The Afghanistan–Pakistan frontier is not just a border but a century-old wound carved by empire. Each clash, each retaliatory strike, is a reenactment of an unresolved colonial legacy. This investigative feature exposes how the Durand Line continues to fuel war, mistrust, and political theater on both sides — and why peace remains impossible.

A Border Written in Empire

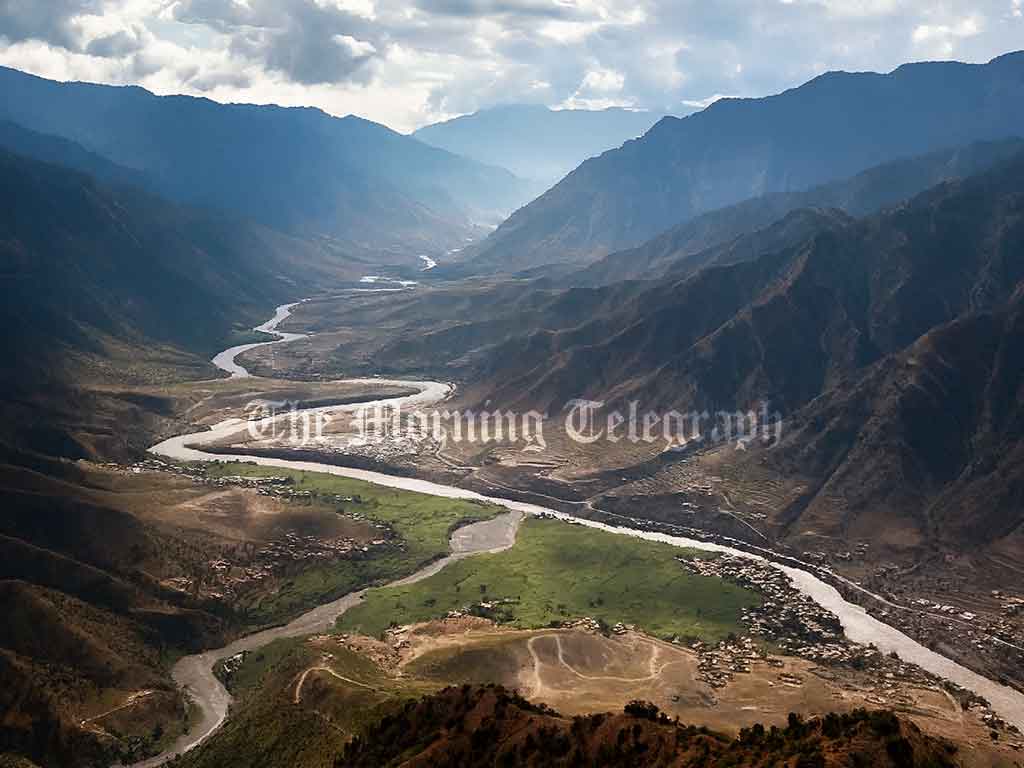

The Durand Line is more than a boundary. It is a scar, a colonial artifact drawn in 1893 by Sir Mortimer Durand of the British Raj, intended to separate British India from Afghanistan. With no regard for culture, tribe, or terrain, the British mapped a frontier that cut directly through Pashtun heartlands, splitting families, tribes, and communities that had long shared the same mountains, valleys, and seasonal grazing routes.

This artificial line was never designed to heal. It was a geopolitical tool meant to secure imperial interests and buffer British India from Russian influence. Yet long after the Raj collapsed, the line remained etched into the modern state system, formalized on maps but rejected in spirit. For Afghanistan, the Durand Line has never been legitimate. For Pakistan, which inherited it after 1947, it is the very basis of its western frontier.

The result is a border that is less a boundary than a provocation. Every military clash along its length is not just about territory but about history. When the Taliban fire across the frontier, they are not simply targeting Pakistani soldiers — they are contesting the legitimacy of a border that was never theirs to accept. When Pakistan retaliates, it is not simply defending its sovereignty — it is defending a line that only empire drew and only one side recognizes.

More than a century later, the Durand Line remains a living wound, one that ensures Afghanistan and Pakistan are locked in perpetual mistrust. It is a border that both divides and defines them, and in doing so, keeps war alive.

The Taliban’s Defiance and Symbolic War

In the latest cycle of violence, the Taliban announced that they had crossed the Durand Line, stormed Pakistani military posts, and killed dozens of soldiers. The group declared the operation a victory and claimed Afghanistan’s borders were now under full control.

This was not just military bravado. It was political theater. For the Taliban, sovereignty is not simply a matter of governing Kabul or enforcing law in Kandahar. It is about proving, through action, that the Durand Line is not legitimate. Each strike across the frontier is both a tactical assault and a symbolic rejection of Pakistan’s authority.

The Taliban’s spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid framed the attacks as proof of strength and independence. By boasting of total control over Afghanistan’s borders, the Taliban sent a direct message: Afghanistan does not and will not recognize the Durand Line as permanent. Every inch of contested soil becomes a stage on which sovereignty is enacted.

This performative defiance is essential to the Taliban’s identity. For decades, Pakistan imagined that a Taliban-led Afghanistan would remain compliant, a client regime willing to accommodate Islamabad’s security concerns. Instead, the Taliban have turned the script upside down. By refusing to acknowledge the Durand Line, they have asserted independence in the most provocative way possible.

For Afghans, this is more than politics. It is existential. Accepting the Durand Line would mean accepting the permanent division of Pashtun lands, the loss of ancestral unity, and the submission to colonial geography. Defiance, then, becomes a national duty — and every cross-border strike becomes a ritual of rejection.

Pakistan’s Illusion of Moral Authority

In response, Pakistan has positioned itself as the rational actor, condemning Afghanistan for “unprovoked firing” and promising a swift response. Interior Minister Mohsin Naqvi stressed that the Pakistani military had shown restraint, while vowing that aggression would not go unanswered.

Yet these statements, while framed in the language of morality, reveal a deeper insecurity. Pakistan seeks to project itself as a responsible state, a defender of civilians, and a military that exercises ethical restraint. But the reality on the ground often tells a different story. Retaliatory airstrikes devastate villages, displace families, and deepen resentment.

Pakistan’s invocation of moral high ground is therefore a form of narrative management. It cloaks the raw realpolitik of cross-border retaliation in the language of civilian protection. The choreography is clear: condemn, retaliate, then appeal for restraint. The cycle repeats, giving Islamabad the appearance of legitimacy while masking the fact that it is enforcing an arbitrary border that one side refuses to recognize.

At the same time, Pakistan’s long-standing accusation that Afghanistan harbors Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants underscores its own fears. The insurgency has cost Pakistan hundreds of lives, especially in its western provinces. Islamabad accuses Kabul of providing shelter to these fighters, while Kabul denies the charge. The truth is likely somewhere in between, but the argument itself is symptomatic of the deeper ambiguity: when the border itself is contested, every accusation of harboring militants becomes both plausible and deniable.

Pakistan finds itself trapped. It cannot retreat from the Durand Line without undermining its territorial integrity, yet enforcing the line invites endless confrontation. Its appeals to morality are therefore less about principle and more about necessity — a performance required to justify a war that can never be won.

A Colonial Fault Line That Refuses to Heal

The structural tragedy of the Durand Line is that it is both invisible and immovable. It is a line that exists on maps and in military orders but not in the hearts of the people who live along it. For Pashtun tribes, the border is a daily disruption. Families straddle both sides, traders move goods across, and fighters cross mountains as easily as herders move livestock. The line is both porous and enforced, ignored and militarized, contested and entrenched.

This paradox makes violence inevitable. Each artillery exchange, each insurgent raid, each retaliatory strike is not a random event but the logical outcome of a border that was never meant to work. The Durand Line is not just a political dispute; it is a structural absurdity.

Pakistan’s attempt to secure it through fences, surveillance, and military posts only amplifies the tension. For Afghanistan, every new checkpoint is an insult. For Pakistan, every insurgent raid is proof of non-compliance. The cycle is not driven by policy alone but by the very nature of the border itself.

It is this inherited colonial architecture that traps both nations in perpetual conflict. Pakistan inherited the line as a de facto frontier, Afghanistan rejected it as a colonial scar, and neither has been able to resolve the contradiction. The result is an endless theater of conflict in which history dictates the script.

The Human Cost of Endless Skirmishes

Lost in the strategic rhetoric are the people who live and die along the frontier. In the past year, insurgent attacks near Pakistan’s western border have killed hundreds of soldiers and civilians. Afghan villages have been scarred by airstrikes, their residents forced to flee into makeshift camps. Entire communities live under the constant shadow of violence, where every day could bring another clash.

For civilians, the Durand Line is not a debate about legitimacy but a lived nightmare. Families divided by the border endure endless disruption. Farmers cannot move freely, traders face restrictions, and children grow up in villages that hear the sound of gunfire as often as the call to prayer.

The rhetoric of civilian protection from both sides often rings hollow. Afghan officials insist they do not harbor militants, while Pakistan insists it acts only in defense. Yet both sides inflict collateral damage. Casualty figures become political talking points, reducing human suffering to numbers on a press release.

For the people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Balochistan, Nangarhar, and Khost, the conflict is not symbolic. It is daily life. The Durand Line has made their homelands into a perpetual battlefield.

The World Watches, But History Dictates

International powers routinely call for restraint and dialogue. Saudi Arabia has urged de-escalation, and other regional actors echo the same. Yet these appeals are often as hollow as the official statements from Kabul and Islamabad. Dialogue is undermined by the structural absurdity of the border itself.

Neither Afghanistan nor Pakistan can afford to give ground. For Afghanistan, accepting the Durand Line would be a moral and national defeat. For Pakistan, rejecting it would unravel its territorial integrity. Both sides are trapped by history. Every appeal to diplomacy crashes against the same colonial wall.

This is why international mediation rarely succeeds. The Durand Line is not just a dispute over boundaries; it is a colonial trauma embedded in the state system. No amount of dialogue can erase the fact that the line itself lacks legitimacy.

The world watches, but history dictates. Each new clash is not a new conflict but the latest act in an old play.

Durand’s Legacy: A Trauma That Cannot Be Buried

The deeper truth is that the Durand Line is not simply a border dispute. It is a wound that has never healed, a trauma that is relived every time a shell is fired or a post is attacked. For Pakistan, it is a frontier to be defended. For Afghanistan, it is a scar to be erased. For both, it is an inheritance of empire that shapes their politics, their identities, and their wars.

This is why the Afghanistan–Pakistan frontier remains one of the most volatile in the world. It is not merely a matter of insurgency or sovereignty, but of history itself. The line drawn by a British official more than a century ago continues to dictate the lives of millions.

Every strike, every protest, every skirmish is part of the same cycle. Until the legacy of the Durand Line is confronted — not just managed — the violence will continue. It is not a matter of policy but of history. And history, unacknowledged, does not fade. It demands to be repeated, again and again, until its truth is faced.

In this grim cycle, there are no heroes, only nations trapped by the past. Pakistan, with its obsession over security, and the Taliban, with its performative defiance, are both actors in a play written long before their time. The Durand Line ensures they will continue to fight, not because they choose to, but because history gives them no escape.