A minister’s urgent appeal to hand over 166 acres of protected forest land to struggling farmers has been blocked, exposing a growing clash between food security and environmental conservation in Sri Lanka.

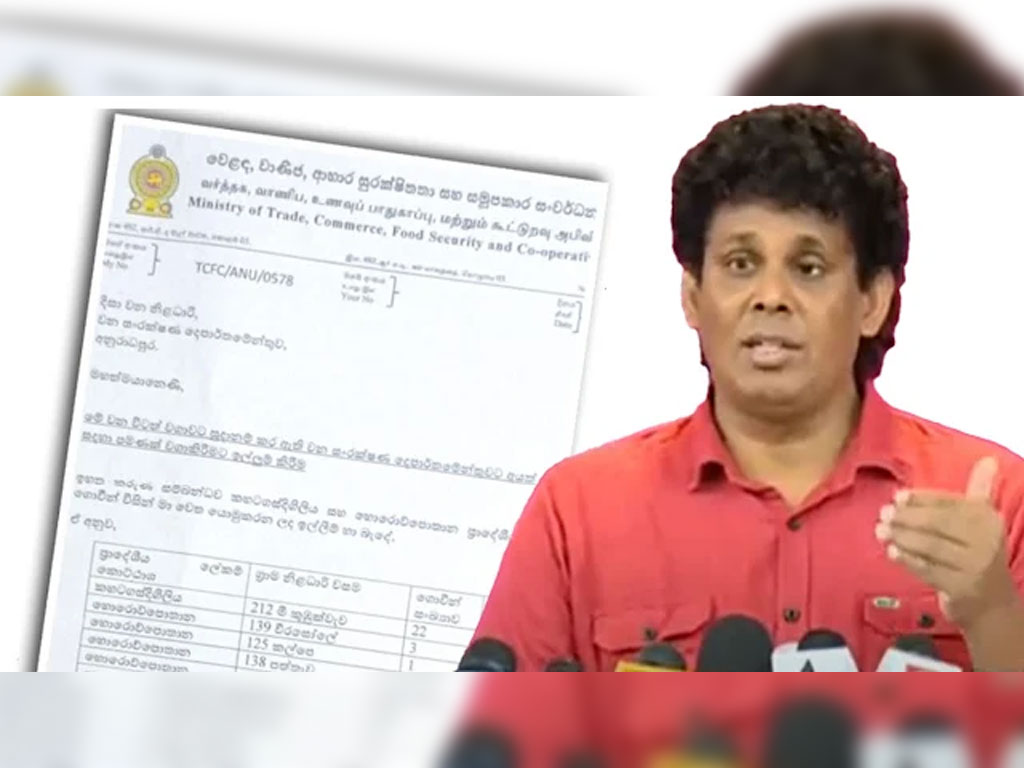

Minister of Trade, Commerce, Food Security and Cooperative Development Wasantha Samarasinghe has requested that 166 acres of lands reserved under the Forest Conservation Department in the Anuradhapura district be released to 71 farmers for cultivation. The request, made through an official letter sent on September 25 to the Anuradhapura District Forest Officer, has now been rejected by the department’s head office. The disagreement has become a focal point in the national debate on food security, land rights, and forest protection.

In the letter, Minister Wasantha Samarasinghe stated that the request was submitted on behalf of 71 farmers across multiple Grama Niladhari Divisions, including Mee Kumbukwewa in the Kahatagasdigiliya Divisional Secretariat and Weerasole, Kalpe, Patthewa, Kanadara, Ratmale and Dutuwewa in the Horowpothana Divisional Secretariat. According to the Minister, these farmers have been cultivating henna during both the Yala and Maha seasons for many years and depend entirely on this land for their livelihood.

The farmers claim that their cultivation work came to a halt after elephant fences were installed, marking the area as part of the reserved zone under the Forest Conservation Department. They further insist that the land they have been using peacefully for years has now been locked away under conservation regulations, leaving them unable to farm and generate income. The Minister has therefore appealed to the department to release the land for this season only, citing urgent economic hardship and the importance of supporting small farmers in a time of national food insecurity.

However, after receiving the letter, the Anuradhapura District Forest Officer sought instructions from the Forest Conservation Department’s head office. The response was clear: the land cannot be released for cultivation as it remains protected under forest reserve regulations. The department’s stance reinforces the legal and environmental position that reserved lands cannot be temporarily allocated, even for agricultural purposes.

This conflict highlights the ongoing tension between conservation laws and livelihood struggles, especially in districts heavily affected by land disputes, elephant-human conflict, and economic instability. While the Minister frames the issue as a matter of crop cultivation and farmer survival, the Forest Conservation Department maintains that releasing reserved lands sets a dangerous precedent that could weaken Sri Lanka’s already threatened forest cover. The farmers, meanwhile, remain trapped between survival and regulation, waiting for a final decision that could determine their future.