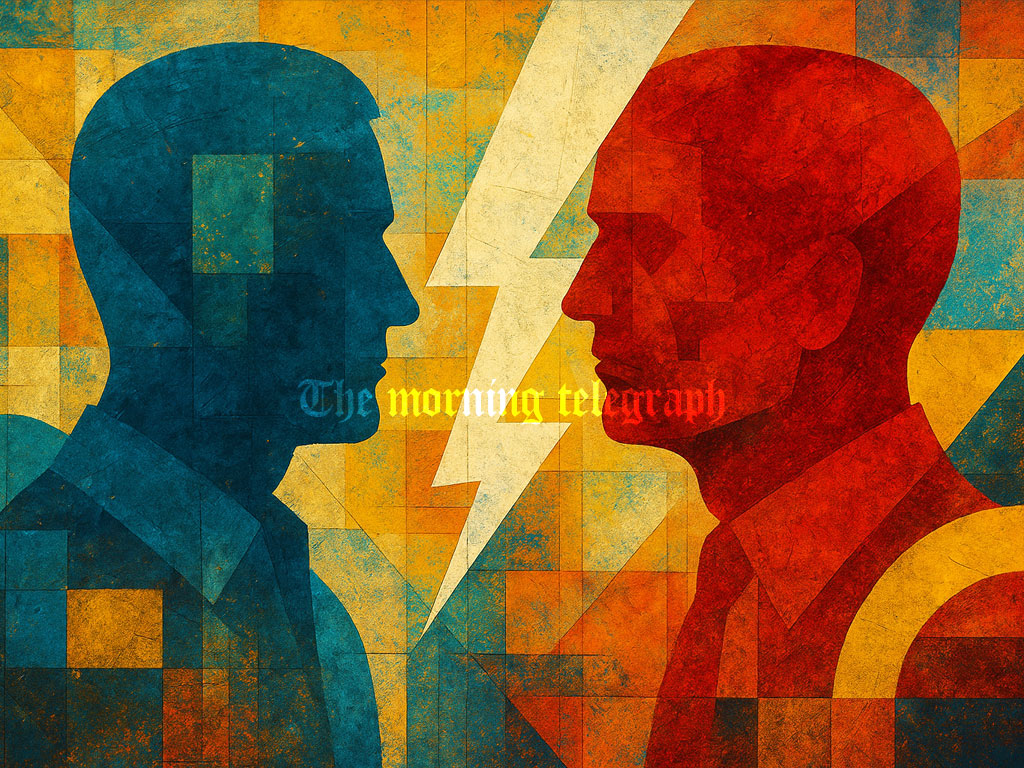

From George W. Bush choosing Bill Clinton over party politics to Sri Lanka’s own missed chance after the 2004 tsunami, this story asks a hard question: why is national unity embraced in words but resisted in practice when disaster strikes again under Cyclone Ditwah?

When the devastating tsunami of 2004 struck, George W. Bush was serving as President of the United States, while Bill Clinton remained a towering figure in the rival Democratic Party. Faced with the suffering of millions across Asia, Bush made a decision that placed humanity above political rivalry. He appointed Clinton as his special envoy to mobilise international aid and reconstruction funds. Bush understood that Clinton’s global relationships made him the best person for the task. He was unconcerned about political credit or partisan optics. What mattered was getting the job done.

That moment illustrated a universal truth. Disasters do not recognise party lines, ideologies, or past hostilities. In any country, calamities such as tsunamis and cyclones create rare moments when governments and oppositions are compelled to stand together. It is like friends and enemies gathering at a village funeral, where grievances are temporarily set aside because grief belongs to everyone.

In Sri Lanka, however, unity has often been fragile. At the time of the 2004 tsunami, LTTE leader Velupillai Prabhakaran was deeply hostile towards the Sinhalese state. He had already withdrawn from peace talks and rejected engagement with the Colombo government, even under pressure from international mediators including the Norwegian peace envoy. He insisted the government could not be trusted. Yet when the tsunami struck, fear replaced defiance.

The disaster killed tens of thousands across the south and the north and wiped out entire communities. Faced with the scale of destruction, Prabhakaran realised that relief for affected families required cooperation with his sworn enemy, the Colombo government. Donor countries and peace envoys proposed a joint mechanism, the Tsunami Relief Board, through which aid could be distributed to both government and LTTE controlled areas. Sri Lanka stood to receive substantial international assistance through this arrangement.

At that time, President Chandrika Kumaratunga had formed a new government following the 2004 general election, replacing the Ranil Wickremesinghe administration. The JVP, which was part of Chandrika’s coalition, emerged as the fiercest critic of the proposed joint mechanism. It warned that any interim arrangement with the LTTE would divide the country and compromise sovereignty. Chandrika herself initially echoed concerns that granting such authority to the North was dangerous.

Yet the tsunami changed political calculations. Chandrika’s government, which included JVP ministers such as the current President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, faced immense international and humanitarian pressure. When donor countries pressed for the Tsunami Relief Board, both Chandrika and Prabhakaran felt compelled to agree. Chandrika viewed the mechanism as essential to channel funds to victims and rebuild devastated areas. Prabhakaran reluctantly agreed because even LTTE members in the North had been left helpless by the disaster.

The JVP responded with political ultimatums. It pressured Chandrika to abandon the Tsunami Relief Board and threatened to withdraw from the government. Chandrika was forced to choose between political survival and humanitarian necessity. When Prabhakaran set aside hostility and accepted the mechanism, she concluded she had no option but to proceed. She approved the Tsunami Relief Board despite fierce resistance. True to its word, the JVP withdrew from the government. Senior figures, including Mangala Samaraweera, publicly defended the JVP’s stance. The party then challenged the mechanism in court, bringing the initiative to an abrupt end.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake resigned from his ministerial post in protest. Whether he remembers this episode today is unclear. What is clear is that had the Tsunami Relief Board functioned as planned and donor funds flowed, Sri Lanka’s recovery could have been far more effective. The JVP’s intervention prevented that outcome.

Fast forward to today, and the irony is difficult to ignore. Is the same JVP not now appealing for international aid following Cyclone Ditwah?

US Ambassador Julie Chung publicly stated that Anura Kumara Dissanayake contacted the US Ambassador to India and Trump’s Special Representative for South Asia to seek assistance. The United States initially pledged one million dollars, later increasing it to two million. Yet with total losses exceeding 15 billion dollars, such assistance is symbolic at best. Two million dollars is a pittance against devastation of that scale.

Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa offered to help amend the IMF agreement and engage foreign diplomats to secure aid, acknowledging the absence of a clear government recovery plan. He even met ambassadors independently to mobilise support. At that stage, the government itself had not convened foreign missions to request assistance.

When Sajith extended a hand of cooperation, Anura responded in Parliament with a striking remark: “Please don’t ask for Sajith’s help.”

History offers a stark contrast. After the tsunami, Chandrika invited her political adversary Ranil Wickremesinghe to light oil lamps together for the victims, signalling unity to the nation and the world. She understood that solidarity was essential to unlock international assistance. Despite personal grievances, Ranil accepted because the tragedy affected everyone.

Cyclone Ditwah has not spared voters of any single party. Those who supported the Compass, the Samagi Jana Balavegaya, and the Podujana Peramuna have all suffered. This is not only a humanitarian disaster but a profound economic shock to the entire country. When opposition leaders offer help, this is not the moment to say “please don’t.” It is the moment to say “please come, let us come together.”

If this lesson is ignored even after Ditwah, Sri Lanka risks learning it again through an even greater disaster.