Al Jazeera’s ‘Head to Head’ program featuring former President and six-time Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Ranil Wickremesinghe, was broadcast last week. During the program, Wickremesinghe was questioned based on the report of the Presidential Commission, also known as the ‘Batalanda Commission,’ regarding the “Batalanda Torture Chamber.” The answers he provided have attracted close attention in society.

Meanwhile, the report of the Batalanda Commission, which has not yet been presented to Parliament, is expected to be tabled this week. Cabinet Spokesperson Nalinda Jayatissa confirmed this in response to a question posed by a journalist at the Cabinet Decisions Information Press Conference held today (March 11).

He stated that during the cabinet meeting held on March 10, it was decided to present the report to Parliament this week.

Accordingly, the questions many people are asking are: What is the Batalanda torture chamber? What is the relationship between the Batalanda Commission report and Ranil Wickremesinghe? What did witnesses testify before the commission? Below is an investigation conducted by BBC Sinhala.

Background

The Batalanda torture chamber is a site associated with allegations of extrajudicial killings, cruel torture, and illegal detentions committed by the then-government in the late 1980s.

The Presidential Commission, appointed by former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, revealed that various individuals were abducted, killed illegally, and tortured in connection with the Batalanda housing project during the period 1988–1990, with the involvement of police officers.

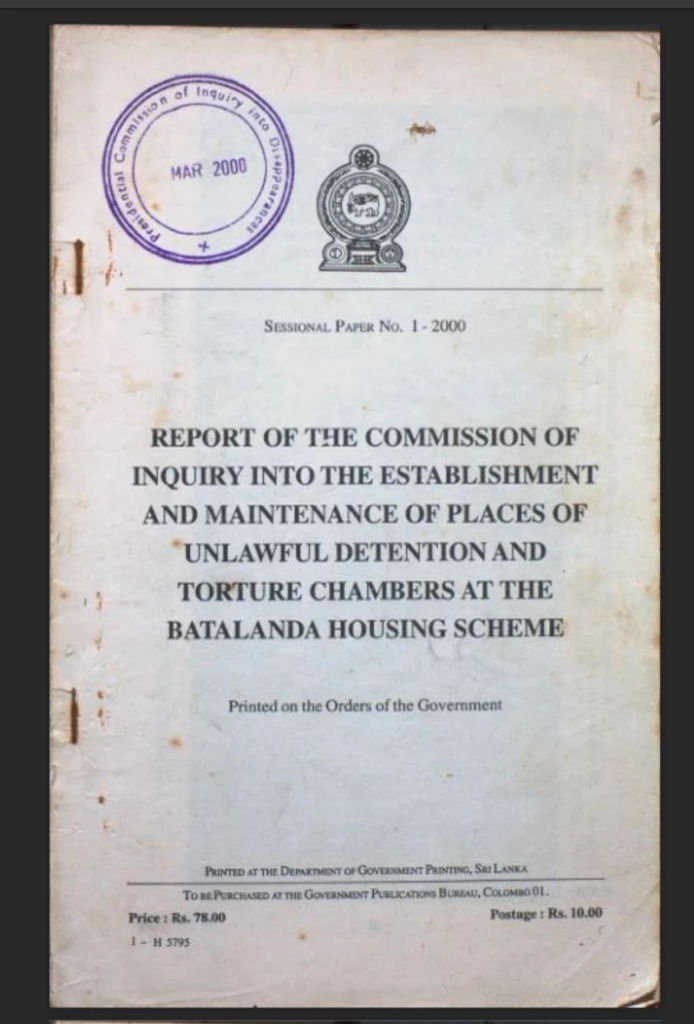

What is the Batalanda Report?

One of the main election promises of former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga, who came to power in 1994 with the slogan “Against Corruption and Terror,” ending 17 years of UNP rule, was to deliver justice for the alleged torture and killings committed by the then-UNP government.

Accordingly, significant attention was paid to the Batalanda torture chamber and related incidents at the time.

Shortly after assuming office, a Presidential Commission was established under the powers vested in the office of the President to investigate the incidents that occurred at the Batalanda torture camp and the surrounding area.

Although the commission was initially instructed to submit its report by September 20, 1995, the process was delayed approximately twelve times, and the report was finally submitted to the former President on May 5, 1998.

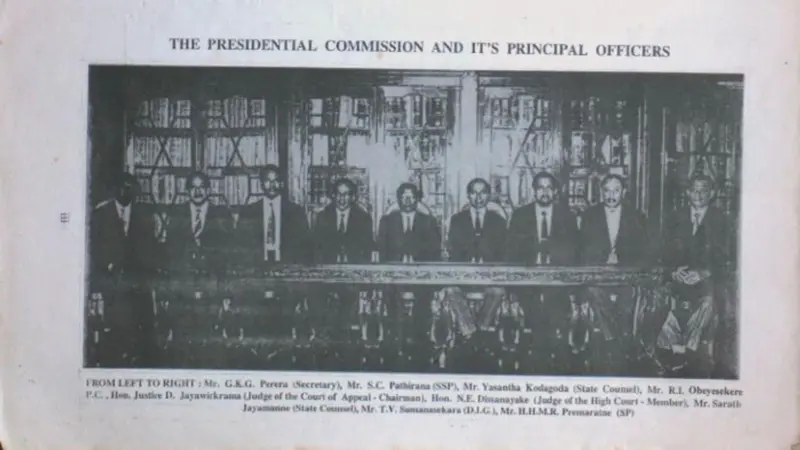

Attorney-at-Law S. Gunawardena, a former officer of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service, served as the Secretary of the Commission for some time. After his resignation, David Geeganage, the Assistant Secretary of the Commission, acted as the Secretary. Later, G. K. G. Perera, an officer of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service, Class II, Grade I, served as the Secretary of the Commission.

Other members of the commission included Senior Superintendent of Police S. C. Pathirana, then-State Counsel Yasantha Kodagoda, President’s Counsel R. I. Obeysekara, Court of Appeal Judge D. Jayawickrama, High Court Judge N. E. Dissanayake, State Counsel Sarath Jayamanne, Deputy Inspector General of Police T. V. Sumanasekara, Superintendent of Police H. H. M. R. Premaratne, and a group of other officials.

However, it is noteworthy that this report has not yet been presented to Parliament.

The commission’s mandate was to investigate five matters, including whether the then-government illegally detained and subjected individuals to inhuman torture at the Batalanda housing complex belonging to the State Fertilizer Company from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 1990, and who was responsible for these acts.

The commission held 127 days of public hearings starting from January 16, 1996, with all meetings convened in High Court No. 2 of the High Court Complex in Colombo.

A total of 82 witnesses were questioned by the commission, including prominent figures from the previous United National Party (UNP) such as Ranil Wickremesinghe, Joseph Michael Perera, and John Amaratunga.

The commission’s written reports span 28 volumes and consist of 6,780 pages.

Batalanda and Ranil Wickremesinghe

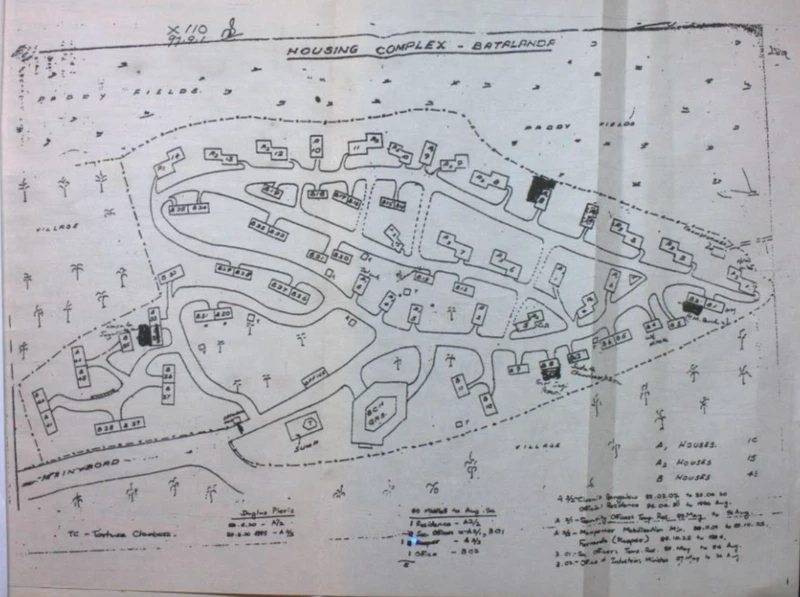

The Batalanda Housing Complex, owned by the State Fertilizer Corporation, was built in the middle of Batalanda village in the Biyagama electorate of the Gampaha District. The complex consisted of 64 housing units, categorized as A, B, and C based on their size and amenities.

According to the Commission’s report, the then Minister of Industries, Ranil Wickremesinghe, contacted Asoka Senanayake, the liquidator of the State Fertilizer Production Company at the time, and requested that several houses in the Batalanda Housing Complex be allocated to police officers.

The officer who took control of these houses through the Fertilizer Corporation was identified as Douglas Peiris, an Assistant Superintendent of Police.

Asoka Senanayake testified before the Commission that the provision of houses in the Batalanda Housing Complex to police officers was carried out solely on the instructions of Ranil Wickremesinghe. He further stated that he would not have allocated the houses to police officers if Wickremesinghe had not issued such instructions.

Additionally, the Commission noted that no formal agreement was signed regarding the allocation of these houses. Ernest Perera, a then Politburo member, testified before the Commission that the entire arrangement appeared to be a “private transaction” between Mr. Douglas Peiris, the officers of the corporation, and the relevant minister.

House A 2/2 in this housing complex was used as Ranil Wickremesinghe’s tourist bungalow from March 2, 1983, to August 1994, during his tenure as the Minister of Youth Affairs and Employment. Later, it was also used as his official residence while serving as the Minister of Industries.

The Commission’s report states that several houses in the Batalanda Housing Complex were used for illegal detention and torture. As detailed in the English report (pages 23–26), the house numbers, their purposes, and the individuals associated with them are listed as follows:

Houses Identified for Illegal Detention & Torture

- B 2: Used as Ranil Wickremesinghe’s office from 1989 to August 1994.

- T. M. Bandula, testifying before the Commission, stated that he was forcibly detained in this house. He later identified the house when the Commission conducted an inspection of the housing complex.

- B 1: Occupied by security officers assigned to Ranil Wickremesinghe.

- B 7: Occupied by Ranil Wickremesinghe’s personal security officer, Police Inspector Sudath Chandrasekara.

- B 8: Occupied by security officers of Assistant Superintendent of Police Douglas Peiris.

- Witness Earl Sugee Perera identified this house as the location where he was forcibly detained and tortured.

- House B 8 was situated near House B 7 and directly opposite House A 2/5, where Assistant Superintendent of Police Douglas Peiris was reported to have stayed.

- On May 24, 1996, when the Commission inspected the housing complex, it was observed that “Black Cats” had been painted on a glass window of this house.

- B 34:Handed over to the Sapugaskanda Police.

- Wasala Jayasekara testified that he was forcibly detained in this house.

- A 1/8: This house was not officially allocated to anyone, but police officers were frequently present in the vicinity.

- The liquidator of the Fertilizer Corporation informed the Peliyagoda Police and Ranil Wickremesinghe about this situation, yet no action was taken.

- Ajith Jayasekara testified before the Commission that House A 1/8, located next to House A 1/7, where Ranil Wickremesinghe’s security guards were stationed, was used as a detention center where individuals were forcibly held.

Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Testimony

The Commission questioned former Minister of Industries, Ranil Wickremesinghe, regarding these allegations. In his testimony, he stated that the allocation of houses in the Batalanda Housing Scheme had been carried out at the request of former Minister of Defense, Ranjan Wijeratne, who was later assassinated.

However, Wickremesinghe failed to present any valid written documentation to support this claim. The Commission rejected his statement, as neither the then IGP nor the Police Headquarters had any knowledge of such a request, according to the report.

During the proceedings, the Commission informed Ranil Wickremesinghe that a witness, T. M. Bandula, had testified that he was detained and tortured in House B 2. In response, Wickremesinghe stated that if such an incident had occurred, he would have been aware of it since he used the house for various purposes.

After reviewing the evidence and other relevant factors, the Commission accepted Bandula’s testimony as conclusive. As a result, the report states that “the inevitable conclusion is that Mr. Wickremesinghe was aware (at least) that House B 2 was being used for the above-mentioned illegal activities.”

Furthermore, the report suggests that Wickremesinghe could not have been unaware of the activities that took place in House B 2, as well as in House B 8.

Meetings Held in Batalanda

During the Commission’s trial, Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) Nalin Delgoda, the most senior officer in the Kelaniya Police Division, stated during questioning by the State Counsel that certain meetings had been held at the Batalanda Housing Scheme and were chaired by Ranil Wickremesinghe. However, Wickremesinghe was not the Minister of Defence or the State Minister of Defence at the time but was serving as the Minister of Industries.

SSP Delgoda admitted to attending several of these meetings. Initially, he stated that they had been held at House A 2/2, which was Ranil Wickremesinghe’s official tourist bungalow. However, he later testified that the meetings had actually been held in a house opposite the bungalow.

Under questioning, Delgoda stated that these meetings, chaired by Ranil Wickremesinghe, were held with the aim of “maintaining law and order.” However, he later admitted that the discussions included “what kind of action should be taken to suppress the saboteurs.”

The Commission questioned SSP Nalin Delgoda regarding the necessity for Ranil Wickremesinghe to chair these meetings. In response, Delgoda stated that Wickremesinghe provided “political leadership” to the police officers. When asked why the police officers required such political leadership, Delgoda replied, “I had no other option in this matter except to follow political orders.”

The Commission’s report states that Meril Gunaratne, who was a Deputy Police Chief at the time, along with other senior police officers, participated in these meetings. Since House B 2, where several meetings were held, was also identified as a location where people were tortured, the Commission concluded that those who attended these meetings could not have been unaware of the illegal activities taking place there.

According to the Commission’s report, Ranil Wickremesinghe failed to present any government decision authorizing these meetings during questioning.

Additionally, the lack of official records or notes from these meetings led the Commission to determine that they were not formal meetings.

For these reasons, the report concludes that “the matters discussed in Batalanda were illegal.”

Death of Attorney-at-Law Wijayadasa Liyanarachchi

Attorney-at-Law Wijayadasa Liyanarachchi disappeared on or around August 25, 1988.

President’s Counsel Ranjith Abeysuriya lodged a police complaint regarding his disappearance.

At the time, the then Defense Secretary asked the then IGP, Ernest Perera, whether Liyanarachchi had been arrested. The IGP then inquired with the DIG in charge of Colombo, who stated that no such arrest had taken place.

According to the report, Ravi Jayawardena, son of former President J. R. Jayawardena and an advisor to the Ministry of State Security at the time, suggested to the IGP that Attorney-at-Law Wijayadasa Liyanarachchi may have been arrested by the Tangalle Police.

Later, when the IGP inquired with the Superintendent of Police of the Tangalle Police Division, Karavitage Dharmadasa, the officer admitted that Liyanarachchi had indeed been arrested.

As stated on page 72 of the Commission’s English report, according to the testimony of former IGP Ernest Perera, Ranil Wickremesinghe telephoned him at around 12 noon on August 31, 1988, and informed him that he “expected” the IGP to take steps to bring the suspect [Attorney Liyanarachchi] to Colombo and hand him over to the “special team operating in the Kelani Division.”

Following this, Attorney Liyanarachchi was brought to Colombo under the IGP’s instructions and was received on September 1 by Inspector Kularatne of the Kelani Area Anti-Subversion Unit.

On September 2, at around 12 noon, Liyanarachchi was admitted to the Colombo General Hospital with severe injuries. At approximately 11:00 AM, his condition worsened, and he passed away about half an hour after midnight.

According to the report, the post-mortem examination determined that the cause of death was “assault with blunt weapons,” and a total of 207 injuries were found on his body.

During the Commission’s questioning, Ranil Wickremesinghe denied having instructed the IGP over the phone to bring Liyanarachchi to Colombo.

He stated that it was, in fact, the IGP who had called him, asking whether he objected to sending Liyanarachchi from Tangalle to Colombo and detaining him at Sapugaskanda Police Station.

A key detail highlighted in the report is that while Ranil Wickremesinghe denied giving such instructions to the IGP, his lawyer did not cross-examine former IGP Ernest Perera on this matter during the hearings.

Who is Responsible According to the Batalanda Commission Report?

If any person or persons were detained in the Batalanda Housing Scheme between January 1, 1988, and December 31, 1990, and were subjected to inhumane and degrading treatment, those who are directly and indirectly responsible are listed in the English report of the Batalanda Commission, specifically on pages 119 to 122, as follows:

On several occasions since 1986, the then Minister of Industries, Ranil Wickremesinghe, had ordered the authorities of the Fertilizer Company to provide houses to police officers in the Batalanda Housing Scheme. Assistant Superintendent of Police Douglas Peiris was responsible for obtaining up to 13 of those houses through him. Ranil Wickremesinghe’s order to allocate houses in this manner was deemed an abuse of ministerial power.

Senior Superintendent of Police Nalin Delgoda was responsible for failing to take action despite knowing that acquiring these houses violated Police Department regulations. If any illegal activities took place in these houses, he deliberately refrained from stopping them.

Ranil Wickremesinghe misused his power by calling meetings involving police officers within the Batalanda Housing Scheme, which he chaired. Furthermore, he interfered in police duties and law enforcement activities.

The houses allocated at Ranil Wickremesinghe’s request were used to establish illegal detention centers.

Ranil Wickremesinghe and SSP Nalin Delgoda are directly responsible for operating illegal detention centers and torture chambers in houses B 2, B 8, B 34, and A 1/8 of the Batalanda Housing Scheme.

Additionally, the report states that the then DIG M. M. R. (Merrill) Gunaratne and the then IGP Ernest Perera were responsible for failing to take appropriate action despite having knowledge of these illegal activities.

What Are the Recommendations of the Commission?

One of the main recommendations of the Presidential Commission Report is to delegate jurisdiction to the Supreme Court to impose appropriate penalties, including the deprivation of civil rights, on individuals found to have repeatedly violated the fundamental rights of citizens.

This is detailed on pages 124 and 125 of the Commission’s English report.

The report highlights that certain executive officials have continuously violated fundamental rights because they were not promptly or appropriately punished for their actions.

Additionally, it recommends the appointment of a committee to amend the Criminal Procedure Code, granting relevant courts the authority to investigate illegal activities at locations where such acts are taking place.

Since police officers themselves were often responsible for these crimes, this recommendation aims to prevent fear among those who wish to report such illegal acts.

Moreover, the report includes several other recommendations, including a directive for the Inspector General of Police (IGP) to conduct investigations into all complaints received by the Commission.

SOURCE :- BBC SINHALA