Forty years after a brutal killing sent shockwaves through Sri Lanka’s political landscape, the full story of clandestine networks, cross ethnic alliances, and the paranoia that consumed a generation finally emerges from the shadows.

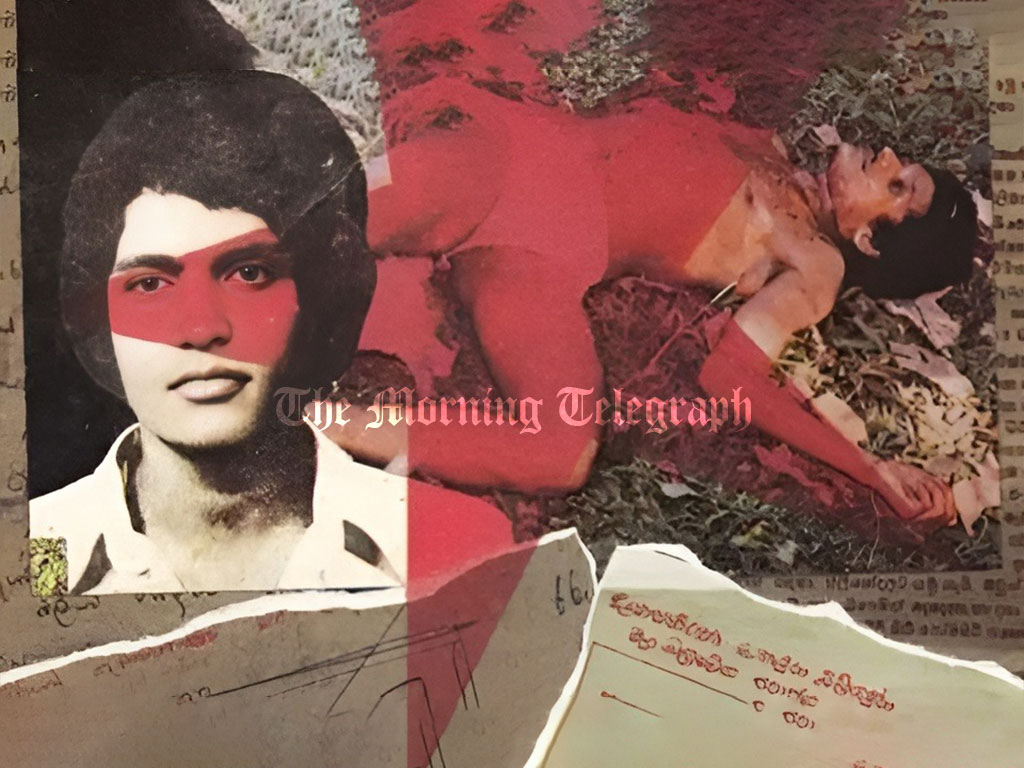

The cigarette smoke had barely dissipated from the rooms where student leaders plotted revolution when the knife found Daya Pathirana. December 15, 1986, marked a turning point in Sri Lanka’s turbulent history. The day the Socialist Students Union, affiliated with the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, eliminated the third leader of the Independent Student Union. His body was discovered at Hirana, Panadura, bearing the unmistakable marks of political vengeance. His associate, Punchiralalage Somasiri, survived the attack against overwhelming odds, left to carry both scars and secrets for decades to come.

Dharman Wickremaratne, a veteran journalist who once wrote for Divaina, has spent two decades piecing together fragments of this violent history. His latest work, “Daya Pathirana Guhathanaye Nodutu Petha” (The Unseen Side of Daya Pathirana Killing), represents the fifth installment in a series examining the two ill fated insurgencies launched by the JVP in 1971 and the early 1980s. What makes this account particularly valuable is the unprecedented access Wickremaratne secured from individuals who operated within both the SSU and ISU, including the miraculously surviving Somasiri himself.

The Independent Student Union had evolved through several leaders before Pathirana’s tenure. Deepthi Lamahewa served as its inaugural leader, followed by Warmakulasooriya, before Pathirana assumed leadership. After his killing, K.L. Dharmasiri took command, himself destined to fall to SSU violence three years later. The cyclical nature of revolutionary violence becomes painfully evident in this succession. Those who wielded the knife eventually felt its edge.

Wickremaratne justified Daya Pathirana’s killing on the basis that those who believed in violence did by it, a philosophical observation that neither excuses nor condemns but merely acknowledges the brutal logic that governed revolutionary movements during this period.

Wickremaratne’s narrative takes readers into uncharted territory, revealing connections between southern university students and northern militant groups that predated the cataclysmic July 1983 violence. The LTTE killing of thirteen soldiers and an officer at Thinnavely, Jaffna, triggered widespread anti Tamil pogroms, but the groundwork for cross ethnic collaboration had already been laid in university common rooms and safe houses across Colombo.

While the LTTE eventually emerged as the dominant Tamil militant organization, other groups including the People’s Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam maintained active operations. The JRJ government’s response to escalating northern violence involved transferring police and military resources away from the south, creating space for new alliances to flourish. Within this vacuum, the ISU developed increasingly close ties with PLOTE, connections that Wickremaratne argues have never received adequate public scrutiny.

The Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students also maintained involvement with the ISU. According to the author’s research, the ISU held its inaugural meeting on April 10, 1980, and within a year had established contact with the Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front. These relationships would prove fateful for Pathirana and several of his associates.

The SSU’s investigation into ISU activities grew increasingly intensive as suspicions mounted about direct involvement in Tamil militant operations. Wickremaratne reveals how ISU activist Pradeep Udayakumara Thenuwara was forcibly transported to Sri Jayewardenepura University, where SSU members subjected him to rigorous interrogation regarding a high profile PLOTE operation. The information extracted during such sessions contributed to the growing case against Pathirana.

The Nikaweratiya attacks on April 26, 1985, proved particularly significant in sealing Pathirana’s fate. A sixteen member gang simultaneously struck the Police Station and the People’s Bank branch. The SSU came to believe that two of these operatives belonged to the ISU. Pathirana himself and another individual identified as Thalathu Oya Seneviratne, known as Captain Senevi. Intelligence regarding ISU involvement reached the SSU through Nagalingam Manikkadasan, a PLOTE cadre whose Sinhalese mother maintained family connections with JVP leader Upatissa Gamanayake.

Manikkadasan’s own story illustrates the dangerous intersections of this period. Wickremaratne met him at Bambalapitiya in the company of Dharmalingham Siddharthan, during the period when PLOTE supported President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s administration. The LTTE would eventually kill Manikkadasan in a September 1999 bomb attack on a PLOTE office in Vavuniya, adding another name to the long list of those consumed by the violence they helped perpetuate.

President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s role in bringing Tamil militant groups into the political mainstream represents another contentious aspect of this history. Despite advisors expressing concern about his negotiations with the LTTE, Premadasa directed Elections Commissioner Chandrananda de Silva to grant political recognition to the LTTE’s political wing, the People’s Front of Liberation Tigers. This recognition came in early December 1989, merely seven months before Eelam War II erupted, demonstrating the profound miscalculations that characterized political engagement with militant groups.

Transformation of ISU

The transformation of the ISU from a student organization into an active participant in counter insurgency operations represents one of the most troubling aspects of this narrative. As the JVP insurgency intensified, the ISU became integrated into the UNP government’s bloody response. Some members eventually received payments through the National Guard program, with the government raising no objections to this arrangement.

Wickremaratne documents the operation of torture chambers at Colombo University’s Law Faculty and the Yataro operations center at Havelock Town, emphasizing the ISU’s direct involvement in running these facilities. Major Tuan Nizam Muthaliff, who commanded the Yataro facility near State Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne’s residence, is widely believed to have shot JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera in November 1989. Muthaliff himself fell to LTTE assassins on May 3, 2005, at Polhengoda junction, Narahenpita, while serving in Military Intelligence.

Somasiri, who was abducted along with Pathirana at Thunmulla and attacked with the same specialized knife but survived, represents a living connection to this violent history. His subsequent political evolution illustrates the diverse paths taken by those who navigated this period. Somasiri contested the May 6 Local Government elections on the Jana Aragala Sandhanaya ticket, a front organization of the Frontline Socialist Party that broke away from the JVP in April 2012. This group also played a critical role in the violent protest campaign Aragalaya against President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who was forced from office in July 2022 despite securing 6.9 million votes at the 2019 presidential election.

The electoral fortunes of groups claiming revolutionary lineage remain mixed. Jana Aragala Sandhanaya contested 154 Local Government bodies but secured only sixteen seats, while the ruling party JVP comfortably won the vast majority of Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas. These outcomes suggest limited public appetite for revolutionary nostalgia.

Premadasa SSU/JVP link

The book launch event in Colombo featured a provocative address by Gevindu Cumaratunga, former lawmaker and Jathika Chintanaya Kandayama stalwart. Cumaratunga drew parallels between Pathirana’s killing and the recent death of Nandana Gunatilleke, questioning the circumstances surrounding both incidents. He emphasized that assassination should never become a political tool, regardless of the objectives sought.

Cumaratunga recalled the false accusations directed at UNPer Gamini Lokuge regarding the 1986 killing, alleging that the SSU attempted to deflect blame onto others after carrying out the murder. He praised Wickremaratne for naming the SSU hit team and for providing comprehensive media coverage to student movements, particularly those based at Colombo University.

The audience at the book launch grew restless as Cumaratunga directed criticism toward the JVP led Jathika Jana Balawegaya and strategist Professor Nirmal Dewasiri, who had been associated with the SSU during the turbulent period. Cumaratunga recounted attending Pathirana’s funeral in Matara despite fearing potential retaliation, highlighting the climate of terror that prevailed.

Perhaps the most explosive allegation concerned Ranasinghe Premadasa’s alleged connections with the SSU. Cumaratunga reminded listeners that the SSU continued anti JRJ campaigns even after the UNP named Premadasa as their presidential candidate for December 1988. His implication was clear. Premadasa had reached an understanding with the SSU before securing nomination, fearing that JRJ might instead choose Gamini Dissanayake or Lalith Athulathmudali.

The appearance of anti Premadasa posters at Colombo University sparked intense discussions within the SSU. Premadasa expressed public surprise at these posters appearing alongside his own “Me Kawuda” campaign, promising parliamentary inquiry into the matter. According to Cumaratunga, UNP operatives entered the university that very night to remove the offending posters, suggesting coordination that contradicted public denials.

Cumaratunga asserted with confidence that the SSU supported Premadasa’s presidential bid, suggesting that the UNP leader might not have prevailed without their backing. This raises profound questions about one of the bloodiest elections in post independence history and the clandestine alliances that shaped its outcome.

The speaker also addressed Anupa Pasqual, his former comrade who later switched allegiance to Ranil Wickremesinghe after Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s ouster. While criticizing this political migration, Cumaratunga acknowledged Pasqual’s courage as a student leader during dangerous times, demonstrating the complex judgments required when assessing individuals who navigated this period.

SSU accepts Eelam

The Viplawadi Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, also known as the Revolutionary Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna or Vikalpa Kandaya, maintained particularly interesting relationships with Tamil groups. Both the Alternative Group and ISU participated in joint campaigns with Tamil militants, receiving weapons training from PLOTE and EPRLF both in Sri Lanka and India. This collaboration occurred in the period preceding the Indo Lanka Peace Accord, and significantly, involved acceptance of Tamil rights to self determination. A position that would later prove controversial within Sinhala political discourse.

Dharmeratnam Sivaram, later known by the pen name Taraki, maintained direct contact with ISU and arranged weapons training for its members. PLOTE Chief Uma Maheswaran personally informed the author that his organization provided free weapons training to ISU members while charging the JVP for similar services. This distinction in treatment suggests differing assessments of the two organizations’ revolutionary potential or trustworthiness.

Sivaram’s later career as a journalist writing for The Island and other publications saw him propagate views emphasizing that military means alone could not resolve the ethnic conflict. His abduction near Bambalapitiya Police Station on April 28, 2005, and the discovery of his body the following day, silenced a distinctive voice in Sri Lankan journalism. The LTTE posthumously conferred their highest civilian honor, the Maamanithar title, upon him.

India’s role in distributing weapons to Tamil militant groups during this period raises uncomfortable questions about sovereignty and regional interference. These groups subsequently trained Sinhala youth, creating networks that would influence southern politics for decades. Whether this formed part of a broader Indian destabilization project directed at Sri Lanka remains inadequately examined by official inquiries. PLOTE and EPRLF could not have operated training camps in India without that government’s knowledge, yet Sri Lanka never systematically investigated the origins of terrorism or identified those who propagated separatist ideologies.

Exactly one year before Pathirana’s killing, the ISU had arranged to dispatch a fifteen member group to India for training. Authorities aborted this operation after apprehending individuals who had previously received weapons training in India, demonstrating the security apparatus possessed some intelligence about these networks but failed to dismantle them comprehensively.

Wickremaratne’s narrative, while focused on Colombo University, illuminates broader patterns of Indian destabilization that might have triggered equally destructive conflict in the south. In a tragic irony, Pathirana’s killing may have preempted wider conflict, eliminating a figure whose cross ethnic collaborations threatened both the JVP’s revolutionary purity and the state’s stability.

Cumaratunga’s entry into politics was itself catalyzed by Pathirana’s activities. Entering Colombo University with little political interest, he found himself compelled to counter the separatist arguments promoted by the ISU strongman. Pathirana, perpetually clutching a cigarette, warned the young Cumaratunga of dire consequences should he persist with opposing views. This personal dimension adds texture to the political narrative, reminding readers that ideological conflicts manifested in face to face confrontations between individuals who shared campus spaces and common rooms.

The book launch unfortunately failed to generate the anticipated public dialogue about this period. Wickremaratne observed that when the SSU decided to eliminate Pathirana, they received tacit support from student factions affiliated with other political parties, including the UNP. This convergence of interests across ideological lines demonstrates how Pathirana’s cross ethnic collaborations had alienated him from the nationalist mainstream across the political spectrum.

Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s assumption of JVP leadership from Somawansa Amarasinghe in December 2014 brought important acknowledgments of past violence. In an interview with Saroj Pathirana, Dissanayake not only expressed regret but requested forgiveness for approximately six thousand killings perpetrated by the party during the second insurgency. This public reckoning represented a significant departure from previous JVP positions, though critics questioned whether acknowledgment alone sufficed.

Wickremaratne strategically utilized Frontline Socialist Party leader Kumar Gunaratnam’s November 2019 interview with Upul Shantha Sannasgala to remind readers that Gunaratnam himself remained with the JVP when the decision to eliminate Pathirana was taken. Gunaratnam’s departure from the JVP in April 2012 followed years of internal turmoil, yet his presence during that fateful decision remains historically significant. Wimal Weerawansa and Nandana Gunatilleke led another faction that supported President Mahinda Rajapaksa during his first term while maintaining party connections. These various splinters from the original JVP tree cannot escape the moral implications of violence perpetrated during 1980 to 1990, regardless of subsequent political positioning.

This principle applies equally to JVP members now operating within the Jathika Jana Balawegaya, formed in July 2019 to create a presidential platform for Dissanayake. At that election, Dissanayake secured third place with 418,553 votes representing 3.16 percent of ballots cast. A distant result that would transform dramatically in subsequent years.

Examining JVP terrorism requires contextual understanding of JRJ’s political strategy for suppressing opposition. The December 1982 referendum, marred by violence and irregularities, enabled JRJ to postpone parliamentary elections scheduled for August 1983. Fearing loss of parliamentary supermajority, JRJ imposed this undemocratic solution. Sri Lanka’s only referendum conducted to delay an election. On July 30, 1983, JRJ proscribed the JVP alongside the Nava Sama Samaja Party and Communist Party, falsely claiming they orchestrated attacks on Tamil communities following the Jaffna soldier killings.

Under Dissanayake’s leadership, the JVP underwent comprehensive transformation, though Somawansa Amarasinghe initiated this evolution. Amarasinghe made the controversial decision to support war winning Army Chief General Sarath Fonseka at the 2010 presidential election. A choice comparable in significance to launching the second insurgency against JRJ’s provocations. This alignment with the UNP and Tamil National Alliance, historically an LTTE ally, failed in 2010 but succeeded at the 2015 presidential election when Maithripala Sirisena emerged victorious.

The post Indo Lanka Peace Accord period, particularly the July 1987 induction of the Indian Army, provided opportunity for JVP campaign intensification. The August 1987 hand grenade attack on the UNP parliamentary group killed Matara District MP Keerthi Abeywickrema and staffer Nober Seneadeera, wounding sixteen others. Both President JRJ and Prime Minister Premadasa were present when the two grenades landed among the parliamentary group. Had this assassination plot succeeded, Sri Lanka’s trajectory would have altered dramatically.

Cumaratunga’s speech posed a provocative hypothetical: where would Daya Pathirana stand today had he survived that December night? This question acknowledges the unpredictable transformations that political actors undergo across decades. Some ISU members eventually joined civil society organizations; others entered electoral politics through various coalitions. Somasiri, who survived the attack that killed Pathirana, contested local government elections on the Jana Aragala Sandhanaya ticket, a Frontline Socialist Party front organization that also participated in the Aragalaya campaign against President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. That campaign succeeded in forcing the wartime Defence Secretary, who won the 2019 presidency with 6.9 million votes, to flee the country in July 2022.

The 2023 local government elections demonstrated the political marginalization of groups claiming continuity with revolutionary traditions. Jana Aragala Sandhanaya contested 154 local bodies but secured only sixteen seats, while the JVP comfortably won most Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas. These electoral outcomes suggest that while revolutionary violence shaped Sri Lanka’s political development, its direct practitioners struggle to translate historical significance into contemporary electoral success.

Wickremaratne’s five volume examination of JVP insurgencies represents an important contribution to understanding Sri Lanka’s political violence. His latest work, focusing on previously unexplored connections between southern students and northern militants, challenges comfortable narratives that separate the ethnic conflict from southern political developments. The ISU PLOTE EROS EPRLF nexus reveals that cross ethnic collaboration extended beyond rhetorical solidarity into operational military cooperation, with weapons and training flowing through networks that transcended ethnic boundaries.

The Pathirana killing also illuminates the intersection of revolutionary violence with state counter insurgency. ISU members who survived JVP attacks sometimes found themselves integrated into government security operations, receiving payments and protection in exchange for intelligence and operational support. This co optation blurred lines between revolutionary and counter revolutionary violence, creating ambiguities that persist in contemporary political alignments.

Wickremaratne’s methodology deserves acknowledgment. Securing cooperation from individuals who participated in these events, including those who ordered killings and those who escaped death, required persistence and credibility developed over two decades of investigation. His subjects clearly trusted him with information that could incriminate them or their former comrades, suggesting careful cultivation of relationships and guarantees of responsible use.

The resulting narrative provides texture often missing from academic accounts of this period. We learn not only about political maneuvers but about personalities, about the cigarette perpetually dangling from Pathirana’s fingers, about the specialized knife used in his killing, about the specific locations where torture occurred. These details transform abstract political history into visceral human experience.

Somasiri’s survival functions almost as a narrative device throughout the book. The witness who lived to tell, who carries both physical scars and institutional memory. His participation in recent electoral politics demonstrates continuity between past violence and present political engagement, though the Frontline Socialist Party’s poor electoral performance suggests limited appetite among voters for revolutionary nostalgia.

The Manikkadasan thread illustrates how familial connections transcended ethnic boundaries even as political violence intensified. With a Sinhalese mother related to JVP leadership, Manikkadasan occupied an ambiguous position that enabled him to transmit intelligence across organizational lines. His eventual death in LTTE bombing demonstrates that such ambiguous positions became untenable as conflict polarised.

Muthaliff’s trajectory from Yataro facility commander to Military Intelligence officer to LTTE assassination victim similarly illustrates the dangerous pathways carved by those who participated in this violence. Credited with killing Wijeweera, Muthaliff himself fell to LTTE guns two decades later, suggesting that revolutionary violence operates on timelines extending far beyond immediate conflicts.

The question of Indian involvement in training Sinhala youth through Tamil militant intermediaries remains inadequately addressed in official discourse. Wickremaratne’s documentation of these networks, corroborated by Uma Maheswaran’s admissions, suggests systematic Indian engagement with southern political actors that extended well beyond the ethnic conflict. Whether this represented rogue elements within Indian intelligence or coordinated policy remains unclear, but the existence of such engagement is now well documented.

Taraki’s transformation from militant trainer to influential journalist illustrates the intellectual continuity underlying political violence. His arguments that military means alone could not resolve the ethnic conflict, published in mainstream English newspapers, influenced elite opinion while his revolutionary past remained largely unknown to readers. The LTTE’s posthumous honor recognized his contributions to their cause, even as he wrote under a pseudonym for Sinhala readers.

The book launch audience’s interruption of Cumaratunga’s remarks about Professor Nirmal Dewasiri suggests continued sensitivity about individual roles during this period. Dewasiri, now a prominent JVP strategist, maintains institutional continuity with the organization that ordered Pathirana’s killing. Whether individual responsibility attenuates across decades or remains attached to persons regardless of subsequent evolution remains contested among those who lived through this period.

Cumaratunga’s allegation that Premadasa could not have won without SSU support, if accurate, would fundamentally revise understanding of Sri Lanka’s political development. The 1988 presidential election occurred amid extraordinary violence, with both JVP and government forces conducting operations that claimed thousands of lives. If the SSU indeed directed its considerable organizational capacity toward Premadasa’s election, this represents a political accommodation with profound implications for understanding both Premadasa’s presidency and JVP strategy.

The transformation of ISU members into government paid National Guard members represents another dimension of this accommodation. Revolutionary students who trained with Tamil militants in Indian camps eventually received state salaries to participate in counter insurgency operations against their former ideological comrades. Such transformations demonstrate the fluidity of political commitment during periods of intense violence.

Wickremaratne’s account of torture facilities at Colombo University’s Law Faculty and Yataro implicates ISU members directly in state violence against JVP suspects. This complicates any simple narrative of revolutionary purity confronting state oppression. Both sides employed methods that violated basic human dignity, and individuals moved between categories as circumstances shifted.

The Pathirana killing thus emerges from Wickremaratne’s account not as simple revolutionary justice against a traitor, but as a complex event situated within multiple overlapping conflicts. Between JVP and state, between Sinhala and Tamil nationalisms, between competing revolutionary organizations, and between individuals whose relationships combined ideological commitment with personal animosity.

Cumaratunga’s insistence that assassinations should never become political tools seems almost naive given the prevalence of such methods throughout Sri Lanka’s post independence history. Yet his point deserves consideration: when political differences are settled through violence, the possibility of democratic resolution recedes. Pathirana’s killing resolved nothing permanently. It merely removed one actor from a stage crowded with others equally committed to violent methods.

The question of whether Pathirana would have evolved politically had he survived, raised by Cumaratunga, acknowledges that individuals change across decades. Some ISU members became civil society activists; others entered parliamentary politics through various coalitions. Pathirana’s death foreclosed whatever evolution he might have undergone, freezing him permanently as the revolutionary martyr or traitor, depending on perspective.

Wickremaratne’s achievement lies in restoring complexity to this history without endorsing the violence he documents. His sources include perpetrators and victims, those who ordered killings and those who escaped them, those who remained consistent in their commitments and those who transformed entirely. This multiplicity of perspectives prevents any simple moral accounting while acknowledging that moral judgments remain necessary.

The forty year distance from Pathirana’s killing enables reflection that was impossible in 1986. Sri Lanka has experienced civil war, foreign intervention, tsunami, economic collapse, and popular insurrection since that December night. The political landscape has transformed almost beyond recognition, yet the networks established during that period continue influencing contemporary alignments.

JVP members who ordered Pathirana’s killing now govern through Jathika Jana Balawegaya, having achieved electoral success that eluded their revolutionary predecessors. Former ISU members sit in parliament through various coalitions. Some who trained with PLOTE now advocate for Sinhala nationalist positions. These transformations demonstrate that revolutionary commitments rarely survive contact with electoral politics and institutional power.

Wickremaratne’s book joins a growing literature examining Sri Lanka’s political violence with increasing honesty and complexity. The passage of time enables investigation that was impossible when participants feared prosecution or revenge. Witnesses who remained silent for decades now share their experiences, contributing to historical understanding even as they acknowledge their own complicities.

The Pathirana killing will never receive judicial resolution. Too many participants have died, too much evidence has disappeared, too many political interests prefer historical ambiguity. But Wickremaratne’s documentation ensures that the event cannot simply disappear from historical memory. Future generations will have access to accounts that name names, specify locations, and trace connections that official narratives prefer to obscure.

This historical work matters because Sri Lanka continues grappling with questions first posed during the period Wickremaratne examines. How should the state respond to armed insurrection? What relationships between ethnic communities are possible after civil war? Can revolutionary movements transform into democratic political parties without betraying their foundational commitments? These questions lack easy answers, but understanding how previous generations addressed them provides context for contemporary debates.

The cigarette smoke has long dispersed from the rooms where Pathirana plotted with PLOTE operatives, where SSU members interrogated suspects, where decisions about life and death were made with casual certainty. But the institutional patterns established during that period persist, encoded in organizational cultures and personal relationships that span decades. Understanding these patterns requires engagement with history that Wickremaratne’s work enables.

His willingness to name names, to specify locations, to trace connections that others prefer to forget, represents scholarly courage. Sri Lanka remains a society where historical reckoning often yields to political convenience, where uncomfortable truths are buried beneath nationalist narratives. Wickremaratne’s excavation of these truths serves the cause of genuine historical understanding, whatever discomfort it causes among those who prefer ambiguity.

The Pathirana killing thus stands as both specific event and representative symbol. A moment when revolutionary violence turned inward, consuming those who had dedicated their lives to political transformation. Its lessons extend beyond Sri Lanka to all societies where political differences are settled through assassination rather than debate. The cigarette smoke clears, the knife finds its target, and history moves on, leaving only questions about what might have been.