Sri Lanka’s new Inspector General of Police steps into office with promises of reform, but history, politics, and corruption may already have stacked the deck against him. Can he transform the police into a guardian of justice, or will his tenure dissolve into yet another act of institutional farce?

The appointment of a new Inspector General of Police in Sri Lanka has arrived with the kind of spectacle more akin to political theatre than genuine reform. His recent address at Colombo University, expected to be a bold vision for renewal, instead delivered little more than ceremonial platitudes. Instead of laying out a roadmap for reinvigorating an institution that is both indispensable and deeply corroded, the new IGP raised doubts about whether this is a turning point or merely another tragic chapter in Sri Lanka’s long-running drama of institutional decay.

The Sri Lankan police have long been described as the veins of the state, carrying the lifeblood of law and order across the nation. Yet those veins are clogged with corruption, politicization, and inefficiency. The system has become the very opposite of what it was created to be: instead of justice, it has become synonymous with fear, servility, and abuse of power. Into this landscape enters a new IGP, praised for his experience in procurement and his claims of disliking political interference. The real question, however, is whether he has the courage and integrity to confront an institution diseased by decades of political manipulation and public mistrust.

His first gesture, the introduction of a WhatsApp hotline, was a case study in performative populism. Rather than demonstrating vision, it exposed a misunderstanding of leadership. The head of the police should not behave like a customer service officer personally fielding complaints. Leadership demands creating systems that function effectively at every level. Sri Lanka does not need a WhatsApp helmsman; it needs a reformer who can dismantle the entrenched culture of corruption, enforce meritocracy, and free the institution from the grip of political patronage.

The historical record weighs heavily on this challenge. The Sri Lankan police embody both valor and disgrace. They have produced heroes who gave their lives for public safety, such as Constable Tuan Saban, and athletes who brought the nation international recognition. But they also carry the scars of some of the darkest chapters in the country’s history: the burning of the Jaffna Public Library in 1981, the violent suppression of the Tamil Conference in 1974, and the massacre of surrendered officers by the LTTE in 1990. These are not distant events but painful reminders of how law enforcement was weaponized for political and ethnic vendettas.

Today’s police force is riddled with structural decay. Officers at lower ranks face low salaries, inadequate housing, and humiliating working conditions. Within the force itself, harassment and discrimination breed what many describe as a “slave mentality,” where unquestioning obedience is rewarded over independent judgment. Even worse, the promotion system is governed not by merit but by loyalty to political masters. Those who serve politicians rise quickly, while those who serve justice are sidelined or punished. The result is a grotesque inversion of values where professionalism is not simply ignored but actively suppressed.

Against this backdrop, the new IGP confronts challenges not of procedure but of moral resurrection. What is needed is structural reform: fair pay and conditions for rank-and-file officers, training that emphasizes ethics and community service over blind obedience, and leadership that cultivates independent judgment and accountability. Reform must shift the culture of policing from command and intimidation to service and protection.

The challenges extend beyond the internal rot. Sri Lanka is in crisis—economic stagnation, political polarization, and rapid technological change have reshaped the landscape of crime. Cybercrime, AI-driven fraud, and cryptocurrency scams are daily realities, yet the police remain focused on outdated practices. Officers still spend their time directing traffic for politicians’ motorcades while lacking the skills and tools to combat international financial crimes. Unless the IGP shifts focus from ceremonial visibility to technological competence, Sri Lanka’s police will remain a relic in a world of evolving crime.

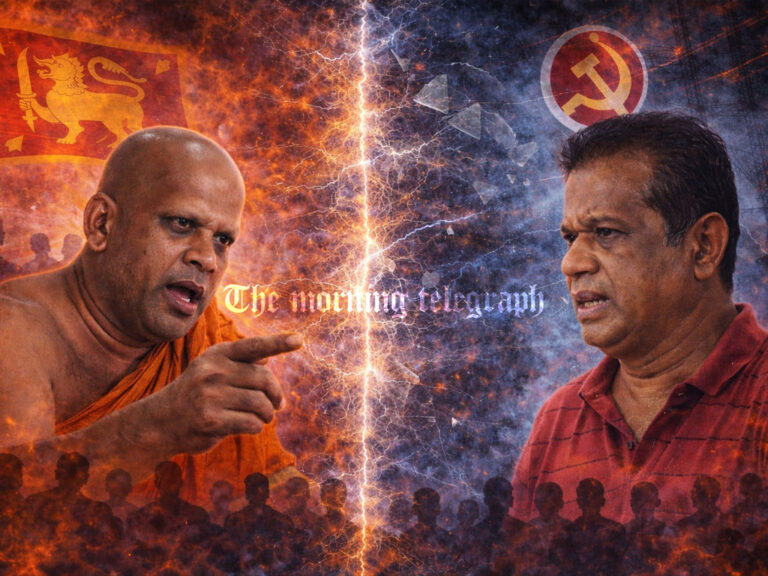

Depoliticization is the most urgent task. Political interference has transformed the police into a partisan militia. Officers who enforce political orders are promoted, while those who resist are sidelined. This culture has obliterated public trust. Citizens do not cooperate with institutions they believe to be corrupt or politically enslaved. Without trust, the rule of law collapses. The new IGP must dismantle the nexus between politics and policing, enforcing merit-based promotions and accountability across ranks. Whether he has the courage to take this path is uncertain.

Reform also requires symbolism. The Sri Lankan police can only regain legitimacy by embodying values of justice, transparency, and accountability. Community policing, multilingual training, and public education must become priorities, especially as the country’s tourism sector grows. Officers must evolve into professionals who understand technology, culture, and community engagement—not just enforcers of outdated routines.

But the obstacles are immense. Politicians resist reform because a neutral police force threatens their power. Corrupt officers resist professionalization because it threatens their profits. Even society itself has become accustomed to a police force that inspires fear rather than respect. Changing this requires not just policies but a transformation of the institution’s very soul.

The stakes for Sri Lanka are monumental. Without reform, public trust will continue to collapse, fueling unrest and weakening an already fragile democracy. But success could spark a renaissance—a police force that protects instead of preys, that enforces justice instead of serving politicians, and that restores confidence in governance.

The choice before the new IGP is stark. He can perpetuate the grotesque theatre of uniformed actors serving political masters, or he can begin the long, painful work of transforming the police into a professional institution. One path leads to collapse, the other to renewal.

Ultimately, this is not just about policing. It is about the very future of Sri Lanka. A nation cannot thrive when the guardians of order are themselves agents of disorder. The question now is whether the IGP has the will to dismantle entrenched corruption and rebuild trust. If he rises to the challenge, he may redeem the institution. If not, his tenure will be remembered as another chapter in Sri Lanka’s tragic theatre of decline.

The police must decide: remain a symbol of fear and servility or rise as guardians of justice and service. That choice will determine not only the fate of an institution but the destiny of an entire nation.