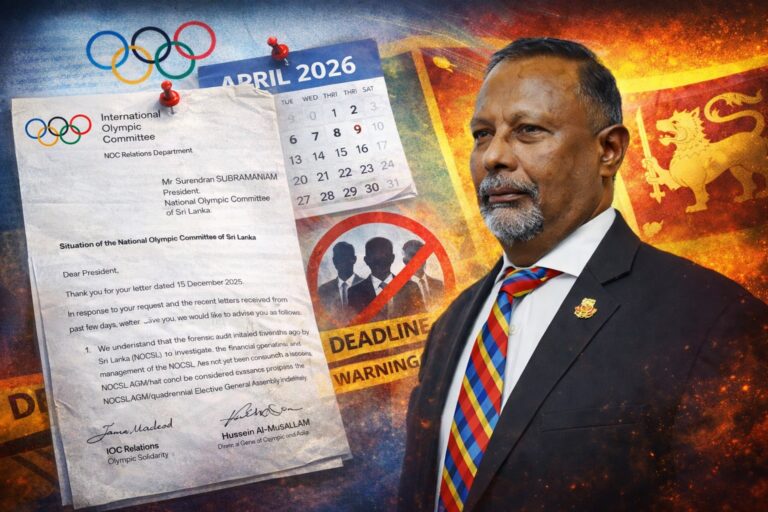

An increasingly public exchange of formal correspondence has brought into sharp focus the governance crisis engulfing Sri Lanka’s National Olympic Committee, while also clarifying where lawful authority currently resides. Although Jaswar Umar, President of the Football Federation of Sri Lanka (FSL), issued a strongly worded letter challenging the legality of the incumbent NOCSL administration, the detailed rebuttal issued by Suresh Subramaniam, President of the National Olympic Committee of Sri Lanka (NOCSL), systematically dismantles each claim with reference to constitutional authority, international protocol, and binding governance obligations.

Subramaniam’s response leaves little room for ambiguity. He asserts that his continuation in office is not a matter of discretion but of necessity, arising from the absence of a validly concluded electoral process and the existence of unresolved financial governance issues that legally preclude the conduct of an Annual General Meeting. Crucially, he emphasizes that his actions are undertaken with the explicit concurrence and ongoing oversight of both the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Olympic Council of Asia (OCA), whose authority in Olympic governance matters is final and determinative.

At the centre of the dispute lies the Financial Forensic Audit covering the period from 2015 to 2024. Subramaniam makes clear that proceeding with elections before the completion of this audit would constitute a breach of fiduciary duty, expose the NOCSL to reputational and regulatory risk, and potentially invite international sanctions. Any electoral outcome conducted amid unresolved allegations of fraud and financial mismanagement, he argues, would be legally vulnerable, procedurally defective, and devoid of domestic or international legitimacy.

Far from obstructing democratic process, Subramaniam frames the deferral of the AGM and elections as a legal necessity compelled by principles of natural justice, due process, and international compliance. To proceed otherwise, he contends, would amount to institutional negligence, effectively sanitizing unresolved misconduct and transferring authority to a new Executive Committee without first discharging accountability for past actions.

Importantly, Subramaniam underscores that his role is strictly transitional. Once the forensic audit is completed, responsibility apportioned, and corrective measures implemented, the constitutional pathway to an AGM and elections will be restored without impediment. Only then, he maintains, can governance be lawfully and ethically transferred to a successor body untainted by unresolved financial irregularities.

In legal terms, the confrontation is not a contest between rival office holders, but a question of compliance versus expediency. Subramaniam positions himself as the lawful custodian of the institution, acting under international mandate to safeguard the integrity of Sri Lanka’s Olympic movement until conditions for a valid, enforceable, and sanction-proof election are met.

Here Is How the Story Began: Jaswar Umar’s Accusations

At the heart of Umar’s challenge lies a single, pointed question: Who holds legal authority to govern Sri Lanka’s Olympic movement after the Executive Board’s term expired on 27 December 2025?

The Trigger: An Expired Mandate and a Legal Challenge

In an eight-page letter dated 28 December 2025, Jaswar Umar formally questioned the legitimacy of the continued functioning of the NOCSL Executive Board. Writing on behalf of the Football Federation and claiming the backing of a substantial majority of National Federations, Umar argued that the Board’s mandate automatically expired at midnight on 27 December.

According to Umar, any continuation in office without fresh elections or prior written approval from the IOC constitutes a direct violation of the Olympic Charter, particularly Rule 27, which enshrines democratic governance, autonomy, and athlete representation.

His letter was not framed as a political appeal but as a legal indictment.

Umar cited multiple provisions of both the Olympic Charter and the NOCSL Constitution to argue that there is no concept of implied or tacit extension of authority. In international sports law, he stressed, elected mandates terminate automatically unless exceptional circumstances justify an extension approved in advance by the IOC.

In Umar’s framing, the situation was unequivocal:

- The term expired

- No elections were held

- No prior IOC approval existed

- Therefore, the Board lacks legal authority

The Forensic Audit Argument: Justification or Red Herring?

The most contentious issue in the dispute is the ongoing forensic audit covering the period from January 2015 to December 2024.

Subramaniam had previously informed the General Assembly that the audit was the principal reason elections could not be conducted on schedule. Umar’s letter sought to dismantle that justification point by point.

According to Umar, a forensic audit is, by definition, an external corrective mechanism, not a governance suspension tool. He argued that international Olympic practice is clear: audits do not justify postponing elections or extending mandates. Governance continuity, he maintained, must be preserved through timely elections or IOC-approved interim arrangements.

More controversially, Umar raised the issue of conflict of interest, noting that six of the ten years under forensic scrutiny fell under Subramaniam’s presidency. In his view, continued involvement of office bearers whose conduct falls within the audit period creates both actual and perceived conflicts of interest.

In stark terms, Umar argued that no office bearer should facilitate or oversee an audit of their own period in power.

Allegations of Misrepresentation to the IOC

Perhaps the most explosive claim in Umar’s letter was the allegation that Subramaniam had written to the IOC seeking an extension of the Executive Board’s term without the mandate or consent of the General Assembly.

Umar characterised this communication as a misrepresentation of the institutional position of the NOCSL, arguing that while the IOC engages with institutions rather than individuals, any request affecting governance must originate from the General Assembly, the supreme authority of the NOCSL.

A unilateral request by the President, he warned, was constitutionally invalid and potentially exposed the NOCSL to sanctions under Rule 59 of the Olympic Charter.

The Demands: Step Aside and Stand Down

Umar concluded his letter with a series of blunt demands, calling on Subramaniam and the Immediate Past Executive Board to acknowledge that their term had expired and immediately refrain from:

- Performing functions as office bearers

- Using NOCSL premises, assets, or communication channels

- Issuing instructions to staff

- Representing the NOCSL domestically or internationally

Until guidance was received from the IOC, Umar urged the Board to cease all activity, framing this as necessary to protect the integrity and autonomy of Sri Lanka’s Olympic movement.

The Counterattack: Subramaniam Strikes Back

Subramaniam’s response, equally detailed and forceful, rejected Umar’s assertions in their entirety.

From the outset, he disputed Umar’s description of him as “Immediate Past President,” asserting instead that he remains the lawful President of the NOCSL. He accused Umar of acting maliciously, pursuing self-interested agendas, and attempting to derail ongoing reforms.

Subramaniam noted that Umar could not have been unaware of his communication to the General Assembly dated 22 December 2025, and argued that Umar’s decision to proceed regardless demonstrated bad faith and a deliberate attempt to create confusion.

He further confirmed that both the IOC and the OCA have formally directed that all official correspondence relating to the NOCSL be channelled exclusively through him. The OCA, he added, went further by advising that individuals facing corruption-related allegations should step aside from all current and future NOCSL activities.

Why Is Jaswar Umar Fighting This Battle?

Observers have questioned why the President of the Football Federation continues to contest the matter so vigorously, given that the NOCSL comprises multiple member sports associations beyond football.

However, critics argue that Umar’s resistance may be influenced by unresolved allegations raised in the past, including investigations conducted by the Special Investigation Unit for the Prevention of Offences Relating to Sport (SIU) in 2017 and a Five-Member Special Inquiry Committee appointed by the Ministry of Sports. Notably, the 2017 SIU investigation is reported to have recommended that Jaswar Umar be barred from holding office in any sports federation, a finding that, despite its seriousness, has never been acted upon. This has prompted further questions about why the current Minister of Sports, Sunil Kumara Gamage, appears reluctant to pursue enforcement action, and whether the findings of multi-member judicial and quasi-judicial bodies are being selectively disregarded.

That committee, ordered by former Sports Minister Roshan Ranasinghe and chaired by retired judge Sarojini Kusala Weerawardena, examined the constitution of the Football Federation, its financial controls, administration, sports promotion, and related matters. Although the committee produced extensive allegations, no charges were filed during 2021–2022, when Umar served as President of the FSL Executive Committee.

Umar has consistently maintained his innocence and publicly challenged critics to use available findings to charge him in court.

When contacted by The Morning Telegraph earlier, Umar said “I am not guilty of any of these findings.If I was then I would have been charged. Even now let anyone file these charges against me, I am confident I can defend myself in a court of law”.

Presidential Authority and IOC Protocol

Central to Subramaniam’s defense is Article 17 of the NOCSL Constitution, which designates the President as the legal representative of the Committee domestically and internationally.

He argues that IOC and OCA protocol recognizes communications only from the NOCSL President, and therefore his correspondence with the IOC did not require prior General Assembly approval. Any claim to the contrary, he warned, undermines institutional credibility and risks international standing.

A Different Reading of the Olympic Charter

Subramaniam rejects the notion of automatic expiry of authority, arguing that the Olympic Charter does not impose a rigid doctrine rendering an elected body functus officio when elections cannot be conducted due to exceptional circumstances.

Temporary continuation of administrative functions, he contends, is permissible when undertaken in good faith, with IOC knowledge, to preserve stability, compliance, and integrity.

He further argues that the forensic audit does not constitute external interference but rather aligns with global governance standards. Claims of Rule 27 or Rule 59 violations, he says, are premature and legally unsustainable.

Corruption, Resignations, and the Audit Backstory

Subramaniam detailed allegations involving former NOCSL office bearers, including resignations, suspensions, and bans affecting figures such as Maxwell De Silva, Kanchana Jayaratne, Suranjith Premadasa, Gamini Jayasinghe, Chandana Liyanage, and other former Executive Committee members.

He noted recent revelations that Kanchana Jayaratne is alleged to have received Rs. 5 million from the NOCSL for a forest project later rejected by Olympic Solidarity, despite objections from the Finance Committee Chairman. The project never materialized, and claims of bogus photographic evidence are currently under inquiry.

According to Subramaniam, past attempts to initiate a forensic audit were actively blocked by individuals now seeking a return to power. The audit, he insists, is a cleansing process—not a delaying tactic.

No Conflict of Interest, Says Subramaniam

Addressing conflict-of-interest allegations, Subramaniam stated that the audit is conducted independently and that he neither supervises nor controls it. His role, he said, is limited to responding transparently to auditor queries. Financial responsibility, he emphasised, rested with office bearers no longer in office.

A Battle with International Consequences

This dispute carries serious international implications. Precedents in India, Kuwait, Pakistan, Guatemala, and Sri Lanka itself show that governance failures can result in suspension, loss of funding, and athlete exclusion.

Subramaniam asserts that the IOC has endorsed his position and approved temporary continuation, rendering Umar’s challenge moot.

The Road Ahead

In summary, the balance of law, protocol, and institutional responsibility weighs in Subramaniam’s favour. His insistence on completing the forensic audit before elections is framed not as obstruction, but stewardship, an attempt to restore credibility in a sporting culture long damaged by mismanagement, fraud and corruption.

Sri Lanka’s Olympic history tells a stark story: since Duncan White’s silver medal in 1948 and Susanthika Jayasinghe’s silver in 2000, the nation has struggled to consistently qualify athletes for the Games.

Against that record, Subramaniam’s stand for clean governance offers a rare opportunity to rebuild the Olympic movement on foundations stronger than hope alone, on integrity, accountability, and fairness for athletes who deserve no less.