There’s an invisible force surrounding us every day one that we rarely pay attention to, but that is slowly and relentlessly cutting short our lives. It’s not a new disease, nor a toxic chemical, but something far more common, far more underestimated.

It’s noise.

Noise doesn’t just harm our ears. It disrupts our bodies, raises our stress levels, and according to mounting evidence, it’s contributing to major health conditions like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and even dementia.

“It’s a public health crisis,” says Professor Charlotte Clarke from St George’s, University of London. “Many people are exposed to it in their daily lives.” And yet, it’s a crisis that goes unnoticed by most.

To better understand the effects, I set out to explore the moment noise begins to harm the human body. I began by visiting people suffering from noise-induced health issues and asked whether they felt any escape from our increasingly loud world.

In a silent laboratory, I met Professor Clarke. The room was eerily quiet so much so that the silence itself felt almost oppressive. I wore a smartwatch-like device that monitored my heart rate and sweat levels while listening to various sounds.

With headphones on, I immersed myself in everyday noises.

One sound disturbed me the most the relentless traffic of Dhaka, Bangladesh, one of the world’s noisiest cities. Within seconds, I felt like I was trapped in a massive traffic jam. My stress level soared, and my body responded my heart rate rose, and I began sweating more.

“There’s good evidence that traffic noise can affect your heart health,” Professor Clarke said as she prepared the next sound.

What finally soothed me wasn’t silence, but the distant laughter of children at play. However, familiar noises like barking dogs and noisy neighbors triggered stress again.

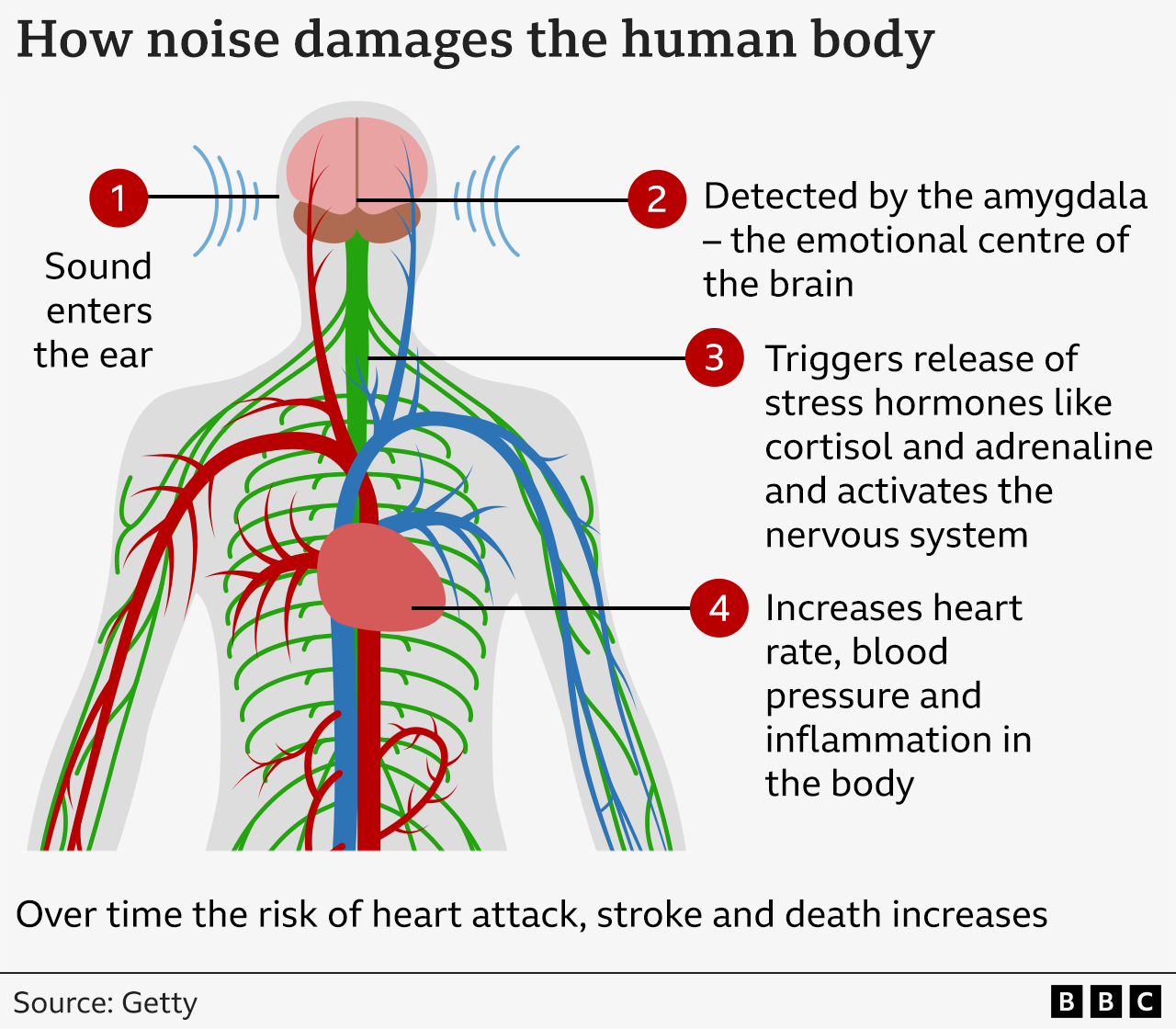

So why does sound affect our body so deeply?

“You respond to sound emotionally,” Clarke explains.

Sounds are processed in our ears, sent to our brain, where the amygdala our emotional processor makes a quick judgment. It’s the part of the brain involved in fear and survival responses. It evolved to help us react swiftly to threats—like a predator moving through the forest.

“That’s why your heart rate increases, your nervous system reacts, and stress hormones are released,” says Clarke.

In an actual emergency, that reaction can be life-saving. But over time, when experienced continuously, it damages the body.

“Your body responds constantly if you’re exposed for years. That persistent stress response increases the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes,” Clarke says.

What’s alarming is this can happen without us realizing it even while we’re asleep. Many believe they’ve adapted to city noise, like the hum of planes overhead or nearby highways. But Clarke explains the body never truly adapts.

“You never close your ears. Even while you sleep, your brain keeps listening. That’s why your heart rate increases even in sleep.”

Noise is unwanted sound. It comes from traffic, trains, airplanes and sometimes even from the things we associate with joy. One person’s fun celebration is another’s sleep-depriving nightmare.

In Barcelona’s historic Vila de Gràcia, I meet Coco, who lives in a charming old building nestled in a neighborhood full of character. From her balcony, you can see the famous Sagrada Familia. Neighbors gift each other food fresh limes, homemade tortillas, pastries. It’s a close-knit community.

But there’s a cost.

“It’s noisy here. Twenty-four hours a day,” Coco tells me. “Dogs bark all night, parties go on until morning, and the courtyard is always loud.”

She plays a recording on her phone music so loud it shakes the windows. Her home, meant to be a sanctuary, has become a source of despair. “It brings frustration. It makes me want to cry,” she says.

She believes the constant noise is impacting her health. “I’ve been hospitalized twice for chest pain. I feel it in my body. It changes how I feel, inside.”

According to Dr. Maria Forster, who studies noise for the World Health Organization, traffic noise causes 300 heart attacks and 30 deaths per year in Barcelona alone. And across Europe, noise contributes to an estimated 12,000 premature deaths annually, disrupts sleep for millions, and impacts mental health.

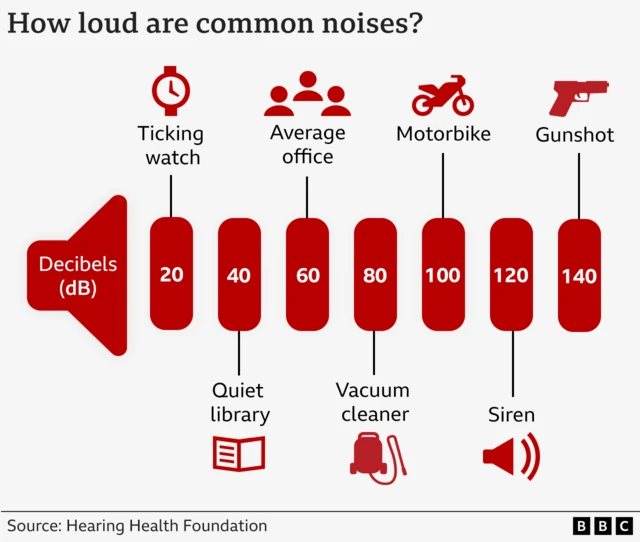

At a quiet restaurant near one of Barcelona’s busiest roads, Dr. Forster shows me her sound meter. Even here, the background traffic registers just over 60 decibels. We could speak comfortably but that’s still enough to cause harm.

“The maximum safe daytime noise level for heart health is 53 decibels,” she explains. “Anything more increases health risks.”

And at night? We need even quieter surroundings. “We need more silence to sleep properly,” she adds.

But it’s not just the volume it’s how disturbing the noise is. Whether we feel in control of it also affects our body’s response. The more helpless we feel, the more stress it causes.

Dr. Forster likens the effects of noise to air pollution both are harmful, but noise is harder to see and understand. “We know chemicals are bad. But understanding that sound a tangible, everyday thing can affect our health in the same way isn’t intuitive.”

Even joyful events like parties or parades can be disruptive to others. Traffic, however, remains the main source of harmful noise exposure and it’s practically unavoidable. It’s around us when we commute, shop, take kids to school. Escaping it means changing your entire lifestyle.

To see what change could look like, I take a walk through the city with Dr. Natalie Muller from the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. We start on a noisy main road my sound meter reads over 80 decibels. As we turn into a quiet, pedestrian-friendly avenue, the number drops to just above 50.

The difference is immediate.

This street is part of a new urban design model where entire blocks have been cleared of through traffic. There are restaurants, benches, and shaded walkways. The city originally planned to build more than 500 “superblocks” like this, but only six have been completed.

Dr. Muller believes the project’s potential is enormous. She estimates the initiative could reduce city-wide noise pollution by 5% to 10% and prevent 150 premature deaths every year due to noise-related health effects. And that, she says, is “just the tip of the iceberg.”

Unfortunately, the plan stalled. The city council declined to comment.

As urbanization grows, so does the problem. In Dhaka, one of the world’s fastest-growing cities, traffic congestion and constant honking have made it the noisiest city on Earth.

That’s why artist Mominur Rahman Royal stages silent protests in the city’s busiest intersections. Holding a large yellow sign, he urges drivers to stop honking. His motivation? The birth of his daughter.

“Birds, rivers, trees they don’t make any sound unless humans disturb them,” he says. “People are the problem.”

Even government officials are starting to take notice. Syeda Rizwana Hassan, an environmental advisor in Bangladesh, admits she’s “deeply concerned” about noise-related health risks. Campaigns are underway to reduce honking and raise awareness, but progress will be slow.

“It can’t be done in a year or two,” she says. “But when people begin to feel the benefits of less noise, their habits will change.”

Still, tackling noise pollution remains one of the most difficult and complex public health challenges. Solutions often require a total rethink of how we design our cities, our homes, and even our celebrations.

As Dr. Masrur Abdula Qadir of Bangladesh Professional University puts it, “Noise is a silent killer and a very slow one.”

That’s why, after all this, I’m left with one lasting thought: the greatest luxury in the modern world may be silence. And maybe, just maybe, we should fight harder to preserve it.

SOURCE :- BBC SINHALA