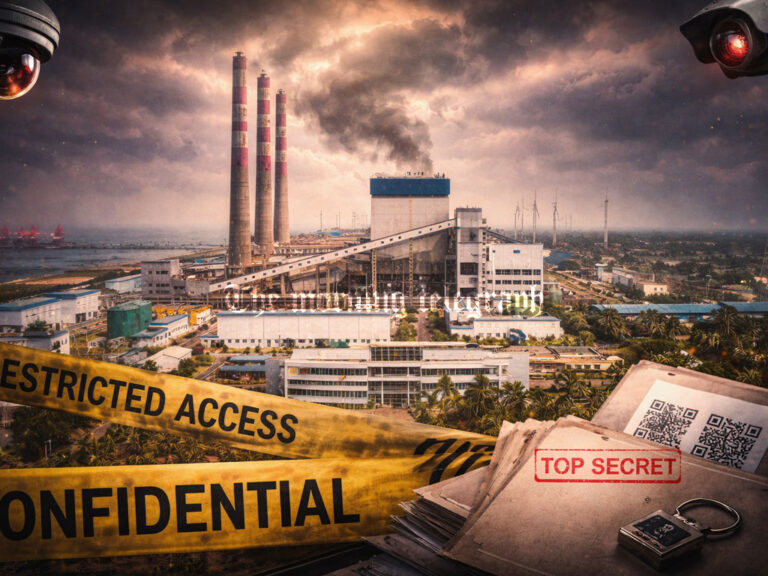

Balochistan’s battle against poppy cultivation has become a high-stakes war where eradication campaigns, displaced Afghan farmers, smuggling networks, corruption, and global drug profits collide, turning the province into the Golden Crescent’s latest epicenter of opium and heroin production.

By September 2025, authorities in Balochistan proudly announced that more than 36,000 hectares of land had been cleared of poppy cultivation. Yet beneath the surface of this so-called success story lies a darker truth. Despite relentless operations by the Anti-Narcotics Force, Levies, Frontier Corps, and Police, poppy fields continue to reappear like a shadow economy thriving on displacement, survival, and demand. Afghan farmers pushed out by the Taliban’s 2022 ban on opium have brought with them sophisticated farming techniques and an irresistible lure of profit. The result is that Balochistan, once seen merely as a transit corridor for Afghan opium, has now become a major producer in its own right within the Golden Crescent.

The timeline of eradication reads like a battle log. On September 17, 2025, over 33,000 acres of land across Killa Abdullah, Chaman, Pishin, Duki, Harnai, Loralai, Killa Saifullah, Nushki, Kalat, Mustang, and Kharan were cleared. Just two months earlier, in July, Levies Forces destroyed 60 acres of poppy in the Toba Kakari area of Pishin. In April, intelligence teams uprooted four acres of illicit fields in Khanozai, Karezat District. In March, a joint operation in Dalbandin, Chagai District, wiped out 100 acres of cultivation. Even in December 2024, small plots near Dalbandin had to be burned. Each operation told the same story: poppy cultivation may be destroyed temporarily, but it always returns.

To strengthen coordination, the Anti-Narcotics Force signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Excise and Taxation Department in April 2025. The deal promised shared intelligence, mutual data transfer, and a system for timely analysis of drug trends. Yet only five months later, Balochistan’s Chief Minister Mir Sarfraz Bugti stood before the provincial assembly warning that the government would confiscate land, arrest offenders, and destroy crops before they matured. His fiery speech revealed a troubling reality: despite massive eradication, poppy cultivation remained stubbornly resilient, spreading under new disguises and threatening to overwhelm enforcement capacity.

The roots of this crisis stretch across the border. When the Taliban enforced their official ban on opium in April 2022, Afghan farmers found themselves without livelihood. Entire communities poured into Pakistan, crossing illegally through smuggling routes into Balochistan. Bribes ranging from PKR 30,000 to 35,000 (about USD 110–125) per person were routinely paid to local police posts. Afghan migrants brought not only desperation but also advanced know-how. With precise seed selection, seasonal timing, and solar-powered wells, they transformed arid land into fertile fields capable of producing high-yield poppy crops. Satellite imagery in June 2025 confirmed 8,100 hectares of cultivation concentrated in Duki and Killa Abdullah alone. Afghan farmers often rent land from local Baloch landowners or enter sharecropping deals, spreading the practice deeper into local society.

The profits are staggering. Beyond raw opium, the flower yields heroin, morphine, and codeine, drugs that feed both illicit trade and global pharmaceutical demand. The international appetite ensures that even when local fields are burned, incentives to replant remain. Smugglers exploit Balochistan’s long porous borders with Afghanistan and Iran, channeling narcotics along the “Southern Route” into Europe and Africa. Reports suggest that powerful actors, from local landowners to corrupt elements in the Frontier Corps, take their share. Allegations persist that the Inter-Services Intelligence and Pakistani Army benefit indirectly from the trade, while groups like the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, seen as a proxy for the Balochistan Liberation Army, may receive funding from traffickers.

The impact on local governance is devastating. Provincial Assembly members such as Zabid Reki raised alarms in July 2025 that Afghan migration had transformed Dalbandin and other districts into new poppy heartlands. Former Chief Minister Dr Abdul Malik Baloch echoed these warnings, declaring that unchecked cultivation threatened not only health but social stability. From Killa Abdullah’s Gulistan area, dominated by Afghan migrants, to Duki’s resettled Afghan farmers, to Chagai’s border zones and Pishin’s expanding fields, poppy now dominates the agricultural landscape. What began as an Afghan displacement crisis has morphed into a Pakistani state security dilemma.

Meanwhile, narcotics seizures underline the scale of the problem. On September 5, 2025, seven suspects were arrested with 25 kilograms of methamphetamine near Quetta. On August 26, the Frontier Corps intercepted a major narcotics shipment outside Khuzdar. On August 7, the Pakistan Navy and ANF seized 1,250 kilograms of drugs worth USD 38 million near Pasni coast, including hashish, heroin, and crystal meth. These are not isolated events but evidence of a thriving pipeline feeding both domestic demand and international syndicates.

To understand today’s crisis, history cannot be ignored. Poppy first took root in Balochistan in 2003, spreading rapidly to Loralai, Chagai, Khuzdar, and Killa Abdullah by 2005. From 2010 to 2020, cultivation shifted from marginal to mainstream, reinforced by high farm-gate prices and porous borders. Security gaps, powerful landowners, and migrant labour created a cycle of periodic surges. Even large-scale destruction campaigns, like those in Loralai and Duki in 2015, failed to stop the tide. Between 2016 and 2020, Pakistan’s Anti-Narcotics Force launched repeated eradication drives, but outcomes varied year to year depending on intelligence and cooperation. The Taliban’s 2022 ban acted as the final push, redirecting Afghan farmers into Balochistan and supercharging cultivation levels unseen before.

Now Balochistan’s role in the Golden Crescent is undeniable. No longer just a corridor, it has become a producer and exporter, feeding a global market while destabilizing its own society. The province’s geography, long borders, and entrenched corruption make it a natural hub. The Southern Route ensures that heroin and opium flow seamlessly from Helmand across Nushki and Dalbandin into Iran, and from there into world markets. Even as the Pakistani state publicly burns fields and signs agreements, the economics of poverty and profit guarantee that farmers will plant again.

At the heart of this struggle lies a paradox. Burning fields may win headlines but provides no livelihood alternatives. As long as farmers earn more from poppy than from wheat or cotton, eradication will remain temporary. Without systemic solutions that combine economic incentives, education, and enforcement, the cycle will continue. Pakistan faces not only international pressure to curb drug production but also internal crises of militancy, weak governance, and corruption. The Golden Crescent thrives on such instability, and Balochistan is now its centerpiece.

The consequences are global. From heroin on European streets to methamphetamine in Asian cities, the drugs grown in Balochistan fuel addiction, crime, and violence far beyond Pakistan’s borders. Each raid, each seizure, each eradication campaign reveals a piece of a much larger puzzle: a transnational industry that turns poverty into profit and instability into opportunity. The real question is not whether Pakistan can burn another 36,000 hectares, but whether it can offer its people, and displaced Afghan migrants, a future not rooted in poppy.

Until then, Balochistan will remain at the heart of the Golden Crescent, a land where enforcement collides with desperation, and where every burned field risks becoming tomorrow’s plantation.