Sri Lanka’s new administration stands at a decisive fork, squeezed by debt timelines, investor skepticism, diplomatic missteps, religious vetoes at home, and the unforgiving arithmetic of the IMF. The next twelve months will determine whether Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s government delivers credible reform or repeats the failures that led to bankruptcy just three years ago.

A Nation Back on the Edge

Sri Lanka’s political economy has entered a dangerous inflection point. Rhetoric and revolutionary slogans are no longer enough. A string of recent events has highlighted how exposed the island remains: delays in clarifying the government’s stance at the UN Human Rights Council, the shift from cheap Japanese financing to costly Chinese loans, retreats on LGBTQI and penal code reforms under religious pressure, looming electricity tariff hikes demanded by the IMF, and paralysis over provincial council elections.

Even the justice system has been shaken by a viral courtroom confrontation, symbolising the wider decay of rule of law. Together, these episodes reveal not isolated blunders but systemic weaknesses that could derail recovery.

For AKD’s government, the path forward is clear but treacherous: confront entrenched interests, impose economic discipline, and win back credibility abroad while stabilising confidence at home. Anything less risks returning Sri Lanka to the chaos of 2022.

The Debt Clock is Ticking

The biggest shadow is 2028, when Sri Lanka faces a massive repayment wall. Markets are already watching. Foreign direct investment remains stuck below one percent of GDP, reserves are thin, and global rating agencies remain unconvinced by Colombo’s promises.

The decision to accept a Chinese loan at 3.5 percent interest instead of Japan’s concessional 0.18 percent was read by economists as a red flag. It suggested politics, not prudence, still guides borrowing. The result is predictable: higher interest costs, more pressure on the rupee, and growing investor reluctance.

This debt overhang has already become a credibility test. Investors want more than vague assurances—they expect a coherent funding narrative. That means a transparent project pipeline where every major undertaking is screened for export earnings or import substitution potential. It also requires a sovereign borrowing framework that caps floating-rate exposure and prioritises concessional sources. A quarterly dashboard with reserves, FDI inflows, tax collections, and project milestones would give markets confidence that discipline is real.

Ambiguity is punished more harshly than bad news. By publishing consistent, audited data, Sri Lanka could narrow spreads and attract investment. Without such disclosure, scepticism will continue to dominate.

Power, Prices, and Political Pain

Electricity reform is the most immediate test. The IMF insists Sri Lanka must implement cost-reflective tariffs and restructure the Ceylon Electricity Board into four entities covering generation, transmission, distribution, and system operations.

The politics are brutal. Price hikes are deeply unpopular. Yet every delay compounds losses and forces taxpayers to subsidise inefficiency. Without reform, the CEB’s mounting debt could ignite another fiscal crisis.

A credible path requires three steps. First, introduce a multi-year tariff schedule with protections for low-usage households to soften the social blow. Second, empower a regulator with genuine teeth to publish quarterly loss data and enforce accountability. Third, launch a procurement reset to cut inflated contracts and standardise renewable energy auctions.

If implemented transparently, these steps could both cushion households and stabilise the utility. Avoiding them, however, all but guarantees rolling financial blackouts that choke growth and public trust.

Diplomacy on the Defensive

In Geneva, Sri Lanka’s foreign minister claimed victory because a resolution passed without a vote. The statement was widely mocked as self-delusion. In international diplomacy, irrelevance is not triumph. To investors and multilateral partners, it signaled drift and weakness.

If AKD’s government wants credibility, it must practice diplomacy that defends rather than deflects. That means publishing a narrow but verifiable rights and reconciliation plan with dates, agencies, and measurable deliverables. It also means adopting transparent settlement frameworks for disputes such as canceled foreign projects, to avoid the perception of arbitrariness.

International partners view consistency as strength. If Colombo continues with symbolic theatre abroad while offering little substance at home, Sri Lanka risks marginalisation at a moment when external capital and goodwill are desperately needed.

Social Reform Meets Religious Veto

At home, the government’s retreat from penal code reforms and LGBTQI tourism promotion exposed another fault line. Religious leaders forced the administration to back down, raising questions about whether policy is set by Parliament or pulpit.

Investors are less concerned about ideology than predictability. Families care about fairness and security. Both constituencies lose confidence when governments appear to legislate by veto.

The way forward lies in principled minimalism. Draft narrow legal reforms that target specific abuses, such as child protection, while avoiding moral panic. On tourism, market Sri Lanka’s brand around culture, wellness, and safety while applying quiet non-discrimination in service delivery. This combination preserves social peace while avoiding the reputational risks of exclusion.

The Democratic Gap

Provincial councils have been dissolved for years, and elections remain stalled because of legal and delimitation disputes. The JVP, once the fiercest critic of the system, now pushes for abolition altogether.

Yet the absence of subnational legitimacy risks long-term instability. Investors, citizens, and international partners all prefer governance structures that are predictable and accountable. Local administration is critical for land permits, service delivery, and disaster management.

The government must make a time-bound decision: either fix the law and hold elections, or abolish councils through constitutional change while introducing an alternative devolution framework. Drifting in uncertainty is the worst option, eroding both domestic trust and international credibility.

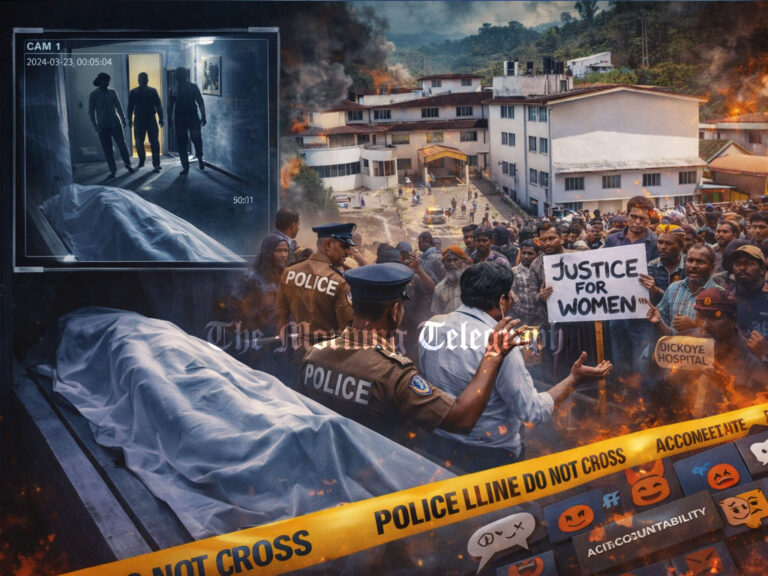

Rule of Law as an Economic Variable

The Mount Lavinia scandal, where a lawyer abused a police officer and appeared untouchable, shook public faith in justice. Social media outrage forced authorities to act, but the damage to credibility was already done.

Rule of law is not just an ethical principle. It is an economic variable. Without it, tax compliance collapses, contracts lose meaning, and investors take flight. The government should treat this as an opportunity for systemic reform: enforce professional discipline codes, protect whistleblowers, and expand digital evidence collection through body cameras and chain-of-custody systems.

These measures cost far less than stimulus packages but generate compounding returns in trust. For both citizens and investors, faith in impartial law is the foundation of long-term stability.

Growth Beyond Roads

The obsession with highways remains a trap. Expressways may create ribbon-cutting opportunities but are not a growth strategy. What Sri Lanka needs is a five-year plan anchored in real export engines: renewable energy and grid technology, specialty agriculture and food processing, IT and AI-driven services, maritime logistics and ship repair, and high-value tourism.

Unlocking these requires enablers: deeper capital markets, regulatory simplification, and talent retention. Diaspora bonds with FX protections, digital one-stop shops for permits, and targeted residency incentives for global professionals could all build momentum.

Citizens deserve an honest message: growth will not come from flashy projects but from industries that earn foreign exchange and create sustainable jobs.

Communication as a Reform Tool

Reforms fail when governments talk at citizens instead of with them. AKD’s government must adopt a new communication cadence. Every reform should be explained with diagnosis, action plan, and household impact. Families should be able to calculate how bills will change and what relief they qualify for.

Monthly unscripted press clinics could help build trust, while third-party validation of milestones would reduce skepticism. Social consent is earned incrementally. When people see pain linked to measurable progress, they give governments time. When they see only pain, patience evaporates.

A One-Year Contract with the Nation

Rebuilding trust requires a tangible contract, not vague promises. Within one year, the government should deliver:

- A legal fix or replacement model for provincial councils.

- An energy restructuring decree with a tariff glide path.

- A published sovereign project pipeline with value-for-money tests.

- A borrowing rule capping floating rate exposure.

- A digitised customs system with export clearance guarantees.

- A rights and reconciliation matrix with verifiable steps.

- A fast-track investor dispute resolution system.

- A teacher-parent protocol clarifying discipline standards.

- A diaspora investment scheme with hedging protections.

- A rule-of-law package covering professional accountability and whistleblower protection.

Each item is measurable and specific. Together, they would tilt perception from drift to discipline.

The Choice Before AKD

The constraints are brutal. The debt clock will not slow. The IMF will not soften. Religious leaders will not cheer reforms. Geopolitics will not wait. But none of these realities justify paralysis.

Nations pivot when leaders exchange symbolism for systems, when they spend political capital on reforms that outlast them. AKD’s government now faces a stark choice: deliver a sequence of measurable reforms that convince skeptics, or preside over a rerun of 2022 under a different banner.

Urgency is not a curse but a gift—it forces prioritisation and rewards competence. The next year will decide whether Sri Lanka writes the preface to recovery or the obituary of another failed experiment.

The choice is disclosure over drift, institutions over improvisation, and people over projects. Reform is no longer what AKD says to supporters. It is what he delivers to doubters.