In July 1975, the assassination of Alfred Duraiappah outside a Jaffna temple became more than just a murder, it was the symbolic “first shot” of Sri Lanka’s armed struggle. Once branded a “traitor” for working with Colombo, the Jaffna mayor’s death marked the moment politics gave way to militancy, unleashing a cycle of bloodshed that would haunt the island for decades. This is the story of how one man’s killing lit the fuse for a war without return.

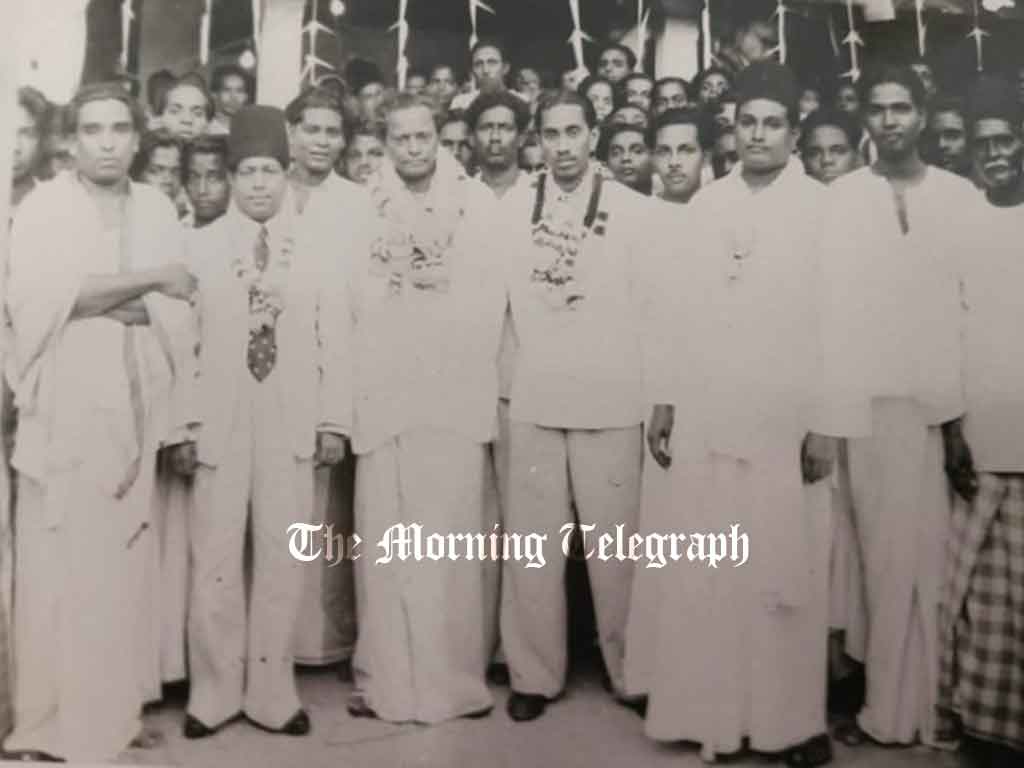

On a Saturday evening in July 1975, Alfred Thangarajah Duraiappah, the Mayor of Jaffna and an influential figure within the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), left his home to attend prayers at a Hindu temple. It was a routine he had followed countless times, blending his Christian faith with the cultural practices of his Tamil community. But that evening marked a violent turning point in Sri Lanka’s modern history. Duraiappah was gunned down near the Varadaraja Perumal Temple in Ponnalai, Jaffna. His killing did not simply end a political career; it signaled the first targeted political assassination carried out by Tamil militants, setting into motion a cycle of violence that would reshape the island for decades.

The triggerman was widely believed to be Velupillai Prabhakaran, then a 20-year-old militant who would later become the leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Though debate lingers over whether he pulled the trigger himself or acted as part of a small group, the murder of Duraiappah has entered both political memory and militant mythology as the symbolic “first shot” of Tamil armed struggle. More than a brutal act, it became a defining story, a narrative through which militancy found legitimacy and through which Duraiappah himself was recast, not as a public servant or community leader, but as the archetype of “traitor.”

Duraiappah’s life and death capture a unique moment in Sri Lankan history. His career embodies the fractured loyalties and blurred identities of Tamil politics in the 1960s and 1970s. His assassination exposes how swiftly rhetoric of betrayal and loyalty could be weaponised in a community struggling with both marginalisation and division. And the legacy of that killing, the justification of violence in the name of liberation marks one of the darkest turning points in the island’s trajectory, a turn from protest and negotiation to insurgency and bloodshed.

To understand why Alfred Duraiappah was singled out, one must return to the politics of his time. Born into a Christian Tamil family, he rose through the ranks of the SLFP, a Sinhalese-majority party not naturally aligned with Tamil aspirations. As mayor of Jaffna and a prominent figure in the north, he was viewed by critics as the “face of Colombo” in Tamil areas, a man accused of enabling the ruling party’s grip over the peninsula. Yet his defenders remember him as someone who channelled state resources to Jaffna, securing projects, development funds, and facilities that might otherwise have bypassed the Tamil north altogether. In his own eyes, perhaps, he was both loyal to the state and useful to his people.

But loyalty is seldom seen in shades. By the early 1970s, Tamil politics was split between those who sought negotiation with the state and those who saw militancy as inevitable. In that climate, Duraiappah’s willingness to work with Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s government branded him, in the eyes of militant youth, as a collaborator. He was no longer merely a politician; he was labelled an enemy from within. His assassination was justified not on personal grounds but through a political narrative: that he was a betrayer of the Tamil cause. And it was this story, the story of “traitor”, that allowed his killing to resonate so powerfully, far beyond the dusty road where he fell.

The Term “Traitor” and the Rise of Militancy

The word traitor carries a weight heavier than any political label. In Tamil political culture of the 1960s and 1970s, it became a lethal accusation, stripping a person of legitimacy and condemning them to social exile, or worse. Alfred Duraiappah became the living embodiment of that accusation. His service under the SLFP, his open friendship with Sinhala leaders, and his efforts to draw Colombo’s attention to Jaffna were reframed by radical Tamil voices as proof of betrayal. He was not simply a politician with an alternative strategy; he was portrayed as the obstacle standing between the Tamil community and its freedom.

In speeches, pamphlets, and clandestine student circles, the image of Duraiappah was crafted into something larger than the man himself. He was not just accused of compromise but of selling out the aspirations of an entire people. This rhetorical demonisation served a clear purpose: to justify violence. If a man is called a traitor often enough, his elimination begins to seem not only permissible but necessary. And for the generation of young militants coming of age in Jaffna’s politically charged universities and streets, Duraiappah represented the perfect first target.

By 1972, the call for Tamil separatism had hardened. The new republican constitution had removed the last remnants of federalist protection, while Sinhala nationalism consolidated its hold on the state. In the north, the Federal Party’s influence was waning, and its critics accused it of fruitless compromise. In this political vacuum, a younger, more militant movement gained ground, fed by frustration and anger. University students, unemployed youth, and disenfranchised activists looked increasingly towards armed struggle. They saw in Gandhi’s non-violence no relevance, in parliamentary politics no hope, and in electoral leaders no credibility. For them, the time had come to act.

Duraiappah’s problem was not only his SLFP badge but his visibility. As mayor of Jaffna, he was a constant reminder that cooperation with Colombo was possible. For militants eager to draw a line in the sand, that reminder was intolerable. The accusation that he had ordered police violence during a protest at Jaffna’s main stadium in 1974, in which several civilians were killed, cemented his image as complicit with state oppression. Whether or not the claim was accurate mattered less than its resonance. In the hands of activists determined to radicalise the Tamil youth, the story of bloodshed became a rallying cry, and Duraiappah its villain.

The mythology of the traitor, therefore, did two things at once. First, it turned Duraiappah’s assassination into a moral act within militant logic, his death was no longer personal but political, no longer a crime but an act of justice. Second, it sent a chilling signal to other Tamil politicians: collaboration with the state would be punished. The murder thus operated as both execution and warning, a script that would be repeated countless times over the coming years as militants expanded their campaign.

Prabhakaran, still a youth then, understood the symbolic power of the act. Whether he personally fired the fatal shots or merely commanded the operation, his name became entwined with the event. Within militant circles, it was spoken of with awe, the story of a young man striking down the archetype of betrayal. Within moderate Tamil circles, it provoked unease. Was this truly liberation, or was it the opening of a door that could never again be shut?

Duraiappah’s assassination altered the course of Sri Lankan Tamil politics. Once violence is sanctified, it rarely recedes. In the wake of his killing, militant groups grew bolder, while mainstream Tamil politicians found their space narrowing. The politics of debate and dissent were overtaken by the politics of the gun. And from that single shot in 1975, the trajectory of the north began to follow a darker path, one in which accusations of treachery and acts of vengeance became ordinary instruments of power.

The tragedy of Alfred Duraiappah is not only that he was murdered, but that his murder became celebrated. In martyring himself unwillingly, he allowed militancy to martyr its own cause. And from that contradiction—the killing of a Tamil leader by Tamil youth sprang a legacy of suspicion, division, and bloodshed that would dominate Sri Lanka’s conflict for decades to come.

Aftermath, Legacy, and Historical Significance

The murder of Alfred Duraiappah in July 1975 was more than the loss of a single politician. It was the first true rupture in Sri Lanka’s post-independence Tamil politics, a moment when the logic of assassination entered the political bloodstream. From that point forward, the threat of death hung over every Tamil leader who dared to resist militant orthodoxy. No longer was the struggle confined to parliament, platforms, and street demonstrations; it now moved into the shadows of covert cells and young men with guns.

For the Tamil community, the aftermath was deeply divided. Among moderates, Duraiappah’s assassination was a shock, a grim sign that democratic politics was collapsing in the north. They recognised his flaws—his closeness to the SLFP, his role in policing protests, his accommodation of Colombo, but they also recognised that his death opened the door to something far worse. Within militant circles, however, the killing was glorified. It was described as the necessary purging of treachery, the clearing away of obstacles, the beginning of a new era. The duality of this reaction itself revealed the future trajectory: politics was to be polarised, and violence normalised.

The Sri Lankan state responded weakly. Investigations into Duraiappah’s death were perfunctory, and no one was brought to justice. This failure sent an unmistakable signal: Tamil politicians could be killed with impunity. Colombo underestimated the significance of the act, seeing it as merely an internal feud among Tamils, not recognising that it marked the birth of organised militancy. Had the state taken the murder with the seriousness it deserved by protecting democratic actors, holding perpetrators accountable, and addressing Tamil grievances the story of the civil conflict might have unfolded differently. Instead, neglect hardened into policy, and the militants were given space to grow.

The assassination also altered the psychology of Tamil politics itself. To be labelled a “traitor” now carried the risk of death. Cooperation with the state became a mortal gamble. Federalist leaders, Tamil Congress members, even clergy—none were safe from the accusation. Over the next decade, one after another would fall victim to the same logic that had claimed Duraiappah. Each killing narrowed the democratic space, each silence of a moderate amplified the voice of the gun. The lesson was simple: survival depended on radical purity.

For Velupillai Prabhakaran, the murder was formative. It provided him not only with reputation but with a template. Assassination became central to the LTTE’s political strategy: not merely an act of war, but a tool of discipline within the Tamil community itself. From Duraiappah to Amirthalingam, from Neelan Tiruchelvam to Lakshman Kadirgamar, the roll call of assassinations reflects a method first tested in 1975. In that sense, Duraiappah was not only the first victim but the prototype, the precedent that normalised murder as political speech.

The historical significance of the assassination also lies in how it reframed the relationship between Tamil politics and the Sri Lankan state. Before 1975, Tamil demands were voiced in the language of rights, autonomy, and constitutional reform. After 1975, those demands increasingly came through the barrel of a gun. Duraiappah’s death did not cause this transformation alone, but it symbolised the point of no return. Once a Tamil leader could be shot dead at the steps of a temple in Jaffna, the illusion of democratic dialogue was irreparably weakened.

Yet, with time, the assassination has also been reinterpreted. For younger generations of Tamils born into war, Duraiappah is a distant name, often overshadowed by the larger narrative of the LTTE and state violence. His memory survives in fragments, stories of a man who sought development for Jaffna, who was seen at once as servant and betrayer, who tried to play politics in a time when politics itself was collapsing. To some, he remains a reminder that moderation can be fatal. To others, he is the proof that compromise cannot protect against radical rejection.

For Sri Lanka as a whole, the killing resonates as a warning about the fragility of democratic institutions. When assassination becomes normalised, democracy dies quietly, replaced by fear and silence. Duraiappah’s death set the stage for decades in which politics became not a contest of ideas but a contest of weapons. The state’s failure to protect him foreshadowed its larger failure to protect thousands who followed. The tragedy is not just that he was killed, but that his killing was allowed to become precedent rather than exception.

In the end, the story of Alfred Duraiappah is both personal and collective. It is the story of a man who believed he could bridge the divide between Colombo and Jaffna, only to be branded a traitor and cut down. It is also the story of a community turning upon itself, choosing purity over plurality, vengeance over debate. And it is the story of a country that, by failing to intervene decisively, allowed the politics of assassination to shape its history.

Duraiappah’s grave lies in Jaffna, but the echoes of his death travel far beyond. They echo in the broken trust between Tamil leaders and their people, in the suspicion that haunts every attempt at compromise, in the long shadow of a war that consumed a generation. His name may not be celebrated, his portrait may not hang in public halls, but his fate remains a lesson etched into Sri Lanka’s history: that once the word traitor becomes a license to kill, a society begins its descent into unending conflict.