From Tilvin Silva’s fiery campaign poetry to Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s cautious presidency, Sri Lanka’s political story in 2024–2025 has been one of fragile growth, harsh belt-tightening, and rising despair. Poverty, inequality, stalled reforms, and global headwinds all collide to determine whether Sri Lanka can turn a chequered year into a hopeful future.

Sri Lanka entered 2025 standing at a political and economic crossroads. The promise of change carried by the National People’s Power (NPP) and its Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) allies was rooted in Tilvin Silva’s fiery campaign rallies. His speeches, always ending with poetry drawn from the JVP’s past, appealed directly to the working poor. He would urge the masses with evocative words about “stomachs burning from hunger and hearts burning from grief,” ending with a resounding call: Rise up, rise up, your turn has come. Those words, delivered in town squares and dusty open fields across the island, captured the mood of a people battered by economic collapse, austerity, and widening inequality. But a year later, the question remains whether those promises have translated into tangible relief for the majority of Sri Lankans.

As the International Institute of Democracy and Electoral Assistance warned in September 2025, democracies everywhere face a “perfect storm of autocratic resurgence.” Protecting elections, rule of law, and civic freedoms requires not only defending democratic institutions but also reforming governments to deliver fairness and shared prosperity. In Sri Lanka, that warning rings true. After years of crisis under Gotabaya Rajapaksa and interim survival under Ranil Wickremesinghe, the Dissanayake presidency brought both optimism and apprehension. Supporters hoped the NPP/JVP could lift the burden crushing the working poor. Skeptics feared another experiment in ideology-driven governance could lead to disaster.

By September 2024, Sri Lanka’s social fabric was fraying. The World Bank reported that nearly one in four citizens lived below the poverty line, while over 55% were considered multi-dimensionally vulnerable. The removal of electricity subsidies had worsened matters, pushing over a million households into disconnection and further straining the incomes of the poorest. These realities gave urgency to Tilvin Silva’s campaign rhetoric. His words spoke directly to those who felt abandoned by successive governments—families struggling with daily essentials, workers forced into the informal economy, and farmers unable to bear the costs of fuel and fertilizer.

Despite the despair, macroeconomic figures told a different story. By late 2023, the economy had begun to stabilize, registering positive growth in two consecutive quarters. In the first quarter of 2024, Sri Lanka posted an impressive 5.3% growth rate. Wickremesinghe’s interim government credited its painful reforms, packaged as Gotabaya Sulanga (Gotabaya Wind), for laying the groundwork. Yet this growth brought little comfort to the poorer half of the population. Programs like Aswesuma and Urumaya aimed at targeted relief were inadequate against the tidal wave of impoverishment unleashed by years of crisis. The gap between growth statistics and lived reality widened, leaving many unconvinced that recovery was real.

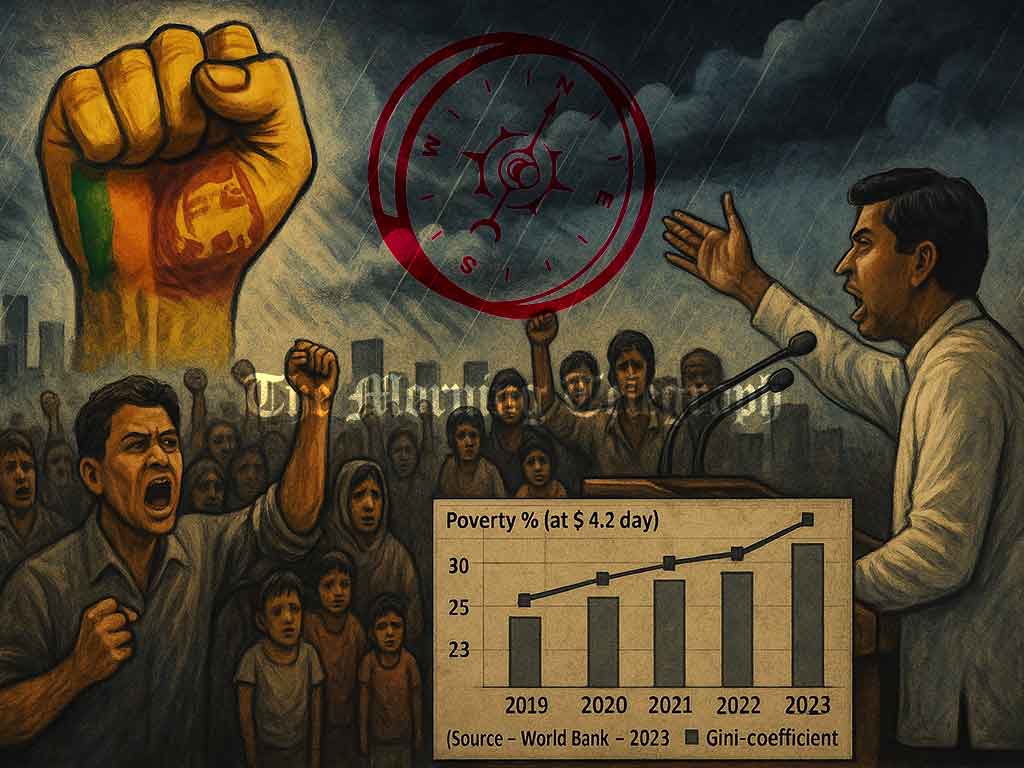

Chart: Poverty & Inequality

| Year | Poverty % (at $4.2 a day) | Gini-coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 11.3 | 37.7 |

| 2020 | 12.7 | 40 |

| 2021 | 13.4 | 40.1 |

| 2022 | 23.1 | 40.4 |

| 2023 | 27.5 | NA |

(Source – World Bank – Sri Lanka Public Finance Review 2025 – Towards a Balanced Fiscal Adjustment)

Against this backdrop, polls in late 2024 showed that 42% of Lankans trusted Anura Kumara Dissanayake more than Wickremesinghe, Sajith Premadasa, or Namal Rajapaksa to address poverty and affordability. Many feared a “JVP Sulanga” that could destabilize the fragile economy. But by mid-2025, those fears had proven exaggerated. The economy stayed on its modest growth path. Yet the real test was not growth, but distribution. Would the benefits reach the ordinary citizen? Here, the record was less encouraging.

Dissanayake’s first year was marked by caution. On economic policy and constitution-making alike, the government avoided radical departures. While this steadiness reassured markets and international lenders, it frustrated supporters who expected bold reforms. Critics pointed to unfulfilled promises: the Online Safety Act remained unrepealed, despite vows to protect free expression. Even more striking was the tardiness in dismantling the extravagant perks enjoyed by former presidents. Only after an electoral drubbing in May 2025 did the government move to scrap presidential privileges. Until then, taxpayers were footing the bill for chefs, personal trainers, and even dog minders serving retired leaders.

The government had in hand the Chitrasiri report, which recommended cuts to presidential privileges. Presented in late 2024, it could have been implemented immediately. Instead, delays left the impression of incompetence—or worse, complicity. Similarly, pledges to curtail perks for parliamentarians fell by the wayside. Asset declarations revealed that most MPs hardly needed lifetime pensions, yet the system endured. Entrenched political interests resisted reform, and the administration appeared unwilling to confront them decisively.

One of the sharpest criticisms of the Dissanayake presidency has been its silence on tax reform. The IMF had made wealth and inheritance taxes part of its conditions. Progressive voices within and outside Sri Lanka argued that shifting from indirect to direct taxation was essential for justice and recovery. Indirect taxes already accounted for over two-thirds of government revenue. Hikes in VAT, such as the January 2024 increase from 13% to 15% and the removal of exemptions on essentials like books, disproportionately hurt the poor. The World Bank estimated that this single measure raised poverty by 2.2%. By contrast, Ranil Wickremesinghe had reduced the share of indirect taxation from 76.7% in 2021 to 66.5% in 2023. Under projections, however, the imbalance could rise again above 75% within three years.

The implications of these economic choices are profound. Food prices remain more than double their pre-crisis levels, wages have stagnated, and job losses continue. As the World Bank observed, households have slashed spending on nutrition, healthcare, and education. This erosion of human capital is sowing long-term damage. Commentators warn that when despair deepens, social unrest follows. Hasan Piker, an American commentator, noted that when people see life as worse than it was for their parents, anger and radicalization become likely. In Sri Lanka, the danger is that unaddressed grievances could be exploited by extremist groups to ignite violence, as seen in past communal clashes.

While Sri Lanka grapples with its own challenges, global politics seep into local narratives. In the UK, right-wing agitator Tommy Robinson resurfaced in 2024 with the backing of a billionaire benefactor. His transformation into a figurehead of anti-immigrant riots underscored how external influences can reframe domestic debates. In Sri Lanka, groups like Sinhala Ravaya borrowed from these toxic currents. Its leaders spread baseless claims that the NPP government was bringing Palestinian refugees to change demographics. Such rhetoric, inflamed by international lobbies, risked reigniting ethnic tensions at home.

The Human Rights Commission’s report on the Digana riots revealed how a road accident was weaponized into anti-Muslim violence by extremist groups. When economic despair reaches boiling point, even minor incidents can spiral into major conflict. The role of groups like BBS and Sinhala Ravaya as fire-starters underscores the fragility of peace. The message is clear: unless the government alleviates economic pain and curbs hate-mongering, the risk of renewed violence is real.

As 2026 begins, the Dissanayake government faces a stark choice. It can either pursue bold reforms—wealth taxes, inheritance taxes, military spending cuts, and genuine political privilege reductions—or continue to drift cautiously, risking disillusionment among its supporters. The stakes are high. If promises made to the masses are not fulfilled, despair will spread. And in that despair lies danger: a fertile ground for lies, extremism, and irrational violence.