A complaint filed with the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) over alleged defamation against Minister Wasantha Samarasinghe and his staff has triggered alarm bells about whether Sri Lanka is quietly reviving criminal defamation through indirect means, risking freedom of speech and undermining democratic accountability.

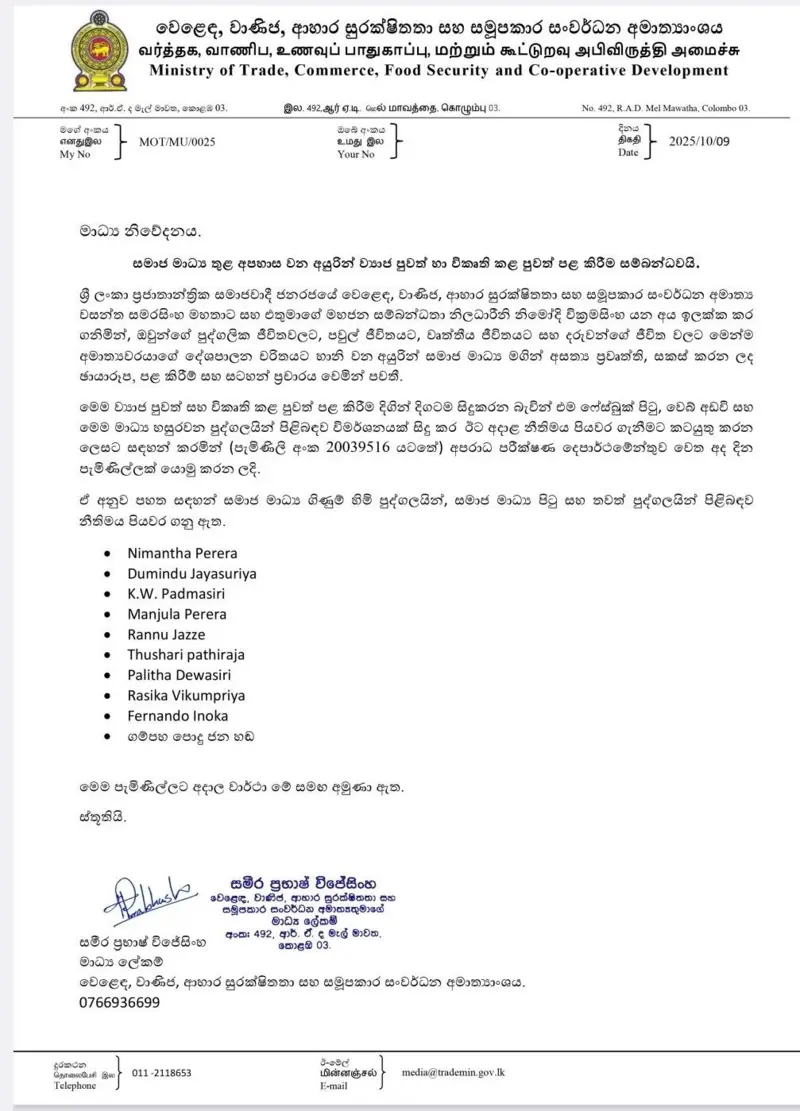

On October 9, a letter signed by the Media Secretary of the Ministry of Trade, Commerce, Food Security and Cooperative Development revealed that a complaint had been lodged with the CID regarding propaganda allegedly spread on social media. The complaint targeted content said to be damaging to Minister Wasantha Samarasinghe and his Public Relations Officer Nimodhi Wickramasinghe. It alleged that false news, fabricated photographs, posts, and notes were circulating online in ways that harmed their personal lives, family lives, professional reputations, and even the lives of their children, while also tarnishing the Minister’s political image. The ministry’s decision to escalate the matter to the CID marks yet another case where state resources are drawn into what critics argue should be private disputes.

The letter indicated that legal action would be taken against several social media accounts mentioned in the complaint. This pattern is not new. Since the National People’s Power (NPP) Party came to power, ministers and MPs have frequently gone before the CID to pursue alleged defamation cases. Among those who have done so are MP Nilanthi Kottahachchi, Deputy Minister of Mass Media Dr. Kaushalya Ariyaratne, and others. For many observers, this trend raises red flags about whether the ruling coalition is normalizing the use of state institutions to stifle dissent and criticism under the guise of protecting reputations.

The best thing is not to involve the state in this

Lasantha de Silva, convener of the Free Media Movement, warned that this growing practice indirectly undermines freedom of speech and expression. He explained that Sri Lanka abolished criminal defamation laws years ago, acknowledging that such statutes were incompatible with democratic practice. Yet politicians now routinely file complaints with the CID when facing criticism online, effectively reintroducing criminal consequences through the back door. Lasantha argued that such complaints act as an indirect threat: by signaling that critical speech could trigger police investigations, they chill the willingness of citizens and journalists to speak freely.

He noted that insults and slander have long been part of Sri Lanka’s political culture, where adversaries routinely attack each other’s character. Politicians, he suggested, must develop resilience to withstand such rhetoric rather than weaponizing state power to silence it. While he emphasized that defamation and falsehoods should never be condoned, he insisted that democratic societies handle such disputes through civil defamation suits in district courts. Resorting to state law enforcement, in his view, not only risks intimidation but also erodes the hard-won protections against criminal defamation.

The question is whether they are trying to bring in a criminal defamation law again

The warnings were echoed by Tharindu Jayawardena, chairman of the Young Journalists’ Association, who argued that using ministry-level announcements and CID complaints for personal insults constitutes an abuse of state property and power. He pointed out that when an individual politician is allegedly insulted, it does not equate to the ministry itself being attacked. By filing complaints at the institutional level, politicians are effectively shielding themselves behind government offices and using state resources for personal battles. Jayawardena described this as a misuse of the CID’s mandate, which was never designed to adjudicate questions of personal defamation.

He stressed that ministers already have sufficient legal avenues available. If they feel insulted, they can personally file civil defamation suits in district courts. Attempting to elevate such disputes into criminal matters, however, risks creating a dangerous precedent. He further linked the issue to Sri Lanka’s controversial Online Safety Act, which was itself criticized for creating excessive state powers over online speech. Even though the NPP opposed the Act during its introduction, the steady stream of CID complaints now risks achieving the same chilling effect it warned against.

The deeper concern, Jayawardena noted, is that repeated CID involvement in alleged defamation cases could signal an attempt to reintroduce criminal defamation laws in practice, if not in name. The pattern raises troubling questions: is this about protecting politicians from falsehoods, or is it about intimidating citizens, journalists, and activists into silence? He cautioned that even if no formal law has been reintroduced, the repeated use of the CID sends a message that criticism could result in police harassment. That, he said, is nothing short of an obstruction of free expression and an abuse of power.

Minister Wasantha’s response

The Minister himself offered little clarity. Wasantha Samarasinghe directed inquiries back to his media secretary, refusing to comment directly. His media secretary indicated that a response would be provided later, but none was received by the time of publication. This silence only fuels suspicion that ministers prefer to pursue critics through state institutions rather than engage openly with the public or defend themselves transparently.

What to do if you are insulted?

Legal experts argue that civil remedies remain the appropriate response to defamation. Lawyer Dinusha Lakmali explained that individuals who feel insulted can file civil contempt cases in district courts, where they can seek apologies or compensation for demonstrable harm. Civil procedures, while slower due to court delays, provide an avenue that respects free speech while addressing genuine grievances. She further noted that defendants in such cases enjoy key protections: if they can prove that their statements were true, made for the public good, or not intended as defamation, courts will consider these as valid defenses. These safeguards reflect a balance between protecting reputation and preserving free expression.

The bigger picture: Free speech at a crossroads

The risk of relying on the CID, however, is that such protections may be bypassed. Police investigations can themselves become punitive, regardless of whether charges hold up in court. The mere act of being summoned, interrogated, or placed under scrutiny creates a climate of fear. In a digital era where social media has become the primary forum for political debate, this chilling effect can severely limit democratic discourse. The fear is not abstract; it has historical roots. Sri Lanka’s criminal defamation laws, before being abolished, were repeatedly weaponized by governments to punish critical journalists and suppress opposition. Critics now fear that this dark chapter may be returning in disguised form.

The issue also highlights the blurred line between public accountability and personal insult. In democratic systems, politicians are expected to tolerate higher levels of scrutiny and criticism than private citizens. Their decisions and behavior, as custodians of public trust, are inherently subject to commentary. Attempting to insulate themselves from criticism through criminal investigation undermines this principle and shifts the balance dangerously in favor of political elites. The broader implication is that ordinary citizens may hesitate to challenge corruption, expose malpractice, or even express dissatisfaction, fearing legal reprisals.

This moment is therefore pivotal for Sri Lanka’s democratic trajectory. If the government continues to encourage or tolerate the use of the CID for personal defamation complaints, it risks sliding into authoritarian patterns where free speech is curtailed under the guise of law and order. The risk is not only domestic. International observers, including human rights organizations and foreign investors, closely monitor such developments as indicators of democratic health. A shrinking space for free speech undermines the country’s credibility on the global stage and can have far-reaching economic and diplomatic consequences.

The government’s defenders might argue that ministers have a right to protect their reputations, and that social media falsehoods can cause real harm to families and public figures. Yet this argument must be weighed against the fundamental democratic principle that free speech—even when harsh, satirical, or uncomfortable—remains essential for accountability. Civil remedies already exist for genuine cases of defamation, and these should be the primary recourse. Resorting to criminal investigations, by contrast, risks overreach, abuse of power, and a chilling effect on dissent.

The controversy surrounding Wasantha Samarasinghe’s case is emblematic of a larger battle over the boundaries of free expression in Sri Lanka. It illustrates how fragile the country’s progress remains and how easily old authoritarian habits can resurface under new guises. The responsibility now falls on civil society, the media, and independent institutions to resist the normalization of CID complaints as a response to political criticism.

As this debate unfolds, one thing is clear: Sri Lanka stands at a crossroads. It can either reaffirm its commitment to free speech and democratic accountability by discouraging the misuse of state institutions for personal battles, or it can drift back toward an era where the threat of criminal defamation silences critics and undermines the public’s right to speak truth to power.