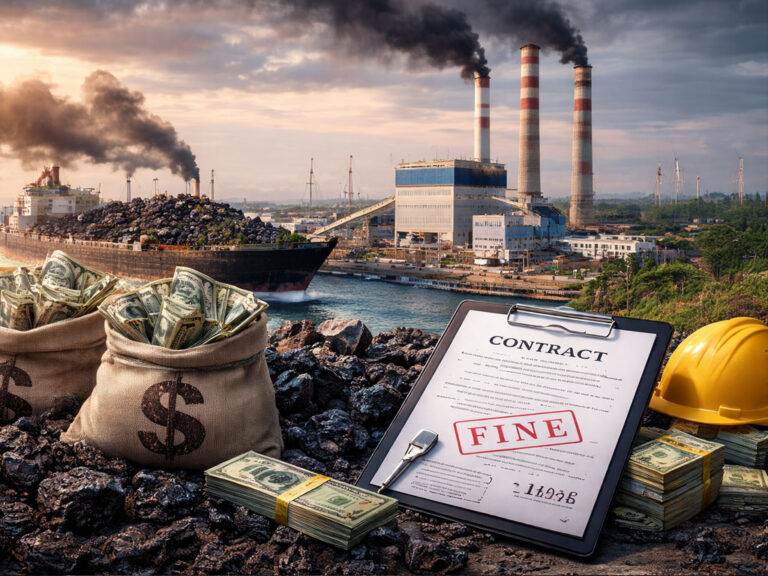

Sri Lanka’s latest coal import tender has ignited a storm of corruption allegations, with critics accusing the government of rewriting procurement rules to benefit a company tied to fraud, money laundering, and even cricket match-fixing scandals.

Sri Lanka’s power sector has been thrown into controversy after a coal import tender allegedly bypassed standard procurement rules and was awarded to a company accused of multiple corruption scandals. The Frontline Socialist Party (FSP) revealed shocking details at its seminar “Uttaraya Api” held in Polonnaruwa, warning that the entire process reeks of fraud.

According to FSP Education Secretary Pubudu Jayagoda, the tender for coal supply, opened on September 15, was awarded to Trident Chemphar, the lowest bidder. However, Jayagoda argued that the procurement guidelines had been deliberately altered to allow the company’s eligibility.

In the 2021 Sri Lanka Coal Registration Document, companies required a minimum coal reserve of 1,000,000 metric tons with a GCV of 5900 kCal/kg to qualify. Shockingly, the 2025 registration document slashed this requirement by 90% to just 100,000 metric tons, enabling Trident Chemphar to qualify. Jayagoda described this as “highly suspicious” and a calculated attempt to bend the rules.

The company itself carries a dark history of corruption allegations. In the 2016 Auditor General’s report, Trident Chemphar was accused of violating government procurement guidelines when supplying 30,000 metric tons of rice to Sathosa in 2014. More recently, Sarath Chandra Reddy, one of its owners, was arrested in New Delhi in 2022 for money laundering linked to an excise duty scam.

Adding to the controversy, Sarath Bandara Jayasundara, Trident Chemphar’s local representative, is no stranger to scandal either. Once a cricket talent analyst, he was banned by the International Cricket Council (ICC) in 2019 for seven years on match-fixing charges.

Jayagoda argued that this coal deal is proof of Sri Lanka’s deep-rooted corruption network, which thrives through collusion between politicians, high-ranking officials, and racketeering businessmen. He claimed that while politicians are often the public scapegoats, the larger network continues to function unchecked.

The controversy also highlights government double standards. When Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) workers protested privatization, the President declared electricity an essential service. Yet when the coal tender was delayed for months, jeopardizing power supply, the urgency was ignored. Similarly, while rooftop solar producers were discouraged and tariffs were raised to unbearable levels, the government failed to enforce strict coal procurement safeguards.

Jayagoda warned that this scandal alone is enough to question whose interests the government truly represents. “Electricity supply was treated as essential when suppressing workers, but when corruption entered the coal tender, that principle vanished,” he said.

The coal tender fraud exposes not only the flaws in procurement but also a larger culture of systemic corruption. With the energy sector critical to Sri Lanka’s fragile economy, such allegations raise serious concerns about governance, accountability, and the future of sustainable power generation in the country.