Modi’s Vision for 2047

In January, thousands braved the freezing cold at Delhi’s Red Fort to hear Prime Minister Narendra Modi deliver a key address. His message, “Viksit Bharat 2047,” represents a pledge to transform India into a developed nation by 2047. Known for his knack for catchy slogans, Modi’s “Developed India” goal remains broad and ambitious.

Since taking office a decade ago, Modi has been working to set the stage for significant economic growth. At the time of his ascent, India was grappling with a precarious economic situation—growth was sluggish, investor confidence was low, and the banking sector was burdened with massive unpaid loans due to the bankruptcy of several billionaires. This crisis had severely hampered the banks’ ability to lend.

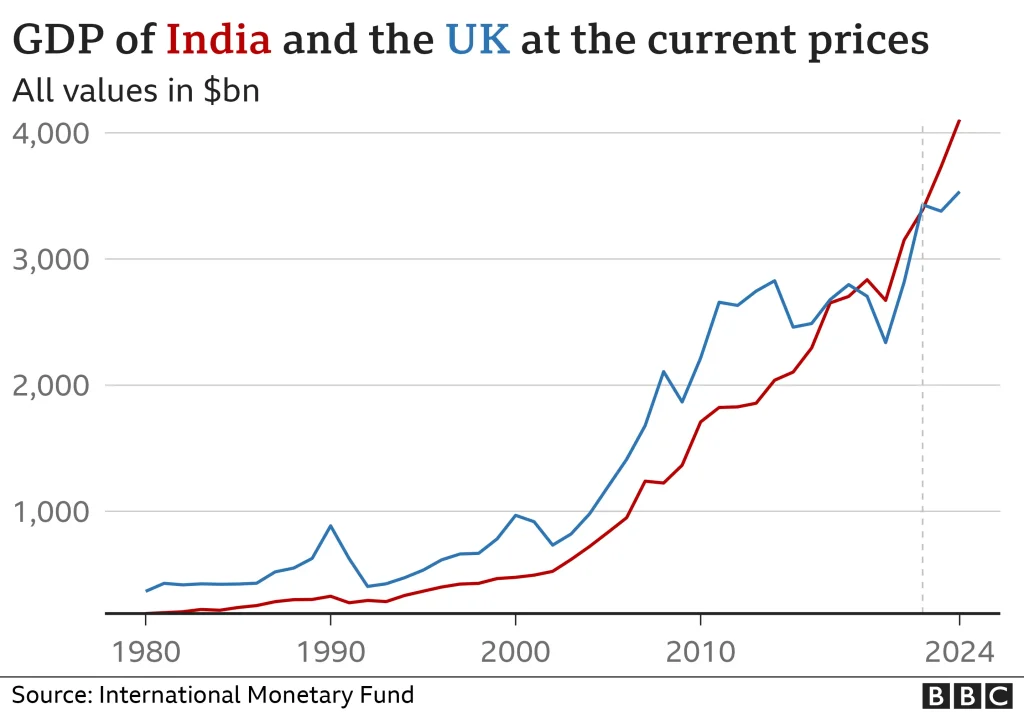

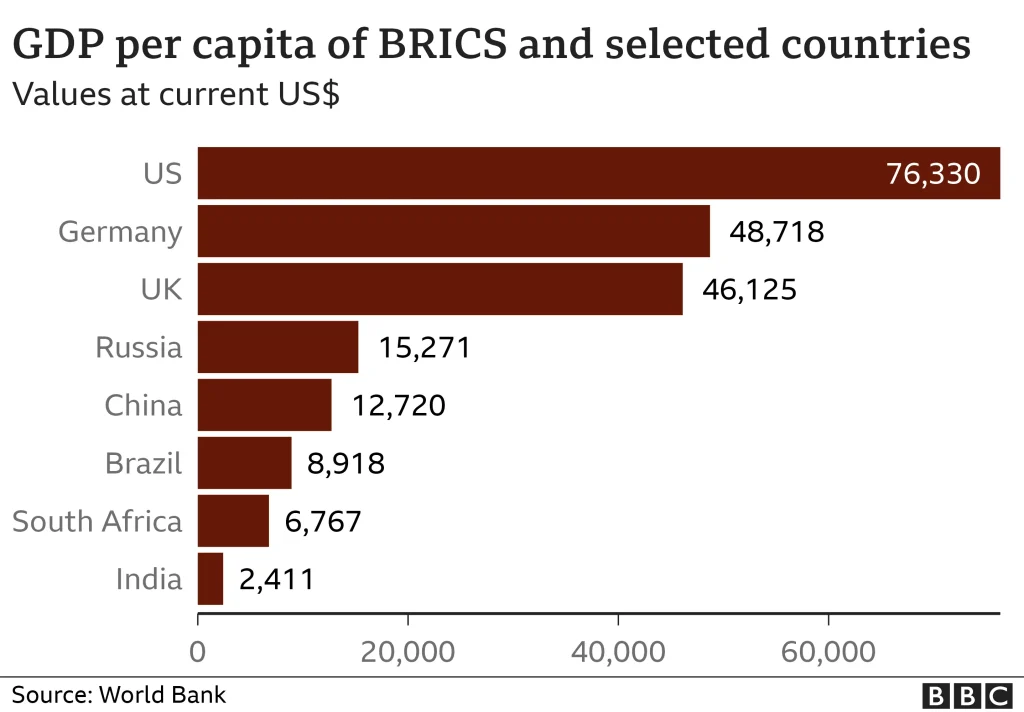

Today, the landscape has shifted markedly. India’s economic growth is now surpassing that of many major economies. The country’s banks are robust, and government finances have remained stable, even amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic. Last year, India overtook the UK to become the fifth-largest economy globally. Analysts at Morgan Stanley predict that India is on course to surpass Japan and Germany, positioning itself as the third-largest economy by 2027.

India is experiencing a notable sense of optimism with several impressive milestones. The country successfully hosted the G20 summit, achieved a historic feat by sending a rocket near the Moon’s south pole, and has witnessed the rise of numerous unicorn startups. Additionally, the buoyant stock markets have positively influenced the wealth of the middle class. These achievements reflect the apparent success of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s economic vision, “Modinomics.”

Despite the surface-level successes of “Modinomics,” the situation is more intricate beneath the surface. While the BJP’s economic policies have driven significant progress, a significant portion of India’s 1.4 billion people still struggle with basic sustenance. For many, the anticipated economic boom remains out of reach, revealing a disparity between the country’s overall advancement and the lived realities of its most disadvantaged citizens.

The economic reforms and growth have undoubtedly benefited certain segments, especially the wealthy and middle class. However, the prosperity touted by “Modinomics” has not been evenly distributed. A substantial number of individuals continue to face hardships, illustrating a gap between the nation’s overall progress and the tangible improvements experienced by its more vulnerable populations.

Digital Revolution

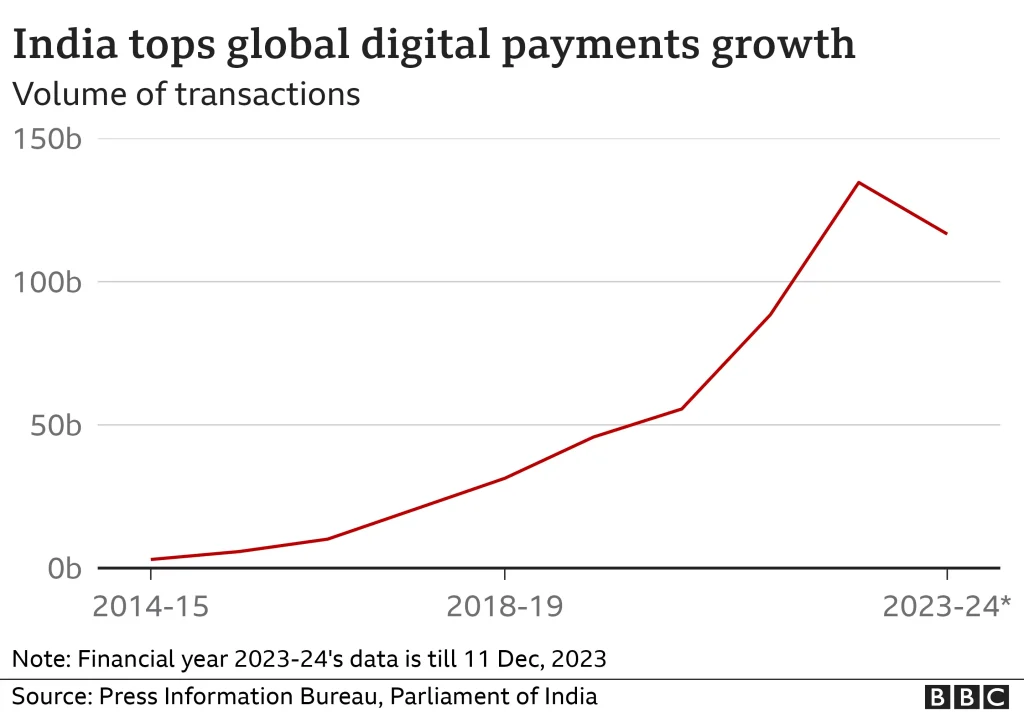

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s emphasis on digital governance has markedly improved the lives of some of India’s most impoverished citizens. Today, even those in the most remote areas of the country can purchase everyday items like a packet of bread for as little as 20p using a QR code on their mobile phones, eliminating the need for cash transactions.

This digital transformation is supported by a three-tiered system: universal identity cards, a payment infrastructure that facilitates instant money transfers, and a data pillar providing access to essential personal documents such as tax returns. The integration of hundreds of millions of bank accounts into this “digital stack” has significantly reduced bureaucratic inefficiencies and corruption.

By March 2021, it was estimated that digital governance had saved approximately 1.1% of GDP. These savings have enabled the government to distribute social subsidies, provide cash handouts, and invest in infrastructure development while maintaining manageable deficits.

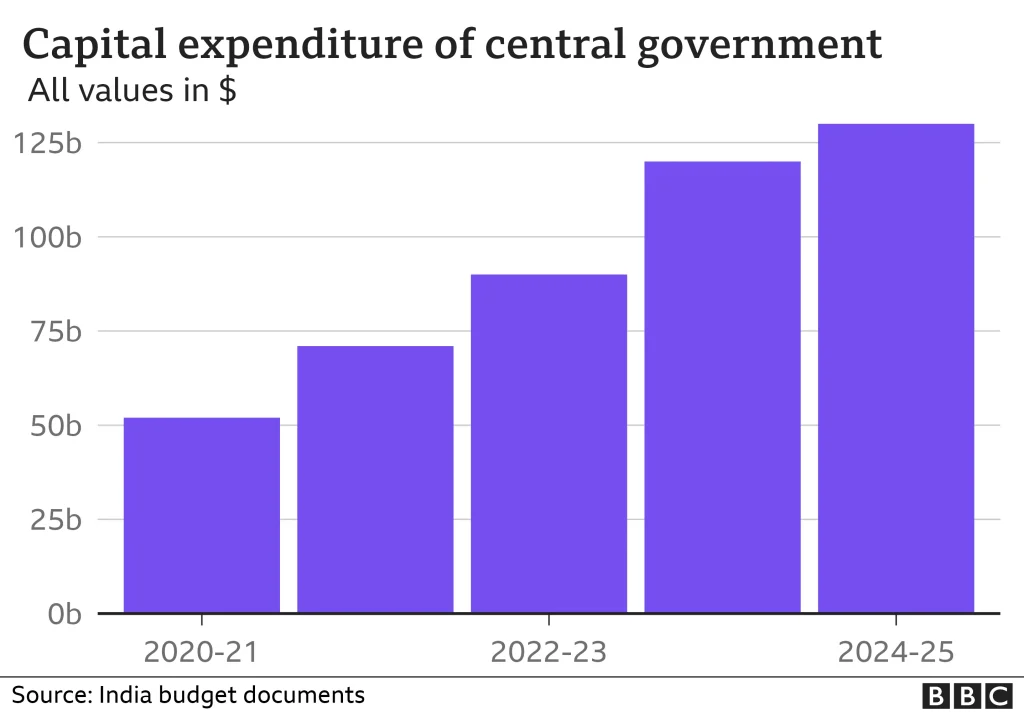

Infrastructural Development

Across India, the landscape is filled with cranes and JCB machines as the country undertakes a substantial overhaul of its aging public infrastructure. Notably, the new underwater metro in Kolkata exemplifies this ambitious facelift.

Infrastructure development has been a cornerstone of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s economic strategy. Over the past three years, the government has invested over $100 billion annually in infrastructure projects. During the period from 2014 to 2024, nearly 54,000 kilometers (33,554 miles) of national highways were constructed, doubling the length built in the previous decade. This extensive infrastructure development also includes new roads, airports, ports, and metro systems.

Modi’s administration has also made strides in reducing bureaucratic hurdles, a long-standing challenge for India’s economy. However, these policies have not been universally beneficial. The severe lockdowns during the pandemic, the enduring effects of a 2016 cash ban, and the problematic rollout of a new Goods and Services Tax—intended to simplify the complex system of indirect taxes—have had significant negative impacts.

The vast unorganised sector, comprising small enterprises crucial to the Indian economy, continues to struggle with these changes. Additionally, private sector investment has declined sharply, falling to just 19.6% of GDP in 2020-21 from a high of 27.5% in 2007-08.

Jobs Blues

In January, thousands of job seekers converged outside government recruitment centers in Lucknow, hoping to secure construction jobs in Israel. This scene, observed by my colleague Archana Shukla, underscores the severity of India’s job crisis and its impact on aspirations across the country.

Rukaiya Bepari, a 23-year-old graduate from Miraj in western India, exemplifies the struggles faced by many. Despite being the first in her family to earn a master’s degree, Rukaiya’s options are limited due to the lack of local industry. To make a living, she has taken up tutoring, which offers minimal income. Both she and her brother have been unemployed for the past two years, reflecting a broader issue.

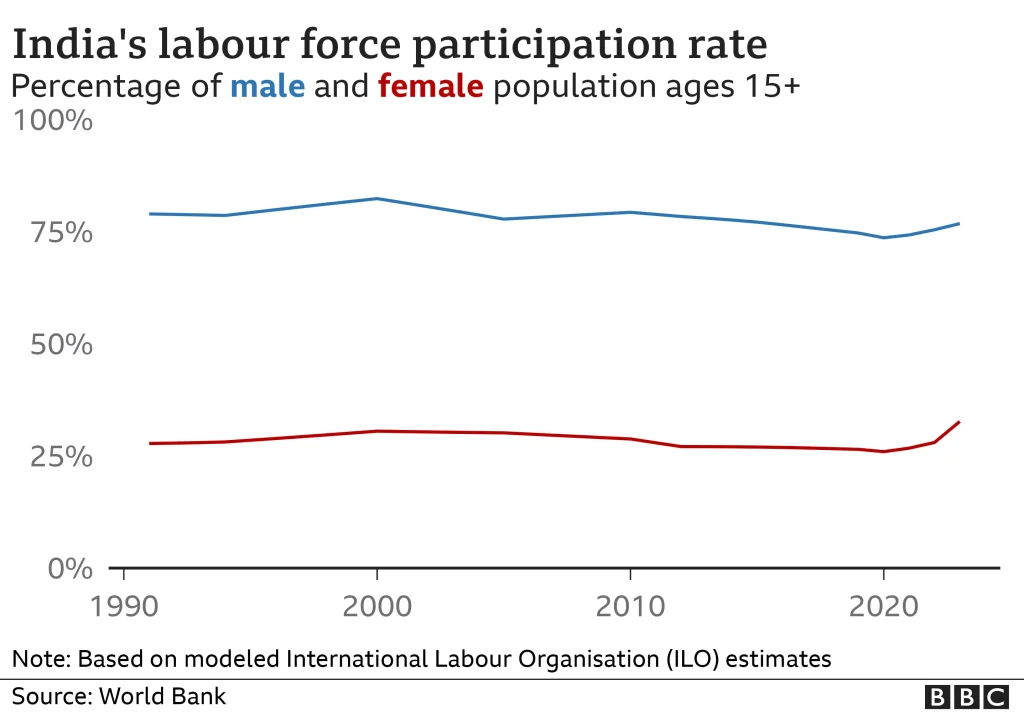

According to recent figures from the International Labour Organization, the proportion of educated youth among the unemployed has risen from 54.2% in 2000 to 65.7% in 2022. Furthermore, real wages in India have shown no significant growth since 2014, as noted by developmental economist Jean Dreze. The World Bank’s regional economist has warned that India risks squandering its “demographic dividend”—the economic potential of its large working-age population.

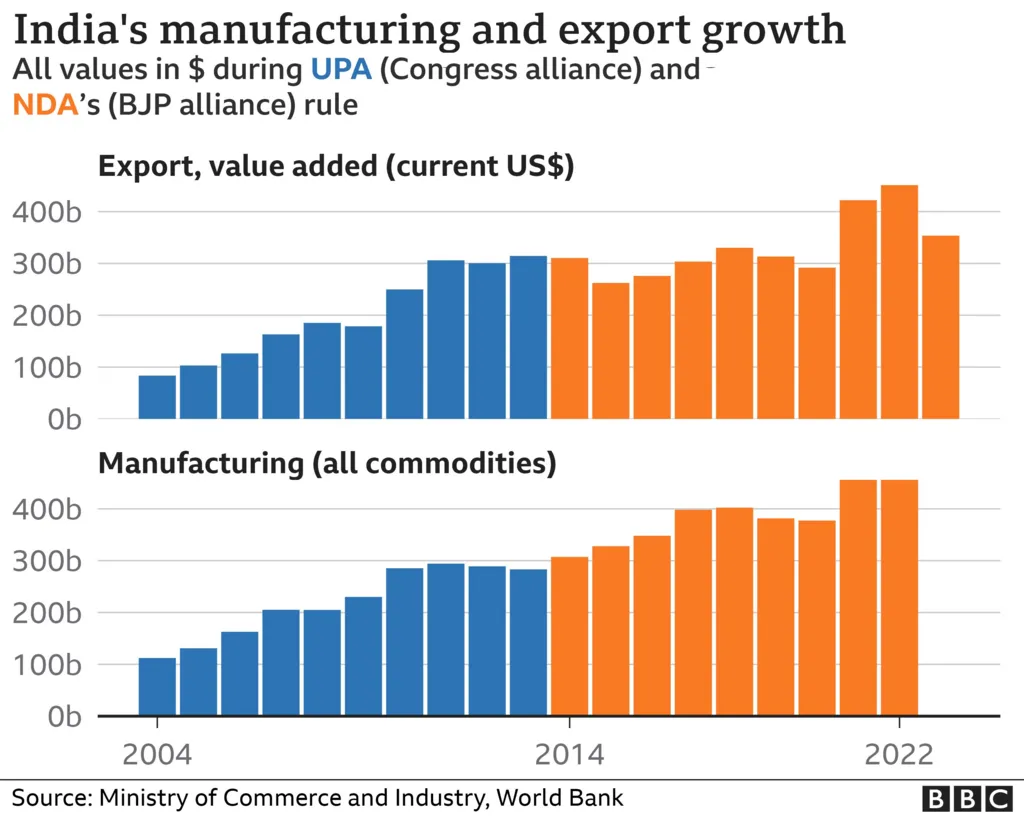

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has struggled to address the job creation challenge. After his 2014 election victory, Modi launched the “Make in India” campaign to transform the country into a global manufacturing hub. In 2020, his government allocated $25 billion in incentives to attract investment in various sectors, including semiconductors and mobile electronics.

However, tangible success has been elusive. While companies like Foxconn, which manufactures iPhones for Apple, and other major global players like Micron and Samsung are shifting some supply chains to India, the overall impact has been modest. The share of manufacturing in GDP has remained stagnant over the past decade, and growth in exports was faster under Modi’s predecessors.

Prof. Vidya Mahambare from the Great Lakes Institute of Management points out that even with a projected 8% annual growth in manufacturing until 2050, India’s manufacturing sector will still lag behind China’s 2022 level. The absence of large-scale industry means that half of India’s population continues to depend on agriculture, which is increasingly unprofitable.

Uneven economic Recovery

The uneven nature of India’s economic recovery has significantly impacted household finances. Private consumption expenditure, which reflects how much people spend on goods and services, has grown by only 3%—the slowest rate in two decades. Simultaneously, household debt has reached an all-time high, while financial savings have dropped to their lowest levels, according to recent research.

Economists argue that India’s post-pandemic recovery has been “K-shaped,” meaning that while the wealthy have flourished, the poor continue to face severe hardships. Although India is now the fifth-largest global economy in aggregate terms, its per capita ranking remains at a lowly 140th.

Inequality has reached its highest level in a century, as indicated by the World Inequality Database. This growing disparity has fueled political discussions around wealth redistribution and inheritance taxes. The opulence of the country’s new elite was on full display at the pre-wedding festivities of billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s son. The event, attended by figures like Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates, and Ivanka Trump, showcased extravagant displays of wealth, including diamonds and jewelry from the Mughal era.

Luxury brands, including those in the automotive, watchmaking, and liquor industries, have seen faster growth compared to more mass-market companies, as noted by Arnab Mitra from Goldman Sachs. Viral Acharya, a professor at NYU Stern, observes that the largest conglomerates have thrived “at the expense of the smallest firms,” benefiting from significant tax cuts and preferential treatment in acquiring and managing valuable public assets like ports and airports. Recent court revelations also show that many of these conglomerates have been major donors to the ruling BJP, further highlighting the growing divide between the rich and the rest of the population.

Promise and Challenges

All combined, this presents an inconsistent picture of India’s economy. Despite its problems, experts believe the country is poised for significant progress. Analysts from Morgan Stanley suggest that India’s next decade could mirror China’s rapid growth from 2007 to 2012. They highlight India’s advantages, including a young demographic, the global shift away from China, and ongoing sector clean-ups, such as in real estate. Trends like digitalization, clean energy transitions, and increased global offshoring are expected to drive future growth. The infrastructure push, with improvements in roads, power supply, and port efficiency, is also seen as crucial for long-term benefits, according to DK Joshi, CRISIL’s India economist.

However, alongside focusing on “physical capital,” Dr. Raghuram Rajan, former governor of India’s central bank, emphasizes the need to build “human capital.” Current educational shortcomings are alarming, with a quarter of 14 to 18-year-olds unable to read simple text fluently, as reported by the Pratham Foundation. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated this issue by disrupting schooling, and the government’s continued underfunding of education and healthcare adds to the concern. In its first decade, Modinomics has benefited a select few, but many still face significant challenges. Dr. Rajan warns that without faster and more equitable growth, India may find itself “growing old before growing rich.”

Source :- https://www.bbc.com/news