Sri Lanka’s political drama deepens as Ranil Wickremesinghe’s bail ignites an unexpected wave of unity. With accusations of dictatorship, government crackdowns, and secret political deals surfacing, the stage is set for a battle between repression and resistance. Is this the moment the people finally topple the untouchables?

In Sri Lanka’s turbulent political landscape, where history and memory collide with present anxieties, the recent granting of bail to Ranil Wickremesinghe has set off a chain of reactions. For some, it is proof that the people are uniting against a constitutional dictatorship. For others, it signals the government’s growing fear of an awakened citizenry. In both views, one truth remains: this moment is not simply about a man’s release, but about the contest between repression and resilience, between state power and public will.

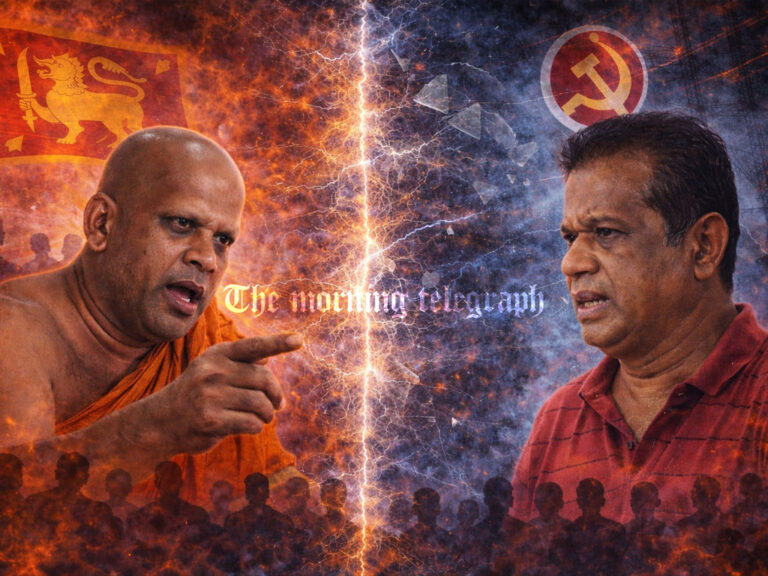

Party leader Sugeeshwara Bandara and central committee members Amila Cooray and Ajantha de Silva of the Maharagama New People’s Front addressed the media, insisting that Ranil’s bail carried profound meaning for the future of the country. Bandara described how citizens from across political divides had taken to the streets in solidarity, no longer passive but unified against what he called a constitutional dictatorship. In his words, the wave of support following Ranil’s release was not an accident but a sign of renewal, “a good omen that a brighter time is dawning.”

According to Bandara, Tilvin Silva, described as the government’s mastermind in Pelawatte, had resorted to intimidating the people who had gathered by using the Criminal Investigation Department and intelligence agencies. National newspapers carried stories about more than twenty politicians being identified as organizers of the demonstrations, with authorities even tracing those who funded buses for protesters. Yet, Bandara ridiculed these tactics, pointing out that while organized crime and drugs flourished unchecked, the government appeared more concerned about citizens boarding buses to express dissent.

The accusation was blunt: a government incapable of curbing criminal gangs and drug networks was pretending to act tough by targeting peaceful demonstrators. “What are they saying?” Bandara asked rhetorically, suggesting that such actions revealed nothing but incompetence.

He argued that the state’s fear was palpable. Instead of governing responsibly, it was relying on repression to quash what he called the people’s uprising. “We are not afraid of repression,” he declared. “We are ready to overcome any challenge.” He insisted that no one was forced or knowingly transported to protests by bus; people came voluntarily, united by respect for democracy and gratitude to Ranil, whom they credited for steering the country during bankruptcy.

The speech was infused with defiance: obstacles, arrests, or intimidation by Anura Kumara Dissanayake would not deter the movement. Bandara urged all citizens to continue the struggle, to protect unity and dismantle what he labeled a constitutional dictatorship.

He turned next to history. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Bandara noted, had once been accused of massacres in the 1970s and 1980s, of arson, of destruction. Ironically, the current government, rooted in the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, carried its own history of burning courts, factories, and buses. To Bandara, there was no greater absurdity than this blood-stained party now filing a case against Ranil under the Public Property Act. “This is not just a joke,” he said, “it is an international joke,” one that would rival the humor of Fredy Silva, Bandu Samarasinghe, or Tennison Kurela. His demand to the government was sharp: stop making a mockery of justice.

Bandara argued that ten months had passed since the government’s first budget, with little to show. No promises fulfilled, no development, no education reforms, and no progress in healthcare. Instead, trade unions were being dragged into the Presidential Secretariat in a desperate attempt to gather information for another budget. He warned the administration to end this nonsense and finally deliver what was promised.

The bail of Ranil Wickremesinghe, Bandara claimed, had revealed fractures within the government itself. While the JVP faction rejoiced, the majority—including the Prime Minister—remained conspicuously silent. He accused Tilvin Silva and Bimal Ratnayake of using Ranil’s arrest to placate their 3% support base, spinning broken promises from the Batalanda Commission and Central Bank cases into political theatre. Posters were being prepared, false promises were being made, but in Bandara’s view, the public could now see through it all.

In this narrative, silence from the “Malaima party” contrasted with the loud excitement of the JVP. Silva and Ratnayake were singled out as central actors, their speeches interpreted as evidence of a long-standing pact with Ranil Wickremesinghe. According to Bandara, the arrest had inadvertently exposed these old political contracts.

Bandara’s criticism extended beyond politicians. He accused Shani Abeysekara, the former CID director, of orchestrating a witch hunt against military officers and intellectuals, alleging that Shani had long been a political tool, cleaning houses for politicians during the good governance era. Now, he argued, Shani was engaged in fabricating cases, targeting decorated military officers such as Ulugetenne, Captain Sumith Ranasinghe, and Janaka Kosala Kumara.

Bandara revisited old testimonies, claiming that witnesses like Wijekanthan and Bharathi had been manipulated to produce false evidence, and accused Shani of continuing to hunt war heroes to satisfy the agendas of the Geneva Human Rights Council. CI Mahinda Pushpakumara, a long-serving police officer, was highlighted as the latest target of fabricated allegations. Bandara recounted in detail Pushpakumara’s involvement in a 2010 case, portraying him as a dedicated officer now unfairly threatened.

The story grew more elaborate: Pushpakumara had resisted pressure to confess to lies, sought protection from the Court of Appeal, and was vindicated when judges ruled that he could not be arrested or made a defendant until the case was heard again in September. Bandara portrayed this as proof of the judiciary’s independence and the failure of Shani, Kandappan, and Ilangasinghe’s conspiracies.

The rhetoric escalated further. Bandara argued that the CID was being weaponized to arrest opposition leaders, exact revenge, and hunt officers for the sake of foreign reports. He warned Shani Abeysekara directly: “Stop this shameful act. No matter how safe you think you are, nature will not forgive you.” Revenge against loyal officers, he insisted, would bring only lasting pain.

Bandara connected the present to the past, recalling similar manipulations during the Thajudeen murder investigation, and declared that the entire country now knew who Shani really was. He even claimed that former naval commanders had appealed directly to President Anura Kumara Dissanayake to ensure justice for Ulugetenne, and insisted that the President had acted based on this “universal knowledge.”

Throughout his remarks, Bandara painted a picture of a government weakened, divided, and desperate. He argued that repression revealed not strength but fear, and that public unity in defense of Ranil Wickremesinghe symbolized hope for Sri Lanka’s democratic future.

The description he offered was both bitter and hopeful: a government scrambling to suppress dissent while citizens, weary of broken promises, gathered voluntarily to demand freedom. For him, Ranil’s bail was not simply a legal decision but a rallying cry, an awakening of the people against dictatorship, incompetence, and deceit.