A sweeping new study uncovers how Environmental Impact Assessments in Sri Lanka repeatedly fail to protect people, turning mega projects into long-term social and environmental disasters.

A new study examining Environmental Impact Assessments in Sri Lanka has found that the quality of reporting on how development projects affect communities remains consistently poor, often failing to identify, predict, evaluate, and mitigate social impacts before critical decisions are made. As a result, EIAs frequently fall short of their core purpose of safeguarding people living near large-scale development projects.

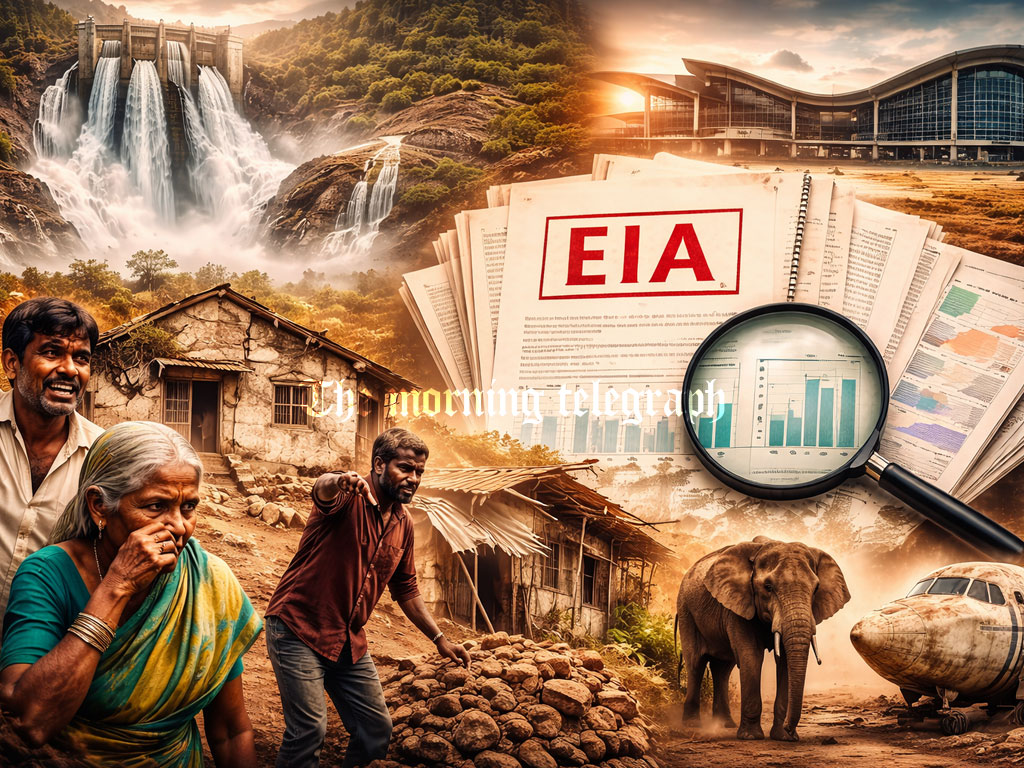

The report, titled “Assessing the Assessments: An Analysis of Social Impacts Reported in Environmental Impact Assessments in Sri Lanka,” was published by the Centre for a Smart Future in Colombo. It highlights two high-profile projects, the Uma Oya Multipurpose Development Project and the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, as case studies that illustrate the real-world consequences of weak social impact assessment practices.

According to the study’s author, Senith Abeyanayake, the Uma Oya project has drawn public attention for decades due to design flaws, politicisation, and resistance from affected communities. Originally proposed under successive governments, the project was rejected by Asian Development Bank feasibility studies because of technical weaknesses and the risk of adverse impacts. Despite this, it was pushed forward largely for political reasons.

“Though the project is now operational, flaws in preliminary studies and project design caused a nine-year delay and additional direct costs of USD 39 million,” Abeyanayake states. More critically, community-level evidence documents severe socio-economic impacts, including cracked houses, drying wells, water shortages, and livelihood disruption affecting more than 7,000 families. Although the Supreme Court ordered compensation for affected farmers in 2015, many residents have still not received full payments.

The study also examines the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, which opened in 2013 and quickly became known as the “World’s Emptiest International Airport.” Beyond financial losses, the report notes findings from the Auditor General’s Department linking the project to increased human-elephant conflict. These incidents have caused deaths, injuries, and property damage, affecting both communities and wildlife. Operational challenges arising from these impacts led to the establishment of a dedicated wildlife office at the airport, highlighting flaws in site selection and planning.

The research analyzed 250 Sri Lankan EIA reports published between 1991 and 2025. In Sri Lanka, social impact assessments are embedded within EIAs rather than treated as independent requirements. These assessments are guided by project-specific Terms of Reference issued by Project Approving Agencies, resulting in wide variation in scope and quality.

The report identifies significant methodological weaknesses. Around 45 percent of EIA reports fail to explain how social impacts were identified or evaluated, while 85 percent do not disclose assumptions or limitations. This makes it difficult for the public to judge the credibility of findings. Consultants often reuse identical impact descriptions across unrelated projects, listing generic risks such as increased smuggling or social misconduct without site-specific evidence.

More than half of the reports do not classify impacts by scale, reversibility, or duration. Among those that use numerical scales, most fail to explain what the values represent. The study also highlights troubling language that stereotypes rural or low-income communities, and in some cases labels political movements or trade unions as negative social impacts.

Accessibility and transparency remain major concerns. Executive summaries are often written in technical jargon, while some reports exceed 500 pages, limiting meaningful public review during the 30-day consultation period. Data disclosure is inconsistent, and many reports include sensitive personal information, raising serious privacy concerns.

Overall, the study concludes that Sri Lanka’s EIA system is undermined by weak methodology, poor data practices, and political influence, underscoring the urgent need for reform to genuinely protect communities.