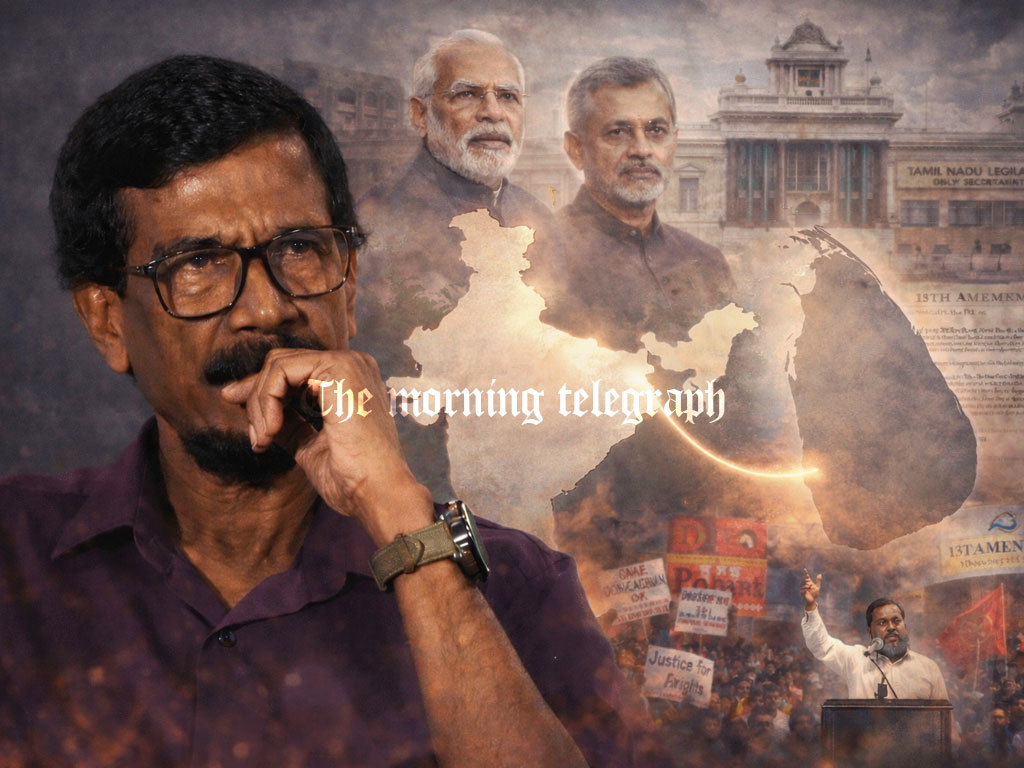

From Delhi’s diplomatic corridors to Tamil Nadu’s economic transformation, Tilvin Silva’s India visit has reignited debate over devolution, Provincial Council elections, and whether Sri Lanka will embrace power sharing as a national development strategy or retreat into old ideological battles.

At the heart of Sri Lanka’s evolving political landscape lies a pressing and timely question: what did Mr. Tilvin Silva truly learn from India? As General Secretary of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna JVP, Silva’s first official visit to India was not a routine diplomatic tour. Conducted under the Indian Council for Cultural Relations ICCR Distinguished Visitors Programme from 5 to 12 February 2026, the visit carried layered symbolic and strategic significance. It unfolded at a moment when Sri Lanka’s governance model, provincial devolution framework, and national reconciliation agenda remain intensely debated.

During his stay, Silva held high level discussions with India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar. He also toured Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh, two states often cited as emblematic of India’s economic modernization, technological innovation, and federal governance model. These engagements exposed him to a version of India that foregrounds infrastructure growth, digital transformation, and provincial empowerment. His reflections suggested a nuanced perspective. On one side, he acknowledged that India’s national focus appears firmly anchored in development and innovation rather than in exerting political pressure to force Sri Lanka toward long delayed Provincial Council elections.

On the other hand, Silva’s comparative remarks about India and China opened a deeper debate about development models and governance structures. He observed: “In India, we see that though there are efforts to introduce new technology, there have been some obstacles in implementing these initiatives because there are religious and cultural practices and traditions that have to be navigated. In China, it is not like that.” That candid comparison raised broader questions about whether Sri Lanka should pursue a pluralist democratic framework or a centralized, efficiency driven model.

Silva’s position on Provincial Council elections remains carefully balanced. When the Tamil question surfaced during his discussions in India, he stressed that he was present in his capacity as JVP General Secretary, representing the party rather than the Sri Lankan government. Yet his longstanding critique of the provincial council system as structurally flawed complicates matters. This duality invites scrutiny. Are his comments reflective of evolving party ideology, or do they signal a broader recalibration of government policy under the JVP led National People’s Power NPP?

The larger issue extends beyond allegations of Indian pressure. The real test is whether Sri Lanka would independently proceed with Provincial Council elections in the absence of external encouragement. Silva has argued that if the JVP intends to function as a responsible government, it must ensure democratic processes and balanced economic development across all provinces. That assertion aligns with global democratic norms but leaves unanswered questions about institutional reform and constitutional commitment.

India’s stance on devolution and the 13th Amendment remains consistent. As Dr. S. Jaishankar articulated in 2021: “It is in Sri Lanka’s own interest that the expectations of the Tamil people for equality, justice, peace, and dignity within a united Sri Lanka are fulfilled. That applies equally to the commitments made by the Sri Lankan Government on meaningful devolution, including the 13th Amendment.” This statement underscores India’s view that devolution is not merely a bilateral issue but a matter of Sri Lanka’s internal stability and inclusive governance.

New Delhi insists that its position is not a proxy for Tamil political demands but reflects the responsibility of a neighboring nation with over 85 million Tamil speakers in South India. From India’s perspective, safeguarding Tamil rights within a united Sri Lanka enhances regional stability and strengthens bilateral relations. This framing challenges narratives that portray Indian involvement as interference.

Within Sri Lanka, Tamil political parties have repeatedly appealed to India when domestic avenues appeared stalled. Their appeals mirror a persistent political reality. When Colombo hesitates on devolution or election commitments, Tamil leaders seek diplomatic reinforcement from New Delhi. Prime Minister Modi’s recent visit to Colombo revived these calls, with Tamil representatives urging Indian support for Provincial Council elections as part of meaningful power sharing.

Critics of devolution often interpret India’s engagement through a nationalist lens. Yet the historical record indicates that Tamil parties have consistently sought external advocacy because of perceived inaction in Colombo. This dynamic has fueled suspicions that the JVP led NPP might eventually attempt to abolish the provincial council system entirely. Such suspicions draw strength from the JVP’s past opposition to devolution, which escalated into violence, including assassinations of supporters of the 13th Amendment during earlier political phases.

Tamil leaders recently met Dr. Jaishankar in Colombo, reiterating their demand for elections. Their appeals were directed at India but also at Silva, whose arrival in New Delhi was anticipated as part of a broader political recalibration.

The JVP characterizes its current phase as the third stage of its political evolution. Analysts frequently distinguish between JVP1, JVP2, and the present iteration. JVP2 was marked by Marxist rhetoric, Sinhala nationalist narratives, and pronounced anti Indian sentiment. Silva himself conceded that ideological change is necessary. He remarked: “I explained to officials at the Indian High Commission that this opinion needs to change. We still have the ‘five classes’ in our political education, but there is none about India specifically.” That admission signals an awareness of outdated doctrinal frameworks.

Yet history complicates reinvention. The party once opposed the Indo Lanka Accord and labeled Indian origin Tamils as a fifth column instrument of Indian expansionism. If both India and the JVP claim to have evolved, the logical question follows. Why resist a provincial governance model inspired by India’s federal architecture?

India’s federal system provides instructive precedents. Tamil Nadu’s political trajectory illustrates the transformative potential of devolution. In the 1930s, E.V. Ramasamy Periyar advocated separation. His disciple C.N. Annadurai carried that rhetoric into electoral politics. However, by 1967, amid geopolitical shifts following the Sino Indian war and constitutional changes such as the 16th Amendment, separatism receded.

Today Tamil Nadu stands as India’s second largest economy, often cited as a benchmark for industrial growth, human development indicators, and regional innovation. The so called Tamil Nadu model reflects the effectiveness of provincial autonomy within a unified state. Economic dynamism replaced secessionist sentiment.

The evolution of Tamil Nadu demonstrates that power sharing can strengthen national unity rather than weaken it. The once popular slogan that the North flourishes while the South wanes has lost relevance. Regional empowerment delivered inclusive growth, infrastructure expansion, and social mobility. Federal governance proved compatible with national integrity.

For Sri Lanka, these lessons carry weight. A durable political settlement requires enabling provinces beyond the Western Province to participate meaningfully in economic development. Devolution should not be framed exclusively as a Tamil grievance but as a comprehensive national development strategy that enhances accountability, local governance, and regional equity.

India’s model is rooted not in ethnicity or religious preference but in constitutional federalism and inclusive growth. For a multilingual democracy like Sri Lanka, structured power sharing may offer a path toward stability, reconciliation, and balanced economic progress. In contrast, highly centralized or authoritarian systems promise efficiency but often suppress pluralism and local representation.

Tilvin Silva’s India visit thus becomes more than a diplomatic courtesy. It symbolizes a crossroads. Will Sri Lanka reinterpret devolution as a catalyst for development, or will ideological inertia stall reform? The answer may shape not only Provincial Council elections but also the country’s broader economic trajectory and democratic credibility.

India’s federal experience, with all its imperfections and complexities, suggests that unity and diversity need not be mutually exclusive. The real lesson may lie not in choosing between India and China, but in recognizing that inclusive governance anchored in constitutional commitment can deliver long term national prosperity.