A life-saving scientific breakthrough is unfolding as researchers attempt to clinically produce the world’s rarest blood type, a genetic treasure so scarce that only about fifty people on Earth possess it, and one that could transform emergency medicine forever.

Only one in six million people has the extremely rare blood type that lacks the Rh factor, a biological anomaly so scarce that scientists are now urgently trying to recreate it inside laboratories in the hope that it could one day save lives. Blood transfusions have long been recognized as one of the most transformative achievements in modern medicine. Whether a person suffers from catastrophic injuries or requires major surgery, donated blood can make the difference between life and death.

Yet this lifesaving process does not help everyone. People with rare blood types often face immense difficulty in finding compatible blood. This extremely rare blood type that lacks the Rh factor has been documented in only fifty individuals worldwide. If any one of them were to face a medical emergency, the chances of finding an identical match would be dangerously low. For that reason, individuals with Rh negative and ultra rare blood types are encouraged to freeze their own blood, ensuring a supply for their personal medical needs.

Despite its rarity, this blood type is highly valued for reasons beyond its scarcity. It is frequently referred to as golden blood in medical and scientific circles because of its potential value in blood transfusion medicine and immunohematology. This blood type may also open the door to universal blood transfusions as scientists work to solve the immunological challenges that currently limit how donated blood can be safely used.

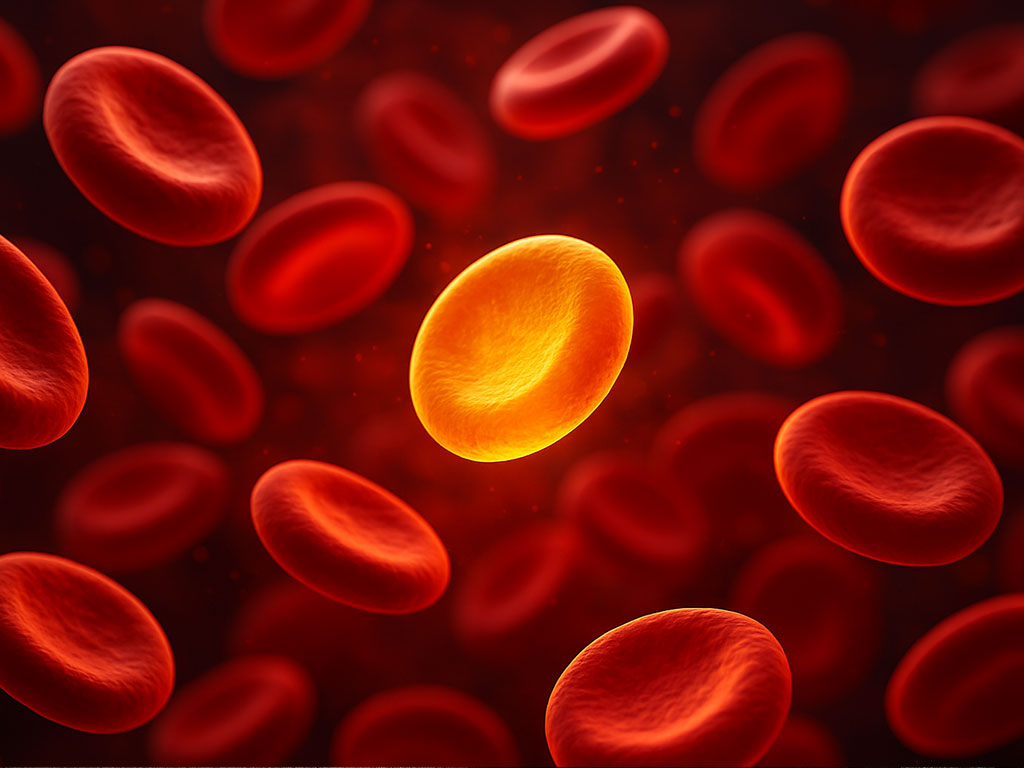

How blood is classified has everything to do with markers found on the surface of red blood cells. These markers, known as antigens, consist of sugars or proteins that protrude from the red cell surface and can be easily recognized by the body’s immune system. If someone receives a transfusion of blood containing antigens that do not match their own, their immune system can produce antibodies that attack and destroy the donor blood. According to Ash Toy, Professor of Cell Biology at the University of Bristol, this immune reaction can become life threatening if a second similar transfusion is given.

Two of the most important blood group systems in generating immune responses are the ABO and Rhesus systems. Individuals with type A blood carry the A antigen on their red cells. Those with type B have the B antigen. People with AB carry both A and B, while type O has neither. Each blood type is further categorized as Rh positive or Rh negative depending on whether the Rh(D) antigen is present.

Although people with O negative blood are commonly described as universal donors because they lack A, B, and Rh antigens, the real story is much more complex. As of October 2024, scientists recognize forty seven blood group systems and 366 different antigens. This means that someone receiving O negative blood could still react to many of the less well known antigens that provoke immune responses. Furthermore, the Rh system itself contains more than fifty distinct antigens. When people say they are Rh negative, they usually refer to the absence of the Rh(D) antigen, but their blood cells still contain other Rh proteins that may vary across the world.

There is also substantial genetic diversity among Rh antigens globally, making it especially difficult for ethnic minorities in different countries to find fully compatible donors. People who are truly Rh null lack all fifty Rh antigens. Because they cannot receive any other blood type safely, but their blood is compatible with most Rh positive types, type O Rh null blood is considered extremely valuable in medicine. In emergency situations where a patient’s blood type is unknown, O Rh null blood offers a low risk of triggering an immune reaction, giving it immense potential to save lives. For this reason, researchers worldwide are searching for ways to recreate this golden blood artificially.

Professor Toy explains that the immune response is significantly influenced by Rh antigens. When these antigens are absent, the risk of immune reaction is lowered. By combining O type blood with Rh null characteristics, a highly valuable and highly compatible blood type is created, although other antigens must still be considered to ensure compatibility.

The origin of Rh null blood has been traced to genetic mutations affecting a protein called the Rh associated glycoprotein, or RHAG. This protein plays a crucial role in red blood cells. When the RHAG protein is altered or reduced due to mutations, the function of other Rh antigens is disrupted, resulting in Rh null blood.

In a landmark 2018 study, Professor Toy and his team at the University of Bristol successfully recreated Rh null blood in the laboratory using immature red blood cells grown under controlled conditions. They then used CRISPR Cas9 gene editing technology to delete the genes responsible for antigens in five major blood group systems known to cause transfusion incompatibilities. These included the ABO and Rh antigens as well as the Kell, Duffy, and GPB antigens. Removing these antigens produced highly compatible blood cells, capable of matching not only common blood types but also ultra rare phenotypes including Rh null and the Bombay phenotype, another extremely rare blood type that occurs in approximately one in four million people. Individuals with the Bombay phenotype cannot receive blood from O, A, B, or AB donors, making laboratory produced universal blood especially valuable.

However, the use of gene editing in blood production remains controversial and heavily regulated in many parts of the world. Bringing clinically produced Rh null blood into routine medical practice will require extensive safety testing and a series of rigorous clinical trials. While this transition may take years, researchers are actively preparing.

Professor Toy has also founded a research company called Scarlet Therapeutics, which gathers blood donations from individuals with rare blood types including Rh null. The goal is to grow long lasting red blood cells in the laboratory and freeze them for emergency use. Toy hopes eventually to produce rare blood banks without needing to rely on gene editing, although editing remains an option to ensure compatibility.

Other researchers are making significant progress as well. In 2021, immunologist Gregory Denome and his team at the University of Wisconsin Madison Blood Institute used CRISPR Cas9 technology to engineer rare blood types including Rh null from human induced pluripotent stem cells. These stem cells behave like embryonic cells and can become any cell type under the right conditions.

Additional scientific groups are exploring similar techniques. A team at Laval University in Quebec successfully converted A positive blood cells into O Rh null cells using CRISPR Cas9. Researchers in Barcelona used stem cells from an Rh null donor to convert their blood from type A to type O, enhancing compatibility.

Despite these promising developments, the ability to produce fully functional artificial red blood cells suitable for human transfusion remains a significant challenge. Growing stem cells into mature red blood cells in the laboratory requires replicating the complex signaling environment found in bone marrow. According to Denome, attempting to create Rh null or similar null blood types may interfere with red blood cell development or cause cell membrane instability, making laboratory production more difficult.

Professor Toy is also leading the RESTORE trial, the world’s first clinical study examining the safety of transfusing healthy volunteers with laboratory grown red blood cells created from donor stem cells. These test cells were not genetically modified, but developing them required a decade of research. Toy emphasizes that traditional blood donation remains far more efficient and affordable for general use, but laboratory grown blood could be highly valuable for people with rare blood types with very few suitable donors.

As science advances, the hope is to create stable, universal, laboratory grown red blood cells that can be used safely in emergencies, complex surgeries, and specialized transfusion medicine. For now, the race to reproduce golden blood continues, driven by the belief that one of the rarest biological substances on Earth may save countless lives in the future.