka not only wronged a dedicated officer but also undermined its entire security apparatus.

Would a retired officer, such as a DIG or Major General appointed as SIS Director have been found guilty too? If so, would courts demand that a retired man exercise authority he did not legally hold? The absurdity of the precedent speaks for itself.

The Global Perspective

Nowhere else in the world has an intelligence officer been criminally penalized for the failures of operational forces to act on intelligence. If an international panel were to review Sri Lanka’s Easter Sunday tragedy, the verdict would be damning: the SIS Director fulfilled his mandate; it was others who failed.

Such findings would not only exonerate Jayawardena but also expose Sri Lanka’s institutional ignorance. A state that cannot grasp the basic boundaries of its own intelligence services risks losing credibility globally.

A Call for Reason

The plight of Sri Lanka’s intelligence officers is not just about one man’s dismissal. It is about a system that demands miracles from those deliberately stripped of power. It is about officers risking their lives undercover, only to be abandoned when bureaucracy seeks a scapegoat.

The Easter Sunday case must serve as a turning point. Decisions based on misunderstanding must be revisited. Justice delayed may be justice denied, but it is never too late to right a wrong.

In reality, SIS officers cannot enforce law and order. They cannot storm safehouses, arrest terrorists, or prevent attacks. Their duty is to inform, and they did. Punishing them for failing to act is not only unjust, it is suicidal for national security.

Unless Sri Lanka acknowledges this truth, intelligence officers will continue to work in the shadows, not only against threats to the nation but against the betrayal of the very system they serve.

SOURCE :- SRI LANKA GUARDIAN