Sri Lanka’s Parliament braces for a no-confidence showdown against Deputy Defence Minister Aruna Jayasekera, as questions over his role in the 2019 Easter Sunday tragedy collide with political strategy, public outrage, and memories of past scandals.

The government and its opponents are preparing for a no-confidence motion against Deputy Minister of Defence Maj. Gen. (retd.) Aruna Jayasekera, a battle that promises high stakes despite the NPP’s overwhelming majority in Parliament.

Not all Opposition parties are united on the motion. Some argue that it will only help the government consolidate by having its MPs vote collectively, showing strength and dismissing any suggestion of cracks within the NPP parliamentary group. Yet, this does not necessarily mean that every Opposition party will abstain or vote against the motion when it is presented.

The political debate now revolves around whether the motion is ill-conceived. Should no-confidence motions be tabled if victory is impossible? Will defeating the motion silence criticism of Jayasekera, or will it open the door to deeper political fallout? These questions dominate discussions in Colombo’s political circles. They echo a pointed observation by Minister Samantha Vidyaratne, who highlighted the hypocrisy of some Opposition MPs now targeting Jayasekera after having previously protected Keheliya Rambukwella during a procurement scandal as Health Minister.

That earlier no-confidence motion, despite being defeated, helped the then Opposition expose corruption in the SLPP-UNP administration and mobilize public anger. The defence of Rambukwella became a political stain that contributed significantly to the humiliating electoral losses of the UNP and SLPP in 2024. Rambukwella was later arrested and prosecuted for importing fake medicines, vindicating those who pursued him.

President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s refusal to act on Rambukwella, instead daring the Opposition to bring a no-confidence motion, proved to be a political miscalculation. The Opposition lost the vote but gained momentum with the public. The NPP leadership today cannot afford to repeat such an error with Jayasekera, aware that while they may defeat the motion inside Parliament, they risk losing credibility in the court of public opinion.

Without that no-confidence attempt, the Opposition would not have been able to tie Rambukwella’s defenders, including the President and the SLPP, to his scandal. Although the numbers made defeat inevitable, the move inflicted severe political damage. The debate in Parliament magnified allegations, allowing the Opposition to capitalize on the government’s stubborn defence of a tainted minister.

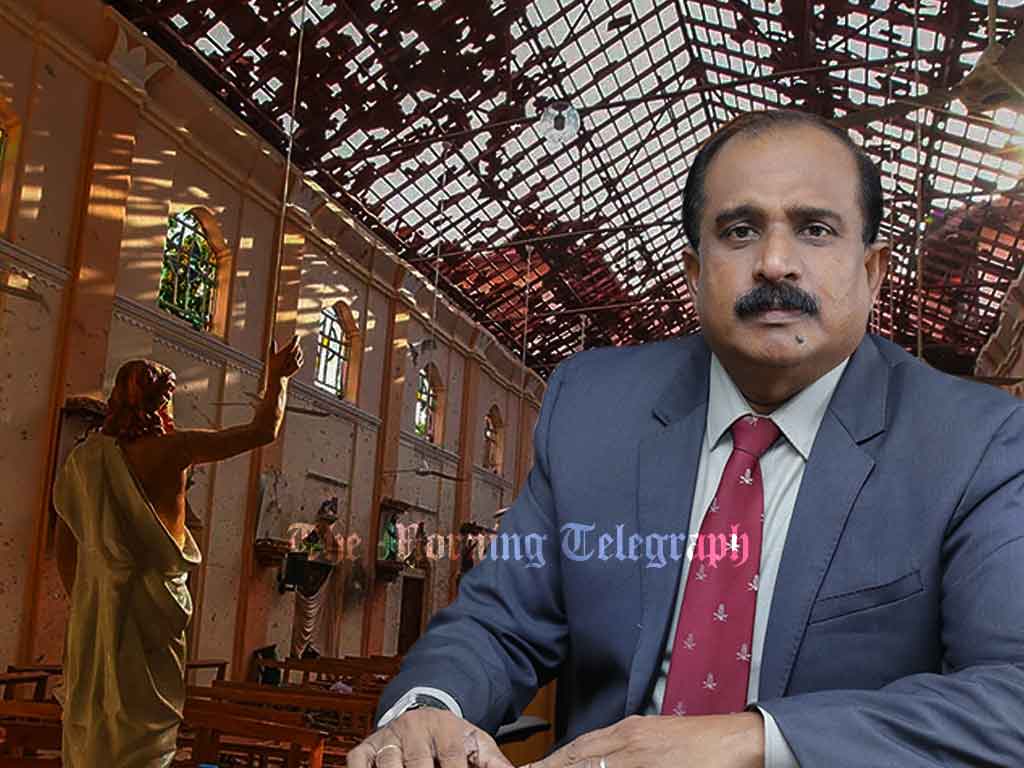

Jayasekera’s case differs in detail but not in political risk. As Security Forces Commander in the Eastern Province in 2019, he was in charge when the National Thowheed Jamath unleashed its Easter Sunday carnage that killed more than 275 people. The Opposition insists it is impossible for the government to argue that Jayasekera never received actionable intelligence on the NTJ’s plot.

This line of attack has been strengthened by Church leaders. Fr. Cyril Gamini Fernando, spokesperson for Archbishop of Colombo Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith, has publicly warned that Jayasekera’s current position as Deputy Defence Minister undermines the credibility of ongoing investigations into the Easter Sunday attacks. For victims’ families, his role remains a wound that has not healed.

The political stakes are therefore much larger than a single vote. Even if the no-confidence motion fails, it can still serve as a potent tool for the Opposition to amplify public distrust, force the government onto the defensive, and reframe the narrative around accountability and justice. Defending Jayasekera may consolidate the NPP in the chamber, but it risks eroding its standing with the wider public, a gamble the government cannot take lightly.

In Sri Lanka’s politics, no-confidence motions are not merely about arithmetic. They are about perception, moral authority, and shaping the story that voters will remember. The Opposition seems prepared to lose the vote but win the war of narratives, just as they did with Rambukwella.

The coming debate will decide whether Jayasekera emerges politically scarred or whether the government can shield him from the fury that still lingers six years after the nation’s darkest day.