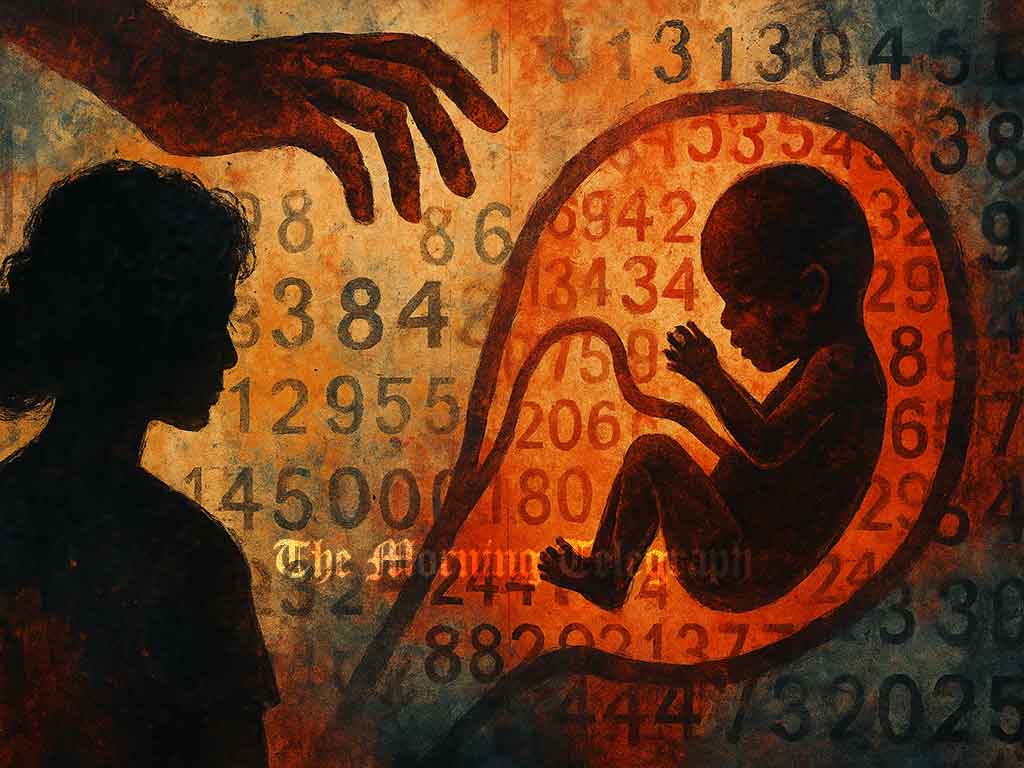

Politicians love a crisis, especially when it’s about birthrates. Whether there are too many babies or not enough, the answer is always the same: police women’s choices. In Sri Lanka and beyond, population panic is dressed up as policy, while reproductive freedom quietly slips away.

Across the world, demographic debates are being churned out with alarming speed. Europe and East Asia cry over declining fertility, Africa and South Asia get labeled overpopulated, and Sri Lanka stands at the messy intersection where panic over numbers trumps any respect for reproductive autonomy. Leaders aren’t asking how people live, but how many people can be counted, making panic itself the policy.

The World Bank reports Sri Lanka’s fertility rate has crashed from over 5.0 in the 1960s to 1.9 in 2021, dipping below replacement level. The UNFPA has paired this decline with warnings about a rapidly aging population: by 2041, one in four Sri Lankans will be over 60. Meanwhile, record-breaking outmigration adds another twist. Over 300,000 citizens left for foreign work in 2022, the highest ever, and 144,000 have already left in 2025. Instead of addressing why so many flee, policymakers clutch their pearls over falling birthrates and fuel a new wave of “population panic.”

But here lies the danger: panic politics invite governments directly into the private world of family life. Across Europe, Hungary and Poland dangle housing allowances, childcare perks, and cash rewards to coax bigger families, while critics point out these policies shove women back into traditional caregiving roles and set back gender equality. At the other end, China’s notorious one-child policy left a trail of coercion, forced abortions, sex-selective practices, and warped gender ratios. Sri Lanka’s record is no less complicated. International agencies once praised its mid-20th century family planning programs, but hidden beneath the success stories were allegations of coercion—especially targeting estate women pressured into long-term contraception. More recently, the 2022 economic crisis exposed just how fragile reproductive access is, as shortages of healthcare hit rural and poor women hardest.

Globally, the story repeats. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs ruling overturned Roe v. Wade, demolishing federal abortion protections and sparking furious fights over women’s bodies. In China, after decades of restricting births, the government now scrambles to push women into having more children, while still imposing limits on reproductive freedom. No matter the continent, the pattern is clear: women’s bodies become demographic battlegrounds, treated as state assets rather than autonomous beings.

South Asia reflects this tension acutely. In Sri Lanka, abortion remains legal only to save a woman’s life, with every attempt to expand access drowned out by cultural and religious battles. When population unease rises, abortion laws get stricter, reducing women to vessels of “national survival.” Migration sharpens the problem, as women working abroad often in domestic labor lose both reproductive autonomy and social protection, leaving their bodies controlled by circumstance and policy alike.

Economic realities only add fuel. Unemployment pushes youth to seek work abroad, leaving family formation clouded by doubt. In 2022 alone, 311,000 Sri Lankans left the country for jobs overseas, a record high, with 144,000 more already gone in 2025, according to the Bureau of Foreign Employment. Migration reshapes family choices, yet governments still obsess over womb counts instead of fixing structural failures.

Meanwhile, panic politics deepen inequalities. Coercive fertility drives or incentives rarely empower; they usually target the marginalized and impoverished. Instead of improving childcare, healthcare, or economic security, the state pushes women into roles that serve demographic goals, not personal dignity. Feminist critics argue that real reproductive justice means not just the right to avoid pregnancy, but the right to raise children in safe, supportive conditions.

For Sri Lanka, the path forward cannot be fear-driven. It must mean rebuilding healthcare, strengthening reproductive services, and addressing disparities in rural and estate communities. Empowerment, not coercion, should be the compass. Whether the threat is of too many or too few, policy must respect the fact that reproductive decisions belong to individuals not governments.

In the end, the issue is not whether Sri Lanka’s fertility rate is below replacement. Numbers will rise and fall, but human rights should never be collateral damage. The true test for Sri Lanka, and for all societies facing demographic change, is whether dignity and freedom remain central. If fear-forged narratives continue to justify restrictions on choice, reproductive autonomy will erode further and democracy will crumble with it.