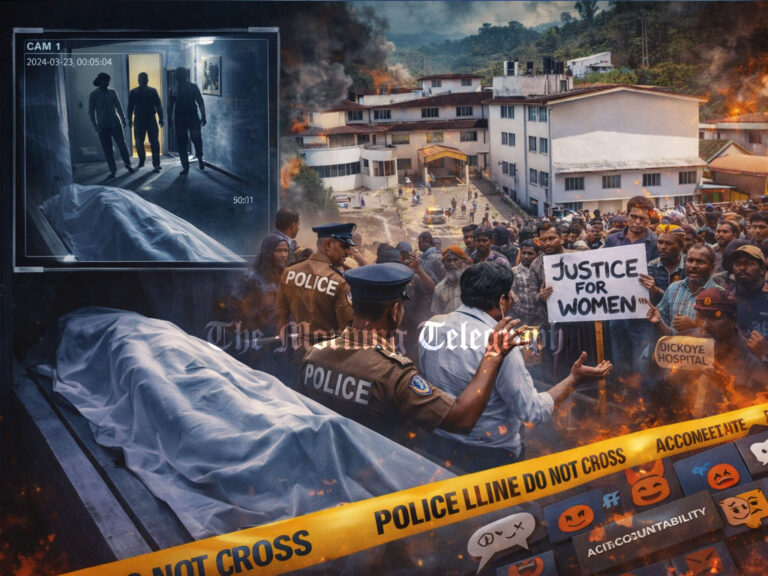

A country drowning in debt and disillusionment is being sold glossy images of “modern leadership,” where every handshake is staged, every smile is rehearsed, and the public is cast as a silent audience while power performs itself instead of serving the people.

In a country where every handshake is filmed in slow motion and every smile is framed for the perfect cutaway shot, Sri Lanka is learning a harsh lesson about Twenty First Century politics. Governance has been reduced to performance. Policy has been polished into promotional content. Citizens, who once believed they were the protagonists of their own democracy, now sit in the dark like ticketed spectators, watching a spectacle that promises transformation and delivers choreography. The camera lingers on the cockpit window, the dignitary’s grin, the carefully scripted exchange of phrases about partnership and progress, while the nation that pays for the production waits for medicine, schoolbooks, and breathable room in a monthly budget crushed by inflation and debt.

This drift did not begin yesterday. Sri Lanka has always had a talent for political theater. From the populist oratory of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike to the triumphalist pageantry of Mahinda Rajapaksa, spectacle has long walked alongside statecraft. What is different under Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya is the refinement of the stage. The raw bluster of the old rally has been replaced by a meticulous aesthetic of governance. Her recent official visits played less like diplomacy and more like high-budget advertisements. The edits were crisp, the optics immaculate, the narrative flattering. What should have been routine state business appeared as an aspirational lifestyle brand, complete with the mood of technocratic confidence that consultant decks call modern leadership.

Sri Lankans are not naive. They can tell the difference between a filmed handshake and a functional hospital. They can feel the gap between a viral clip and a reliable classroom. They do not need academic theory to know when politics is working against them. Still, academic theory helps explain why this keeps happening. Hannah Arendt warned that revolution turns conservative the day after it wins. What begins as a promise to break the order soon becomes a performance to preserve it. Sri Lanka’s postwar and post-crisis political cycles have followed that rhythm with unsettling regularity. The faces change, the grammar of power remains.

This grammar includes donor dependency and creditor obedience, the small print that decides the big picture. Rita Abrahamsen’s analysis of the good governance agenda describes how Western authority was recast in moral language after the Cold War. Democracy became a condition for funds rather than a promise of emancipation. Governments in the global South were invited to perform accountability while staying structurally obedient to lenders. Replace African with Sri Lankan and the sentence does not lose meaning. The choreography of reform is often rehearsal for compliance, and compliance rarely feeds a child or keeps a nurse.

Harini’s ascent from anthropology into national office carries both promise and peril. The promise is obvious. A leader trained to read power, culture, and institutions should be better placed than most to see through rituals that harm people. The peril is less obvious but more common. Technocracy often becomes a mask for dependency. The language of efficiency, evidence, and participation can depoliticize injustice by treating inequality as an administrative problem to be solved with dashboards instead of decisions. James Ferguson called this pattern the anti politics machine. It converts political questions into technical puzzles, and then it praises itself for solving the puzzle it designed.

You can see the machine at work when poverty is redefined as lack of productivity, when failing schools are explained as lack of metrics, when hunger becomes a logistics inefficiency and not a policy choice. You can see it when a minister quotes the size of a spreadsheet but cannot name a living wage. You can hear it when a press conference celebrates a new portal while a patient wonders if the clinic has oxygen. This is what happens when governance becomes branding. The citizen is reimagined as a data point. The voter is resized into a user. The public square is rebuilt as a dashboard that measures everything except power.

Frantz Fanon understood this trap at the moment of independence. The national bourgeoisie, he warned, would step into the colonizer’s shoes and become an intermediary class, fluent in the language of global modernity and loyal to the demands of capital. Betrayal would be less about broken promises and more about substitution. Sri Lanka’s path since liberalization has traced that line with painful precision. The island has mastered the liturgies of governance indices, transparency rankings, and reform roadmaps, but it still struggles to feed households, fund hospitals, and keep young talent from leaving. Success is measured in meetings completed, not in lives improved.

Albert Camus wrote that the slave demands justice and ends by wanting a crown. Revolutions that once took to the street evolve into processions that move from camera to camera. The slow motion handshake is the new crown, heavy with symbolism, light on consequence. The national imagination, once crowded with labor struggles, cooperative movements, and arguments about education, is now colonized by the aesthetics of renewal. The risk is not simply that reform becomes cosmetic. The risk is that citizens begin to accept cosmetics as the only available form of change.

History does not let Sri Lanka pretend this is a local quirk. The Russian Revolution promised workers’ councils and delivered a party state. The Iranian Revolution expelled tyranny and enthroned theocrats. African independence movements traded colonial flags for structural adjustment and comprador elites. The Arab Spring, full of digital hope, was folded back into geopolitics and restored authoritarianism. Kafka’s grim sentence still stands guard at the end of each parade. Every revolution evaporates and leaves behind a bureaucracy, a slime of forms, a residue of rituals that justify themselves with the vocabulary of progress.

To say performance is hollow is only half a truth. Anthropology reminds us that performance can be meaning making. A state can teach people who they are. A leader can help a country rehearse a better identity. If one grants that generosity to Harini’s media choreography, the images are attempts at pedagogy. They project competence in a place where cynicism ruled. They organize the symbols of authority so that a nation sees itself reflected as capable. That is not trivial. It is also not enough.

Antonio Gramsci helps clarify what is at stake. He called it hegemony, the process by which ruling blocs secure consent through culture as much as through coercion. In Colombo, a network of donors, NGOs, think tanks, and elite commentators defines what counts as reasonable politics. Inside that consensus, redistribution appears reckless, sovereignty appears childish, and the only serious words are reform, transparency, investment, and stability. It is not that these words are wrong. It is that they drain the political of its politics. They set the borders of imagination so tightly that the only thing left to do is adjust the lighting.

Arendt also offers a way out. Politics, she argued, is the realm of natality, the human capacity to begin anew. Even a carefully scripted government can produce moments of rupture. A leader trained in anthropology could turn reflexivity against the system that sustains her, naming the networks of dependency and calling them what they are. Such a move would be costly. It would offend donors, rattle creditors, and unsettle a bureaucracy that has learned to survive by pleasing both. The reward would be fragile and worth it. The reward would be democracy that means something.

C. Wright Mills mapped the triangle of power in modern democracies. He saw corporate, military, and political interests forming a durable bloc. In postcolonial states that triangle extends to international finance, NGOs, and bureaucracies. Elections rotate faces across the stage while policy coordinates remain fixed. Privatization, austerity, and investor incentives are locked in place. The public is invited to participate in rituals that look like renewal precisely so that nothing essential needs to move. The smile, the handshake, the cockpit video, these are not acts of rule. They are liturgies of legitimacy.

Harini’s style of rule fits neatly inside a new kind of populism that flatters the managerial class. It is not the stadium of the old demagogue. It is the dashboard of the new technocrat. Managerial populism speaks the language of efficiency and transparency and invites people to believe that an app can do the work of justice. It is seductive because it is polite. It asks for your email, not your allegiance. It promises progress without conflict, accountability without power, transformation without disruption. Sheldon Wolin called the cumulative effect inverted totalitarianism, a regime where corporate and bureaucratic power hollow out democracy while preserving its symbols.

You can see inverted totalitarianism in the way metrics consume meaning. Corruption arrests make headlines while procurement rules remain untouched. Austerity is renamed fiscal discipline and sold as patriotic necessity. Safety nets thin in the name of targeting. Schools are told to compete for grants while teachers buy chalk. Citizens are assured they still live inside a democracy because they vote, because they have an ombudsman, because a portal shows a queue. Meanwhile the decisions that shape their lives are made in rooms where cameras are not invited.

To point all this out and stop there would be to fail the people who must live in the world critique describes. Camus warned that rebellion without hope becomes sterile. The task is to keep hope honest. Sri Lanka’s political imagination must be reset around questions that no camera can answer. Who decides. In whose name. For whose benefit. Those questions are not rhetorical. They are design specs for policy. They are constitutional requirements dressed as curiosity. They are the difference between a government that edits videos and a government that edits laws so that a public hospital can heal the sick without a fundraiser.

What would it mean for Harini’s administration to act like that in the middle of constraint. It would mean telling the truth about the constraints. It would mean publishing the letter of intent to lenders and letting people see what was promised in their name. It would mean admitting that some reforms hurt and then building buffers so that hurt is not distributed downward. It would mean choosing a few priorities that matter to the majority and funding them fully even if something glamorous must wait. It would mean hiring fewer brand consultants and more nurses, fewer media handlers and more math teachers, fewer speechwriters and more inspectors who keep the food supply honest.

It would also mean telling donors something they rarely hear from recipients. The point of aid is not to convert a country into a perpetual pilot project. The point is to help a country end the need for aid. That requires letting it make mistakes, change direction, and protect its people when markets do not. It requires patience with sovereignty. It requires humility from those who fund and those who govern. None of this looks good on video. All of it looks like responsible rule.

Meanwhile, the opposition scripts its own theater. The JVP, once the radical conscience of the island, appears stranded between nostalgia and novelty. Months spent gaming out how to unseat the prime minister have not produced a strategy equal to the facts. Harini’s quiet consolidation of authority surprised a party used to reading the public mood better than anyone. Misjudgments piled up. The result is a counter drama with no set, a chorus with no song. You cannot defeat managerial populism with memory alone. You need a program that names the system and offers more than anger. You need to show people how policy can feel in a grocery bill and a bus stop and a clinic line.

Sri Lanka’s tragedy is not only corruption or incompetence. It is the long outsourcing of politics to performance. Revolutions dissolve into rituals. Reforms collapse into donor reports. Empowerment shrinks into personal branding. An island capable of orchestrating supply chains and choreographing public relations still struggles to deliver dignity at scale. Intelligence manages performance at scale and refuses to manage well being with the same discipline.

Yet the beginning of reversal is not exotic. It is ordinary. It begins when citizens stop clapping for illusions and start counting consequences. It begins when journalists ask rude questions about procurement instead of friendly questions about optics. It begins when civil servants refuse to treat a report as a result. It begins when unions measure success in safety and pay, not in photo opportunities with ministers. It begins when teachers, doctors, drivers, fishers, and the millions who keep this country alive say in their daily choices that they will not be pacified by edited moments.

This is not a call to rage. Rage burns fast and feeds the camera. This is a call to stubborn citizenship. Vote as if the clinic matters more than the clip. Organize as if the bus line matters more than the banner. Petition as if procurement clauses are poetry. Litigate as if the constitution belongs to you. Demand from every party a budget you can read and a timeline you can check. Ask for independent regulators who can shut down tender games. Reward the politician who admits a mistake and punishes a friend. Punish the one who edits a mistake into a montage.

Harini Amarasuriya still has choices. She can keep perfecting the image of a modern leader or she can decide that the image is getting in the way of the work. She can lean into donor friendly grammar or she can rewrite a line in it and see who flinches. She can ask her communications team to produce fewer slow motion handshakes and more real time disclosures. She can remind a weary country that the point of power is not to look competent but to be responsible. If she does, the staging will not vanish. Politics needs ritual. It will simply become a ritual that serves life instead of a ritual that sells it.

If she will not, the country should not wait for a better edit. It should build a better expectation. Do not ask how a visit looked. Ask what it changed for a farmer in Anuradhapura or a seamstress in Galle. Do not ask how many views a clip reached. Ask how many classrooms got books and how many clinics got antibiotics. Do not let any government explain away austerity with the word inevitable. There is nothing inevitable about cutting the poor first. There is nothing inevitable about a tax system that leaves wealth alone and leans hard on wages. There is nothing inevitable about a development plan that builds glass while people need grain.

If all that sounds obvious, it is only because the obvious has been replaced by the aesthetic for too long. Sri Lanka’s future will not be decided by a camera. It will be decided by policy written in daylight, budgets argued in detail, and a public that refuses to be dazzled. The spectacle is loud, but reality has better timing. Electricity bills arrive on time. Bus fares rise on time. School terms begin on time even if classrooms are broken. The calendar of life is a teacher with no patience for edits.

In that sense the path back from performance to governance is not mysterious. Publish the constraints. Debate the trade offs. Choose the public good when it conflicts with private convenience. Accept that donors are partners, not parents. Accept that creditors have leverage and citizens have rights. Accept that the line between sovereignty and survival is often thin and that the job of leadership is to thicken it, inch by inch, year by year, until a country can stand on it without fear.

Sri Lanka has done difficult things before. It has rebuilt after catastrophe. It has educated children through crisis. It has survived a war that tried to unwrite its map. Those successes did not come from beautiful footage. They came from ordinary people doing necessary work while the camera looked elsewhere. That is what will rescue this moment too. A politics that honors that work will deserve the camera and will not need it.

Until then, the slow motion handshake will remain the national metaphor, a crown without substance, a promise without delivery. And the people who pay for the production will continue to sit in the audience, counting their change, measuring their patience, and waiting for the lights to come up on something more than a scene.

SOURCE :- SRI LANKA GUARDIAN