Young accounting interns across Sri Lanka are speaking out about extreme working hours, low pay, and a silent system that treats exhaustion as a rite of passage rather than exploitation.

In Sri Lanka, accounting students enrolled in management faculties and professional bodies such as the Institute of Chartered Accountants are required to complete mandatory internships to qualify as professionals. These internships come with stipulated work-hour requirements depending on the qualification pathway, and trainees are officially entitled to a salary.

Yet behind the formal structure lies a harsh reality. Many interns say they are pushed into excessive workloads for minimal pay, often working late nights, weekends, and holidays with little regard for health, safety, or basic dignity.

The issue resurfaced sharply after the recent death of a young accounting trainee who was killed in an accident while returning home late at night after work. The incident reignited public debate over the intense work culture prevalent in accounting and audit firms.

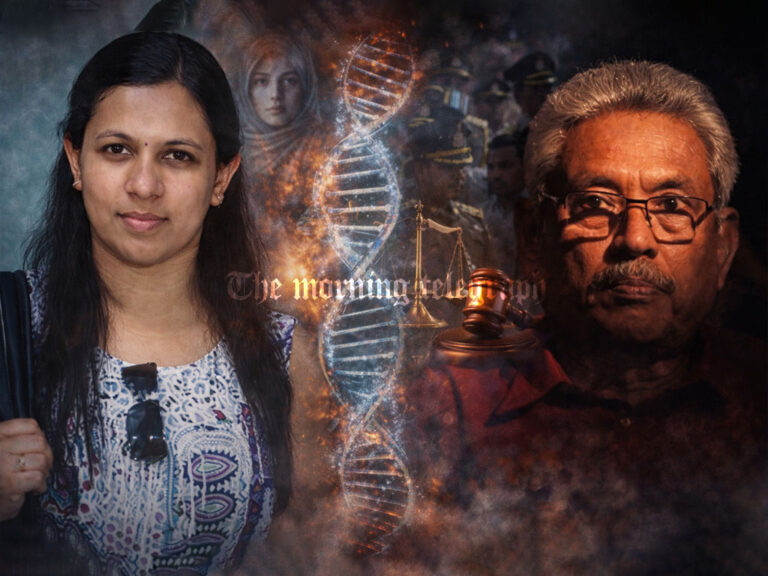

The discussion mirrors global concerns. In 2024, Anna Sebastian Peraille, a chartered accountant at Ernst and Young in India, died just four months into her job. Her death triggered a wave of testimonies on social media platforms, with professionals denouncing what many described as an “overwork culture” in large accounting firms.

Former trainees in Sri Lanka say their experiences are strikingly similar.

“I had to stay in the office for a week in the first month of my employment and work until dawn,” said Nishadi, not her real name. She explained that the busiest period in accounting firms typically runs from June to December, driven largely by tax filing deadlines.

Nishadi joined a firm during this peak season to complete her chartered accountancy training. From her first month, she found herself working continuously, often without leaving the office.

“From the beginning of September to the end of November, we had to stay in the office for most of the day. For a week straight, I worked in the office, carrying clothes, and there was a small washroom, but there was no shower to wash. I had to ask the tea maker in the office for a bucket and wash myself with difficulty. I slept in the board room,” she said.

She recalled filing tax returns at one or two in the morning when systems slowed down during peak hours. Despite the long days and nights, she said no overtime was paid.

“In addition to the 18,000 they were told to give me, I was not given anything even after working so much. Those who had worked for about a year were told to get 2,000. They had not received that either,” she said.

Her family struggled to understand why she remained at work overnight. “My family doesn’t understand. They ask why I stay in the office at night. They don’t understand even if I explain it to them,” she said.

Another former intern, Sandamali, also speaking under a pseudonym, said her firm refused to allow time off even for compulsory university assessments.

“I had to go to lectures and research work, but the management did not allow me to attend any of those things,” she said. “They did not even let me leave a little earlier. Most days I worked until about 11.30 pm.”

The pressure eventually made it impossible for her to complete her final academic thesis. One day, after working nearly 20 hours straight from 8 am until dawn, she decided to quit.

“I went home feeling like I was dead. That was the last day I went to work at that company,” she said.

Following the trainee’s death, the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka issued a statement expressing condolences and stating that it was reviewing measures to prevent similar incidents.

“The Institute acknowledges the concerns raised by our stakeholders regarding this tragic incident and assures that the circumstances are being reviewed with due care and seriousness,” the statement said.

However, the response drew sharp criticism online. “You keep increasing exam fees and renewals. But an audit trainee gets paid 12,500 for a month, working Saturdays and Sundays until they collapse,” one social media user commented.

According to official guidelines, each stage of professional qualification requires 220 working days. Yet trainees say the reality involves working day and night, including weekends and holidays, often without compensation.

“The partners and directors decide how long trainees work and how much they are paid,” one accountant said. “But they live by entirely different rules.”