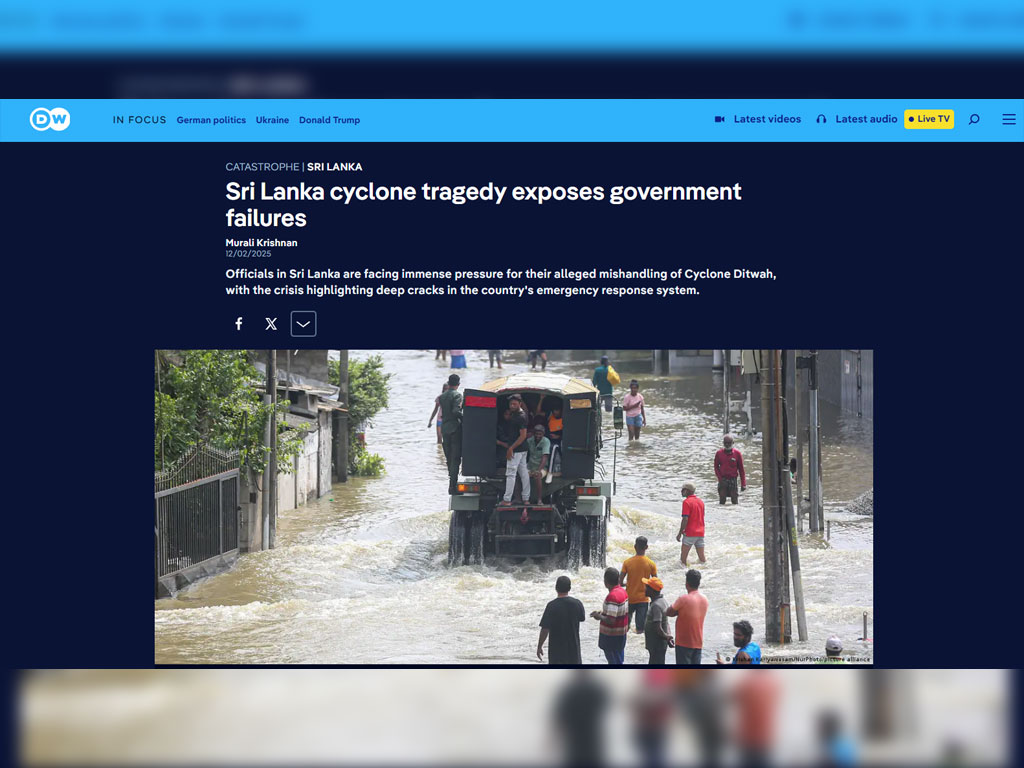

Sri Lanka’s deadliest cyclone in decades has done more than flood homes, destroy roads and uproot millions. It has exposed a government scrambling in the dark, a disaster response system cracking under pressure and a nation left to confront the grim reality that many of the lives lost might have been saved. As Cyclone Ditwah carved its path across all 25 districts, the storm revealed not only the force of nature but the deeper failures of leadership, preparation and communication that allowed a national emergency to spiral into a humanitarian catastrophe.

Sri Lanka’s struggle to cope with the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah has become a defining moment in the country’s disaster management history. What began as a natural calamity has quickly evolved into a national reckoning, with officials facing intense criticism for their alleged mishandling of the crisis. The cyclone tore across all 25 districts, affecting more than 1.46 million people and causing catastrophic flooding described as the worst in nearly twenty years. According to the Disaster Management Center, the death toll has risen to 410, with 336 individuals still missing and more than 64,000 people from 407,000 families now living in almost 1,450 temporary shelters set up by the state.

Multiple countries including India, China, the UK, Australia and Nepal have responded to Sri Lanka’s appeal for support. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake declared a state of emergency in an attempt to mobilize resources and centralize efforts, but frustration across the island continues to grow. Many Sri Lankans feel abandoned as authorities struggle to coordinate relief, issue timely communication and respond to urgent rescue demands. Critics argue that the absence of a unified emergency response has worsened an already catastrophic situation.

Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu, executive director of the Centre for Policy Alternatives, said the government ignored early warning signs that should have prompted immediate action. “The government has not come off well in its handling of the crisis and should have called Parliament to convene urgently to review and strengthen disaster management policies,” he said. He added that “this disaster reveals significant gaps in preparedness and response mechanisms” and insisted that existing frameworks must be assessed to “prevent future failures.”

Experts have echoed his concerns by pointing out that Cyclone Ditwah’s threats were visible long before landfall. Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene noted that the meteorology department had already flagged the possibility of severe rainfall two weeks before the cyclone hit. “Unlike tsunamis, hydrometeorological hazards like cyclones arrive with sufficient notice of several days to take precautions. As early as November 12, Sri Lanka’s department of meteorology had publicly flagged the prospect of extreme rainfall later in the month. That should have triggered a process of preparations across the government at central, provincial, and local levels,” he said. According to Gunawardene, this did not happen, and the state responded only when disaster became unavoidable. He said “the entire disaster management structure from policymakers to state officials should be held accountable for cascading failures that made a bad disaster much worse.”

Legal analyst and public interest advocate Kishali Pinto Jayawardena said the tragedy was intensified because the true threat of the cyclone was not recognized until it was already too late. She stressed that the government must have “the ability and the competence to take critical decisions” in times of crisis and warned that “sentimental outpouring by politicians lauding the people for coming together in times of crisis does not substitute for that duty.”

As the flooding expanded, it became clear that rescue teams were overwhelmed. Former LTTE member Sivanathan Navindra said the northern districts had been cut off, with destroyed roads, collapsed communication lines and total power outages. “The situation in northern Mannar, Mullaitivu, Vavuniya and Kilinochchi districts is extremely severe. Mullaitivu has experienced a total power outage with telecommunication towers down, leaving residents without phone or internet access,” he said. Road closures have made movement impossible between key districts, trapping thousands.

Deputy minister Chathuranga Abeysinghe acknowledged the immense hardship across the island and warned that rising water levels would complicate evacuation efforts. He said that although task forces had been created for relief and assessment, rebuilding would take time. He also admitted that they had difficulty predicting the cyclone’s movement, and the widespread rainfall “stretched rescue teams beyond capacity to reach everyone in need.”

The opposition has been swift to blame the government for the mounting death toll. SJB spokesperson S M Marikkar said his party will initiate legal action, comparing the disaster to previous national tragedies. “Similar to the criminal case filed against the Rajapaksas for bankrupting the nation, we will file a case against the current government, as they are responsible for every citizen that died in the disaster,” he said.

Communication failures have also come under scrutiny. Disinformation analyst Sanjana Hattotuwa said essential warnings and updates were largely issued in Sinhala, occasionally in English, but “rarely, if ever in Tamil.” With Tamil-speaking communities heavily impacted, he said the lack of multilingual alerts contributed to an information vacuum during critical hours. He stated that “if information was available in a more effective and timely manner, lives now lost may have been saved.”

As Sri Lanka continues to navigate the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah, the questions surrounding accountability, preparedness and governance grow louder. Families displaced by flooding and landslides are still waiting for clarity on when help will arrive and when normal life can resume. The cyclone has forced the nation to confront not just the power of nature but the consequences of systemic neglect, policy stagnation and institutional fragility that allowed a preventable tragedy to escalate into one of the worst disasters in modern Sri Lankan history.