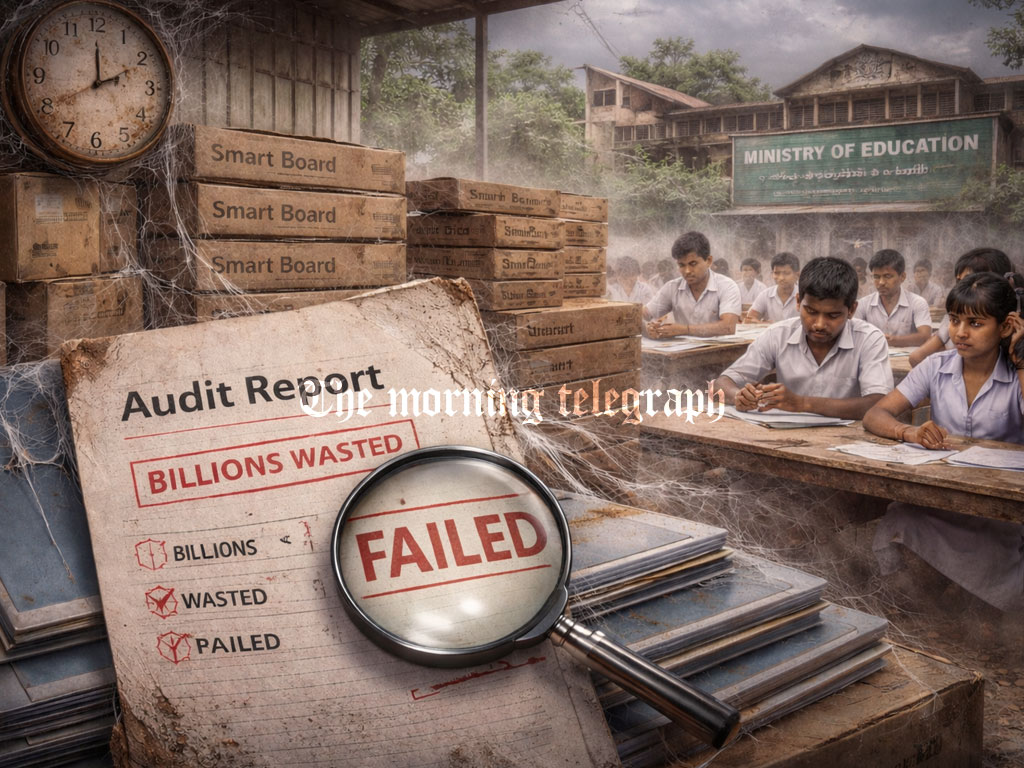

An explosive audit reveals how billions meant to transform Sri Lanka’s schools were swallowed by delays, failed planning, and unused technology, leaving students waiting until at least 2027 for promised reforms.

Sri Lanka’s long-promised education reform programme has stalled under the weight of repeated delays, controversial procurement decisions, and a widening gap between massive public spending and tangible classroom outcomes. A damning audit report reveals that more than five billion rupees were spent over three years on reforms that remain largely unimplemented, while expensive digital smart boards sit idle in government warehouses. With the government now delaying key reforms until 2027, the findings raise urgent questions about governance, accountability, and the future direction of Sri Lanka’s education system.

According to the audit, the former State Ministry of Education Reforms spent Rs. 5,219,297,390 between 2020 and 2022 to introduce sweeping changes to the national education framework. In addition, the National Institute of Education spent Rs. 350,552,393 on reform-related activities. Despite this substantial expenditure, the reforms were not delivered as planned. Much of the funding was sourced through loans from international lenders including the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, yet the promised improvements failed to materialize in schools. Auditors warned that continued failure to implement reforms could expose Sri Lanka to serious financial losses, especially at a time of economic strain, rising debt interest payments, and the risk of loan agreements being cancelled.

The reform effort itself was undermined by institutional instability and political disagreement. A dedicated State Ministry of Education Reforms was created by gazette notification to oversee the process, only to be abolished in July 2022. Its responsibilities were transferred back to the Ministry of Education, disrupting continuity and momentum. The audit notes that six core reform areas were identified and scheduled to begin in early 2021 under a five-year implementation plan. However, the ministry failed to complete these activities within the planned timeframe. Cabinet approval was granted only for curriculum and assessment reforms, while the remaining five reform areas proceeded without formal endorsement.

The absence of an approved national education policy further weakened the reform process. Although the National Education Commission submitted policy recommendations in 1992, 2003, 2016, and 2021, no national education policy had been approved as of September 30, 2025. This policy vacuum left reform initiatives without a coherent framework, undermining long-term planning and consistency. The audit also records that reforms initially scheduled for implementation this year have been postponed until 2027, reflecting deep political divisions over the future of Sri Lanka’s education system.

The most striking revelation in the audit concerns the procurement of 1,000 smart boards for schools at a cost of Rs. 149,351,069. Auditors describe the purchase as an emergency procurement carried out under false pretenses. Despite the absence of any genuine emergency, the Ministry of Education created an artificial sense of urgency to fast-track the purchase shortly before a presidential election. This decision has fuelled allegations of political manipulation, procedural abuse, and a lack of transparency in public procurement.

Compounding the issue, the audit reveals that the Ministry of Education failed to secure a promised grant of 500 smart boards from China, part of a wider $20 million assistance package. The Additional Secretary in charge of Information Technology and Digital Education proceeded with the purchase of 1,000 smart boards without securing the Chinese grant. By May 31 this year, no steps had been taken to obtain the promised equipment. Auditors found that the official leading the project was improperly appointed to the technical evaluation committee, in violation of procurement rules. The procurement timeline was shortened without justification, and technical specifications were added to bid documents without adequate review.

The smart boards were purchased through the Sri Lanka Government Commercial (Miscellaneous) Corporation, which initially submitted a higher cost estimate before revising the price after negotiations. Auditors also found that Cabinet was provided with misleading information, as the total project cost did not clearly disclose additional payments required to extend the warranty. The supplier had not agreed to a three-year warranty as stated in bid documents, and warranty extension costs were not properly documented in Cabinet submissions.

Despite plans to install the smart boards in 20 schools during the December 2024 school holidays, not a single unit was installed. An engineer brought in from abroad to supervise installation left the country without completing the task, leaving all 1,000 smart boards in storage at the Puttalagedera warehouse. The audit notes that many warranties have already expired or are close to expiring, further reducing the project’s viability. It also found that 121 of the selected schools lack fibre internet connectivity, a basic requirement for smart board use, and that no long-term operational plan was developed before importing the equipment.

Beyond the smart board failure, the audit highlights concerns over innovation labs. Although plans were announced to equip 750 schools with advanced technology, the labs remain non-operational. Despite this, the ministry purchased 3D printers and other high-tech equipment for 45 schools at a cost nearing Rs. 80 million, without conducting needs assessments or preparing implementation plans. Auditors criticized these purchases as lacking scientific and financial justification amid Sri Lanka’s economic constraints.

The report recommends holding senior officials accountable for financial losses if these projects cannot be implemented. Responsibility is placed on the Chief Accounting Officer of the Ministry of Education, the Additional Line Secretary for digital education, and members of the technical evaluation committee involved in the emergency procurement. The findings expose deeper governance failures, weak planning, and poor infrastructure assessment within the education sector.

As Sri Lanka struggles with economic recovery, the audit has alarmed educators, parents, and the public. With reforms delayed until 2027, students and teachers remain stuck in a system starved of meaningful change, while costly equipment gathers dust. The report underscores the urgent need for transparency, accountability, and strategic planning if future education reforms are to deliver real benefits to Sri Lanka’s classrooms.